Airmail puts Laramie on the map in the 1920s Pilots hired by the U.S. Postal Service

If it weren’t for hardy left-over planes of World War I and the veterans who flew them, developing coast-to-coast air services might have taken a lot longer to find a place in U.S. transportation history.

But even more important was the interest and investment of the U.S. Postal Service (USPS), beginning in 1918. Until the Post Office got involved, veteran pilots mainly trained other would-be pilots or resorted to stunts and exhibitions at county fairs. “It was a little like a cross between a circus act and a plaything of rich men,” says former Laramie resident and pilot Steve Wolff, of the early barnstormers.

An unlikely sponsor

It was the USPS that got things off the ground after WWI ended. This federal agency saw the potential of using airplanes to shorten the five days that mail by train took to get across the country. In 1918, it had begun experimenting with airmail east of the Mississippi, and had developed an airfield in Chicago.

In January 1920, the USPS announced plans for a coast-to-coast service, following existing routes to Chicago, then railroad tracks from Chicago to Omaha. In Omaha, the Union Pacific Railroad (UPRR) tracks would be used to San Francisco. Flying would be done in daylight hours, as pilots had no navigational devices and had to see landmarks like the tracks, which pilots called their “iron compass.”

Impractical as it seems, the early plan was to put the mail on planes to go as far as they could in daylight, then transferring the mail to UPRR trains to take over for nighttime travel. This proved to shave two full days off the time it took. It was a 20th century Pony Express, without horses.

Semi-reliable planes

The planes used were open cockpit, single pilot, British-designed DeHavilland biplanes. Many were built in the U.S. and over a thousand were shipped to France for wartime use.

Gerald Adams, writing in a 1980 issue of Annals of Wyoming explains that there were plenty of surplus DeHavilland planes available stateside when the war ended. They were reliable enough under 10,000’ elevation and capable of 110 mph. There were two seats, one behind the other; the mail sacks went in the front seat, so no passengers were possible unless the mail sacks were light.

In those early days, forced landings were common, almost to be expected. “Always remember,” said an early pilot’s training guide, “at any given moment the engine could stop.” Rocky Mountain weather provided many challenges, as did the thinner air of higher altitude. Yet the planes and the pilots got through most of the time. It was noteworthy in the Laramie Republican in 1922 that one of the airmail planes had gone over 38,000 miles “with no forced landings.”

The coast-to-coast air mail delivery began on September 9, 1920. In just 9 months, the USPS had purchased planes, hired pilots, leased land and built ground facilities near the railroad tracks. Adams reported that the planes could go 300 miles before refueling, but emergency landing fields 25-30 miles apart were established along with the refueling stations.

Emergency field—Laramie

The route between Cheyenne and Laramie, Adams says, “was considered the worst part of the entire coast-to coast route.” Going over the Laramie Range was treacherous, and the elevation and terrain made establishing an emergency landing field at the preferred interval of 25 miles impossible. If a plane landed, it probably could not have taken off again at that altitude and there was no assistance available.

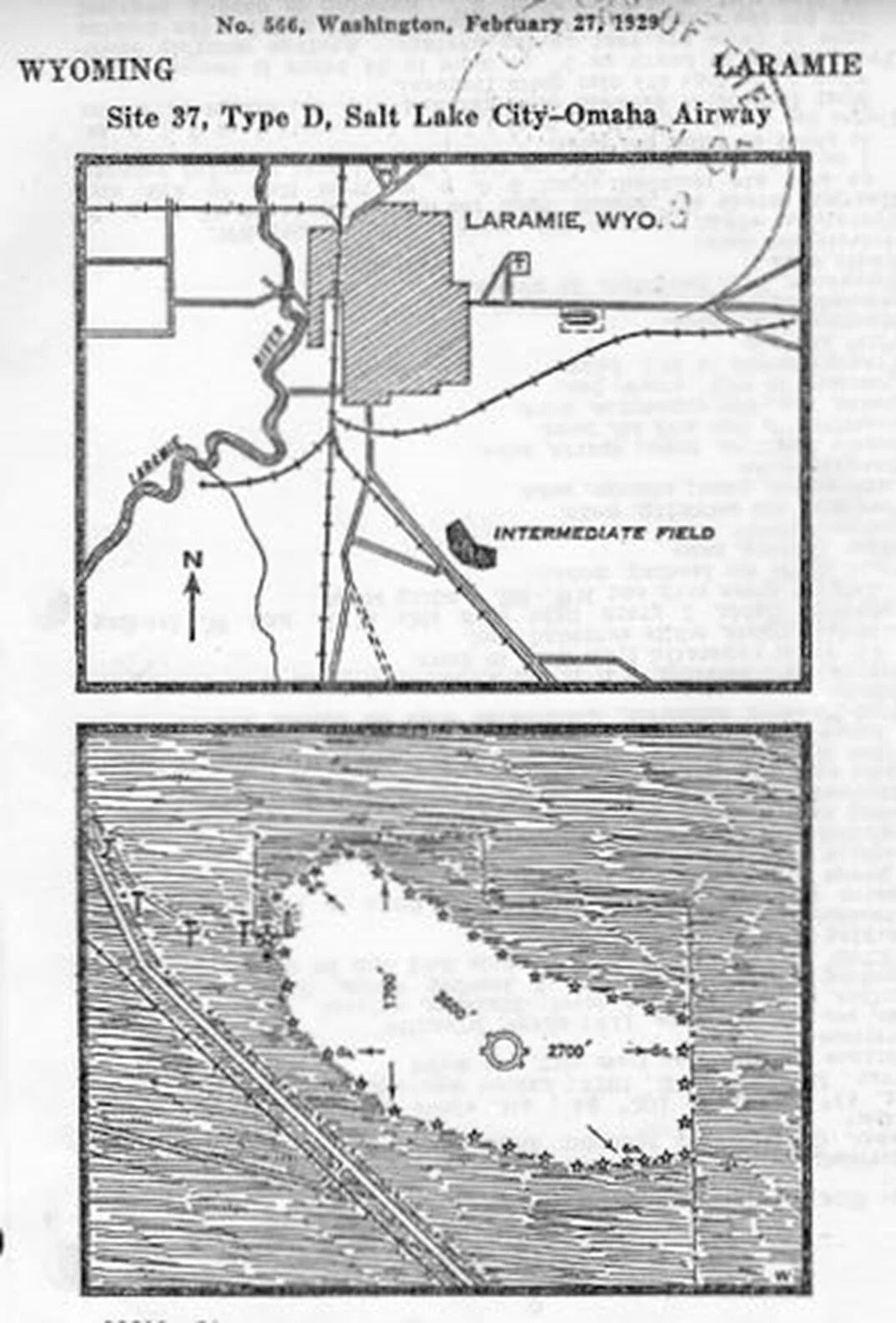

The two emergency landing fields in Laramie became especially important. One shown on a 1924 map was a large empty field east the UW campus starting at 15th St. to 22nd St. and north of Grand Ave. The other was 1.5 miles south of Laramie along Skyline Drive and south to the present Spur Ridge Equestrian Community (east of Soldier Spring Road). However, as Steve Wolff says, “Pilots could land almost anywhere in the Laramie Plains, and did, if they had to. The planes were light, and the tires were fat, like motorcycle tires.”

Neither of the “official” Laramie sites was much more than prairie in 1920, with windsocks probably the only amenities at first. With crashes so common and uncertain weather, the USPS eventually contracted to have some 50 ft. long concrete directional arrows laid out on the ground, with lighted towers placed at most of the landing strips and emergency fields. One such “aeroglyph” still exists where the “Sherman” (actually Pilot Hill) beacon was. Now radio towers are on that site though a portion of the arrow is obscured with a newer building.

First fatal crash

The first fatal crash of an airmail plane happened south of Laramie on November 6, 1920, just two months after the inauguration of the airmail service. Iowa native John P. Woodward crashed his DH-4 in a nose-dive at Red Buttes near Tie Siding. He was three miles east of the UPRR tracks; a snowstorm in the vicinity hampered his visibility. The coroner said he died instantly.

The Laramie Republican published an account of the crash two days later, saying that Woodward was eastbound, and had left Salt Lake City at 11:30 a.m., passing over Laramie in mid-afternoon. The plane was noted by residents because it was flying low on account of the storm, but also because, according to observers, the plane was “wobbling and appeared to be having engine problems.” When he was overdue, the Cheyenne airfield notified local authorities who found the crash site the next evening, on the John A. Stevenson ranch.

Locating the crash site was delayed by snow and the distance from any roads. Finally, Coroner E. W. Johnson made the recovery. He also salvaged the mail. Woodward’s death was one of 34 airmail pilots who died from 1918 through 1927 when the Postal Service’s direct involvement in airmail ended, according to the USPS website.

Night flying initiated

Although many crashes occurred in the daytime, the USPS was undaunted in its conviction that night flying was essential for efficient airmail delivery. In 1921, farmers were asked to light navigational bonfires along part of the Omaha to Salt Lake City route, but that wasn’t practical, and impossible in most of Wyoming. In 1923 the Postal Service began installing navigational rotating beacons on 51 ft. towers on the regular landing fields and on emergency fields, like Laramie’s. A 1929 map of the south Laramie field shows the location of the lighted beacon and other field markings.

A rotating beacon was also placed on top of Pilot Hill where it could be seen from either side of the mountain range, according to Adams. There was no landing strip there, but the beacon, like all the others along the route, still had caretakers. These year-round residents were paid around $1,400 annually and provided with prefabricated housing. Their job was to assure that the gasoline generators and lights were working, and to relay news when a plane passed overhead.

The “Sherman” station was number 38 of 40 between Salt Lake City and Cheyenne. An undated Laramie Republican newspaper clipping written by editor G.A. Cook, who visited sometime in the 1920s contains a long interview with the Sherman caretaker, Mr. F.C. Glascock and his wife. “Mrs. Glascock says she is alone so much of the time during the day that she welcomes an occasional visitor,” Cook wrote, though he also said one of them went to Laramie for supplies every other day. He also notes that the Glascock’s daughter was married to the air station manager in Cheyenne, Mr. H.T. Bean. This clipping was in the Agnes Wright Spring collection at the UW American Heritage Center.

Big change in 1925

All along, funding for airmail was part of the budget for the USPS. Congress was skeptical, but allowed the experiment to continue. After all, nearly 50 years earlier, in 1869, Congress had seen completion of the transcontinental railroad that it had authorized in 1862. In 1925, when the Postal Service proved that transcontinental air transport was possible, Congress passed the Kelly Airmail Act which mandated that commercial contractors gradually take over air operations. This act also included a requirement for passenger service in the airmail planes. An Aeronautics Branch of the U.S. Department of Commerce was established to support the growing industry.

Boeing Air Transport Company of Seattle got the contract for the Chicago to San Francisco airmail route. Boeing’s B-40 planes were designed and put into service on this route in 1927. The 25 planes looked a lot like the DH-4s, bi-planes with open cockpits. The early ones even had the same engines. But redesigned versions had a closed space for what eventually would hold four passengers and up to 1,200 lbs. of mail, though the pilot was still in an open cockpit.

The USPS investment in technology for navigational aids was crucial to developing viable air service in the U.S. It took a while before the commercial carriers totally took over from the USPS; passenger service was slow to catch on. The USPS boasts that “in the days before passenger service, revenue from airmail contracts sustained commercial airlines.”

Rugged individuals

The fascination that the current generation has with unmanned drones doesn’t begin to match the passion that early aviation pioneers had: “rugged individuals who did it for the sheer thrill of it,” says Michael Kassel, Assistant Director of the Cheyenne Frontier Days Old West Museum and author of “Wyoming Airmail Pioneers.”

A whole new world opened up for those with a certain amount of recklessness ready to participate in it. Two such pioneers from Laramie were Fred Wahl (1905-1995) and his student Raymond “Ray” Johnson (1912-1984), both aviators of the second generation who were too young for WWI, but learned from the veteran “aces” and went on to have long aviation careers.

Writer Steve Wolff, who now lives in Lexington, Nebraska, has amassed a collection of memorabilia about the early days of Wyoming aviation with particular emphasis on when things went wrong for pilots. He has compiled a book about notable Wyoming crashes called “Sudden Impact,” which harks back to the days when pilots got disoriented and mountains got in the way.

By Judy Knight

Editor’s Note: . Much of the information in this story comes from the 2013 Wyoming PBS program “Cowboys of the Sky” and from the Annals of Wyoming 1980 article “The Air Age Comes to Wyoming” by Gerald M. Adams. John Waggener of the American Heritage Center located the clipping about the Glascocks. This story and others in the series can be found on the website of the Albany County Historical Society.

Source: Smithsonian National Postage Museum

Caption: 1928 U.S. five-cent airmail stamp showing a navigational beacon light on a 51’ tower. It was supposed to be at Sherman, Wyoming, but according to aviation writer Steve Wolff, the artist actually used a tower from Wahoo, Nebraska as the inspiration and the terrain is imaginary, not like that of Pilot Hill.

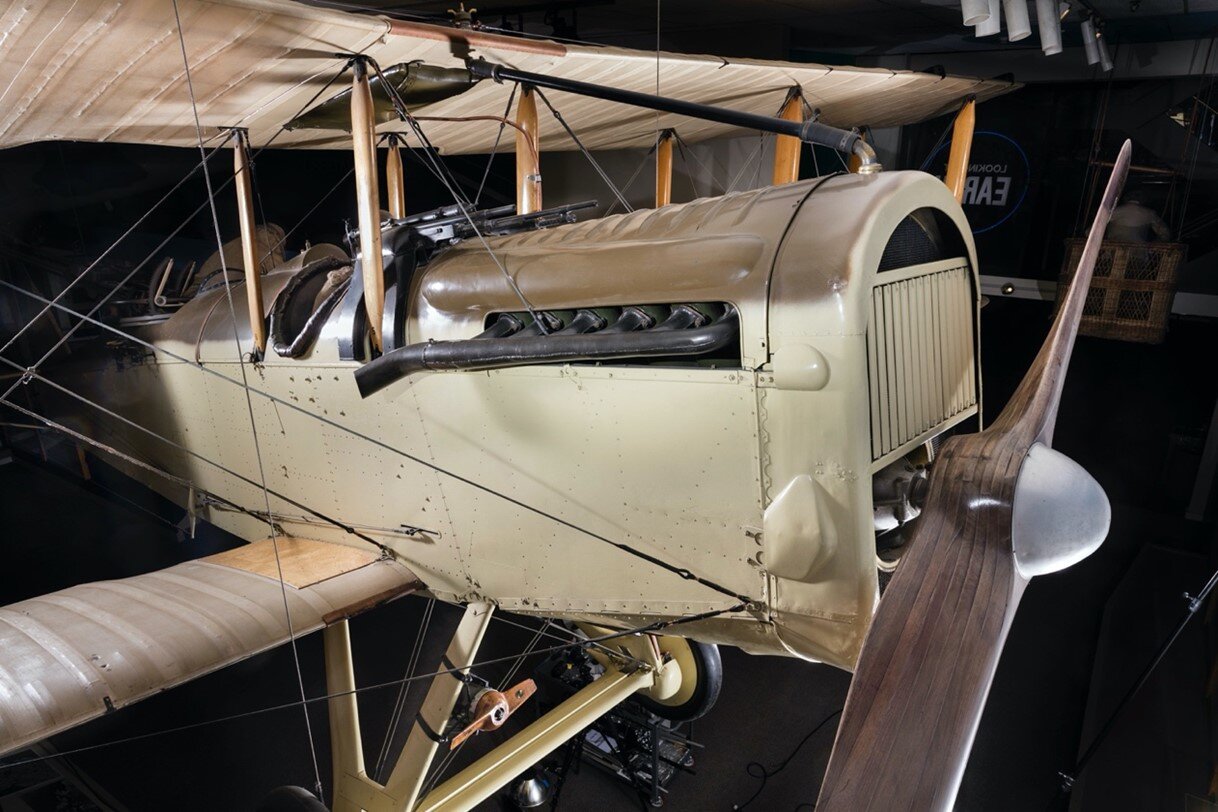

Source: Smithsonian Air and Space Museum

Caption: A De Havilland DH-4 biplane outfitted for WWI use, showing the wooden propellor, engine compartment and the forward seat. For airmail service, the mail was stashed in the front seat, and the pilot was in the back seat. These were the planes that were readily available after hundreds had been made but not delivered in time for wartime service.

Source: US Department of Commerce, Aeronautical Bulletin, 1929

Caption: Emergency (“Intermediate”) landing field on the Salt Lake to Omaha airmail route along what is now Soldier Spring Road and south of Skyline Drive. It was established by the USPS to assist flyers for the first coast to coast airmail flights that began in 1920. The strip was mainly gravel though fairly level, and pilots were told that the entire bean-shaped area 3,600 ‘ long could be used. The Laramie map at the top also shows features recognizable from the air--the railroad spur that went to a quarry east of town, an oval marking the former location of the fairgrounds at 18th St. (now Uniwyo Credit Union building), and a cross for Greenhill Cemetery. South of the cemetery and all the way east to what is now 22nd St. was another emergency landing site, the “Municipal Field.”