The crowning glory of Victorian womanhood; Or was long hair a huge time-waster instead?

Until the decade from 1910 to 1920, it was unthinkable that American women would wear their hair cut short. Nor was it at all proper for women to go out in public without wearing a hat. Styles in millinery accommodated whatever the hair styles dictated.

Long hair

Females could wear their hair “down” in polite society until around the age of 16. After marriage, women had no choice but to wear their hair “up,” in complicated “dressings” or with a simple center part and the rest gathered into a bun or a fancier chignon at the back. Hats were perched high on the head, or even tilted forward to accommodate the volume of hair at the back.

“Letting her hair down” is an idiom today for getting relaxed, as opposed to being “up tight.” In Victorian times it wasn’t just an idiom, it was an act that only occurred in the bedroom when a woman took the hairpins out and brushed her long hair. Only her husband (or her maid) could see her that way, though the romantic notion of flowing tresses implying femininity was depicted in paintings and advertising—beautiful women with impossibly abundant hair.

The website www.whizzpast.com/victorian-hairstyles-a-short-history-in-photos has many images showing Victorian women in intimate moments with their hair down. It also shows elaborate updo’s that were stylish, though very difficult to emulate.

The bun was something that any woman could do for herself, with the aid of a number of hairpins. But the more elaborate styles required assistance, and that became the problem for women of Laramie as elsewhere. As the Downton Abby TV series showed, a proper ladies’ maid of the Victorian era had to be skilled in hair dressing. But Laramie women tended to employ “kitchen maids” who had no such skills, if they employed a maid at all.

Visiting hair dressers

From 1868 until around 1910, there were no beauty salons in Laramie. In the March 14, 1871 issue of the Laramie Daily Independent there is a note that “Madame Croze of France” would arrive from Denver for a one week stay at Mrs. Hatcher’s dress and millinery house on Second St. The close relationship of hats to the hairdo made this a respectable place for women to visit.

As late as June 10, 1909, the Boomerang reported that “Mrs. M.R. Clippinger announces that she has secured the services of an expert hair dresser from Denver and will be pleased to make appointments during commencement week.“ It was common for a traveling hair dresser to arrive in advance of a major social event to fix women’s hair.

Barbers before 1900 sometimes called themselves “hair dressers,” but that was not because they had women as customers. Rather, it was for the purpose of styling men’s hair to cover a bald spot or to create finger waves that were coaxed into place with sticky “Macassar” oil, a men’s tonic to make the hair glossy and manageable. The dark oil also left stains on the back of upholstered chairs men sat in. Housewives dealt with that problem by crocheting “antimacassars,” washable doilies that were pinned to the back of chairs.

Hairpieces

A solution to the hair dilemma for Laramie women could involve purchasing hairpieces, extensions already formed into ringlets and curls that could be attached or even tied onto the head to give the effect of the latest style. As early as 1874 the Sentinel newspaper mentions that these extensions were available in Laramie stores.

Most hairpieces were human hair, said to be from French or Italian nunneries where novitiates were required to have their hair shorn before they entered the final stages of the religious order—symbolizing their abandonment of personal vanity. However, selling one’s hair was an option for impoverished women anywhere, as attested by “The Gift of the Magi,” a short story by novelist William Sydney Porter, who used the pen name “O. Henry.” It was first published in 1905 and features a young bride who sells her hair to buy a fancy watch fob for her husband.

In the Boomerang of March 1, 1904, a news story estimates that “100 tons of human hair, valued at $3 million,” has been received at the New York port this year. That story also revealed that women were losing their disdain for having men style their hair. By 1904, the extremely intricate updo’s of the Victorian age were giving way to the loose “pompadour” style of the Gibson Girl, made popular by the illustrations of Charles Dana Gibson.

This style of the early 1900s involved pulling the hair up loosely over circular “rats” of human hair and completely covering it with the wearer’s own hair. Tendrils of hair often escaped the wrapping and fell down along the neck or cheek, which was considered very alluring. Again, it was a style that was much easier for Dana to draw than for women to emulate. However, persistence paid off, as photos of the era show that many women did manage to achieve the look.

Sometimes the “rat” was made out of a woman’s own hair, saved from her brush and placed into a dressing table china dish called a “hair receiver.” The lid of the dish had a finger hole in the center through which the tangled “rat” of hair from a brush could be pushed. This had the advantage of being the same color as her natural hair, unlike purchased rats.

Hair ornaments

The secret to holding the updo’s in place was usually hairpins, not to be confused with “bobby pins” that came later. Hairpins were thin, u-shaped, flexible crimped wire that could hold hair if enough were used.

While the hairpins were meant to be hidden, there were decorative “combs” that had long teeth, usually of tortoise shell. They had a decorative band at the top that could be very large and covered with jewels or elaborate carving.

Other hair ornaments like coronets, feathers, scarves or metal bands could also be entwined into the hair adding further glitter and securing some of the hairpieces. Their popularity is attested by the fact that over 150 originals and reproductions of Victorian hair combs are for sale now on eBay, at prices from $1 to $250 each.

Hair washing

Before 1920, women washed their hair at home and allowed most of the day to let to let their long hair dry.

There are no ads in Laramie newspapers for commercial shampoo products until around 1900. But there are a number of stories published with advice. One, from an 1891 issue of the Boomerang, says the best thing for washing the hair is hard kitchen soap, rubbed on quickly and washed off, concluding: “Soap suds thickened with glycerin and the white of an egg are responsible for the lovely satiny gloss.”

Another Boomerang article from December of 1894 claims that excessive shampooing creates dandruff and advocates only one wash in two or three weeks, followed by “a mixture of soft soap and petroleum [Vaseline?] to give the hair a beautiful gloss.” It also says: “Much cutting of the hair causes early grayness.” Obviously, there were a lot of poorly understood things about the hair and scalp in the Victorian age.

There is an amusing blog post from 2016 by Melodi Erdogan on the website “bustle.com” titled “I Washed My Hair With Mayo & This Is How It Went.” She was following another old “tip” for glossy hair passed down in my family. Erdogan overdid it with the mayo and missed the other family tip, which was a rinse with lemon juice afterward.

Victorian women went to a hair dresser to have their clean hair styled, not to get it washed. “There was a time when washing your hair was seen as a perfectly acceptable excuse to decline an invitation out. It wasn’t so much the washing . . . but the drying” says the blogger “Veronica” in a 2017 online post called “The History of the Hair Dryer.”

Several sources credit the invention of the hair dryer to the Frenchman Alexander F. “Beau” Godefroy in 1890. His was a stationary model, powered by a gas furnace. By the 1920s electric hair dryers were available in America. They were low wattage and heavy, so they took a long time to dry, and usually involved a bubble-like bonnet that fit over the head, with the motor and fan stationed behind the user. The pistol-shaped hand-held dryer came about later, becoming much lighter after plastics were invented.

“Microbes”

A quack medicine promotor noticed the mismatch between luxurious long hair that Victorian women desired, and the limp, thin thatch that many women regretted. He came up with “scientific” findings that all hair and scalp problems were due to a minuscule microbe that was eating at and destroying hair follicles, forming dandruff and “starving” the hair and causing it to fall out. Thus the hair follicles needed to be “fed.”

This concoction, called Newbro’s Herpicide, was invented by Dupont M. Newbro, a druggist from Butte, Montana. He moved to Detroit to market his “herpicide,” an invented word that essentially means “kills creepy things.” His marketing plan was genius, involving extensive advertising and using many of the same bogus claims that were rampant in the patent medicine business. They include “personal testimony” claims from unknown or non-existent people, “guaranteed” solutions or your money back (but never saying how long a cure would take), and doctored photos of supposed product devotees.

Newbro’s Herpicide would kill microbes, the ads claimed, perhaps with the addition of oils to “feed” the hair follicles. The oils could make the hair sticky and dull, so users were admonished to only rub it into the scalp, not into the hair itself. The Newbro product was advertised hundreds of times in Laramie newspapers between 1900 and 1913 but continued to be produced through the 1930s. In 1922, prohibition agents in Nebraska nabbed a huge shipment of illegal alcohol destined for Newbro, thus disclosing the main ingredient.

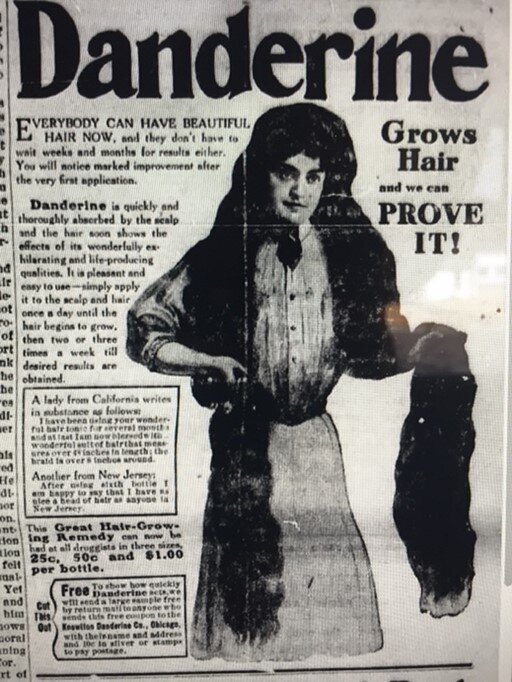

The makers of a competing product called “Danderine” didn’t go in for the subterfuge of “microbes” but did vow: “stops falling hair and destroys dandruff.” It too was advertised often in Laramie newspapers, usually with a photograph of a woman with long hair to her knees, though modestly dressed, unlike the trade cards common at the time, picturing models with long hair twisted seductively about themselves.

Scissors arrive!

In the 1920s, the change in attitudes about the place of women brought to a close the image of the helpless female, trapped by her own hair and spending hours tending to it.

Singer Mary Garden said in 1927: “I consider getting rid of our long hair one of the many little shackles that women have cast aside in their passage to freedom. . . to my way of thinking, long hair belongs to the age of general feminine helplessness. Bobbed hair belongs to the age of freedom, frankness, and progressiveness.”

P.S. An unmentionable

Does anyone else remember when grandmothers were horrified that anyone would allow visitors’ coats and hats to be stacked on a bed? Grandma never would have told the reason. It wasn’t a microbe – it was head lice! An insect never to be introduced by accident from a visitor’s hat into clean bedding.

By Judy Knight

Source: www.tumblr.com -- 2013

Caption: Victorian era trade card for French hair perfume and lotion

Caption: Laramie Plains Museum, Daly Collection

Caption: An unknown woman’s studio portrait from a photo album passed down in the Ivinson family. She is wearing an elaborate late 1870s gown with an equally elaborate hairdo, requiring hairpieces to produce. Help would be needed to create this hair dressing and to crown it off with the hair ornament seen at the top.

Source: Boomerang, March 14, 1909, page2

Caption: “Danderine” ad, offering “proof” of effectiveness at growing hair.