Telephone Canyon, new name, old route

Interstate 80 winds its way up and east from Laramie, through a canyon that locals call “Telephone Canyon.” But the canyon was used long before the telephone.

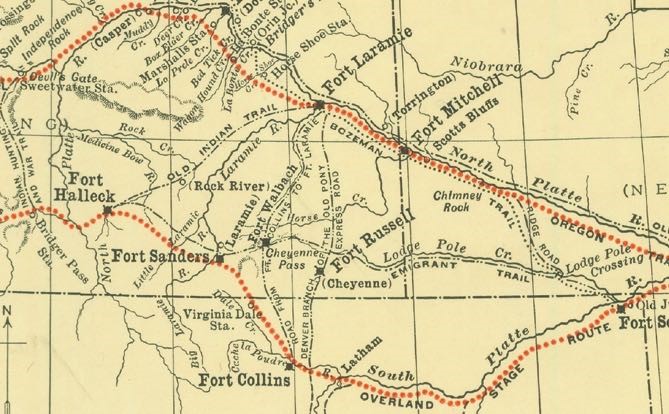

The first name westerners used in this area was called “Cheyenne Pass,” but it is likely further south than what is called Telephone Canyon today. Jim Bridger knew of Cheyenne Pass in 1850 when he guided an expedition through it. Then, the route went fairly straight east from the Summit though what was then called the “Black Hills” instead of bending south to the spot where I-80 reaches Cheyenne today.

The start of this early trail to the Laramie River was Camp Walbach, where the Cheyenne Pass route met a turnoff from the Oregon Trail. “Cheyenne” referred to the Native American Indians, not to the city of Cheyenne, which didn’t exist then.

Camp Walbach was constructed by the military in 1858 to guard Cheyenne Pass and protect emigrants. After a journey south from the Oregon Trail (which did not go through the Laramie Basin) at Camp Walbach some emigrants turned west. It is likely only those on horseback went through Telephone Canyon, whose name at that time is lost. Wagons would have had to go further south and around the canyon on Cheyenne Pass.

When they reached the Laramie Basin, emigrants could pick up what was named the Overland Stage Route. This was a trapper’s route west—in use since the 1820s. By 1858 it came up from what is now Fort Collins to the Laramie River, which it crossed. It was an alternative trail west, roughly 100 miles south of the Oregon Trail, though the two joined in the vicinity of Fort Bridger.

Camp Walbach only existed for seven months before various factors caused it to be abandoned. Bad water was reported for the camp, making people and livestock sick. On top of that, the nearby Canyon was too rugged for wagons, limiting its usefulness.

Though passable by horseback when Laramie was founded in 1868, and possibly passable for those with lots of time to negotiate with their wagons and later vehicles, the canyon trail was not an official auto route until 1919.

When the transcontinental Lincoln Highway was established in 1913, the route from Cheyenne to Laramie followed a graded “road” that the Union Pacific Railroad had built in 1868 and abandoned by 1904. This went southwest from the top and circled around the canyon, coming out at Tie Siding.

Westerners didn’t discover the route that I-80 and the railroad take west from Cheyenne until the mid-1860s. The Cheyenne Pass and Telephone Canyon routes were known and probably surveyed in 1864 but rejected as unsuitable for a railroad, so the chosen railroad route constructed in 1867 went about seven miles out of the way to go around Telephone Canyon, as the railroad still does today.

There are reports that in 1878 telephone wires were connected to the telegraph lines already in place, but that was probably on the railroad line, not in the canyon. The phone lines were constructed in the canyon in 1882, inspiring the new name, “Telephone Canyon.” It is likely that crews erecting the telephone poles did much of the work needed to make the canyon trail accessible by wagons.

Ranch crews used the canyon trail, even for “Telephone Canyon cattle drives” that were mentioned in the newspaper as early as 1886. People from Laramie found the canyon a wonderful place for picnics; there are many newspaper accounts in the late 1880s of outings to Telephone Canyon.

In 1892, a bicycle relay race from Laramie to Cheyenne took place. The “winners” made the trip in “four hours and one minute,” reported the Cheyenne Daily Sun on May 31. But that group of seven winning relay riders made the 57-mile trip via Tie Siding and the old railroad grade skirting the canyon.

A different ambitious bicycle crew of two chose the Telephone Canyon route and for some reason were allowed to begin via a wagon ride up the canyon as far as it could go. But their trip took five hours, six minutes and the man on the last leg into Cheyenne was totally exhausted at the conclusion. (However, the paper claimed the bike riders far outpaced freight trains between Laramie and Cheyenne, which they said took seven hours.)

Once riders got to the top, they could take the Happy Jack trail into Cheyenne. President Teddy Roosevelt rode a train to Laramie on his way back to Washington in 1903, and was delighted by a horseback ride up Telephone Canyon to Cheyenne, 65 miles on the route they took.

The first automobile to go to Cheyenne through Telephone Canyon is not reported—it would have been an arduous ride with many harrowing blind turns on a more circuitous route than the highway takes now. As late as 1914, the UW student newspaper reported that a couple of fraternities rented “from every livery stable in town” to take their lady friends on an excursion up Telephone Canyon—with horses.

Members of civic clubs in Laramie, particularly the Lion’s Club, began agitating for improvements in the Telephone Canyon route to shorten the time to Cheyenne. They called the road “Lion’s Trail,” but that name didn’t stick, though it was used in the newspapers for a short time.

Around 1910 the Albany County Road Superintendent John McCue began preliminary work to develop an auto route in Telephone Canyon. Even the two-mile portion from the mouth of the canyon to the east edge of Laramie had to be straightened and graded because in 1910 few, if any cars went out that way. From 1913 to 1920, the county spent an average of $33,000 per year on road construction and maintenance, with the Telephone Canyon route getting some of that attention.

A film crew creating a publicity movie for the Lincoln Highway Association created a stir by filming in Laramie in the summer of 1915. One of their shots was of a herd of sheep in Telephone Canyon. But that was a teaser; the auto route still went south to Tie Siding.

By 1918 enough improvements had been made that a motorist could actually get to Cheyenne from Laramie using the canyon route. It was beautiful—“when constructed the road will be an unusually good one and also very scenic” said the Boomerang in July of 1918, reporting on the $17,280 the County Commissioners approved to construct a 16 foot wide roadway in the canyon.

Their optimism paid off in 1919 when federal funds with a local county match became available, with most of it earmarked for the Lincoln Highway. By December 1919 the work was done and the Telephone Canyon road was “one of the finest stretches of road along the entire highway between Chicago and Salt Lake City, ” in the opinion of the Laramie Republican newspaper.

In 1919 the Lincoln Highway was moved to Telephone Canyon. It was still a steep grade, and the autos of the day frequently overheated. The Laramie Kiwanis Club created a fountain by piping a mountain spring down to the roadway at a crucial spot where cars frequently needed a rest and water for their overheated engines.

Through at least the 1950s, “Kiwanis Spring” was a welcome rest spot in Telephone Canyon. It is obliterated now by the five-lane superhighway that is beyond the dreams of Road Superintendent McCue in 1910. My only regret is that the only view of Laramie now comes near the bottom of the canyon. When I first saw Laramie at night from what was the summit of US 30 in 1965, its lights really did look like the “Gem City of the Plains” from the top of Telephone Canyon.

By Judy Knight

Caption: Portion of the Oregon Trail and Overland Stage Routes around 1866 by Grace Raymond Hebard and Earl Alonzo Brininstool, drawn for their book The Bozeman Trail. It shows Fort Sanders, which predated Laramie, the route of the Overland trail (bottom red dots) and the Oregon Trail (upper red dots). Cheyenne Pass is marked and the site of Fort Walbach. The full digitized map can be seen in the on-line Hebard Collection at UW. Map courtesy of Grace Raymond Hebard Collection, Emmett D. Chisum Special Collections, University of Wyoming Libraries.