A Crazy Idea—In Hindsight

In 1883, would-be developers in Laramie thought they had hit upon a sure thing. They would build a flour mill.

Considering that no wheat was grown in Albany County then, the enterprise seems foolhardy. However, other things made the backers optimistic.

Rosy estimates were that Laramie used 80 carloads of flour each year, so what could be more profitable than a local mill producing that staple for bread? This was at a time when every housewife made as many as 8-12 loaves weekly for her family.

The “Laramie Milling and Elevator Company” backers looked upon construction of the Pioneer Canal west of town as another boon to their enterprise. With that resource, farmers would come to the Laramie Plains. Plus, short-season high altitude wheat varieties were under development to boost regional farm output.

Also, the Union Pacific Railroad was actively encouraging agriculture along the railroad line to increase freight revenues. In this new market, the UPRR didn’t know for sure how much to charge for shipping grain to make a profit, so it set freight rates lower for raw wheat than for milled flour—in effect subsidizing the farmers until the railroad had better data.

Therefore, Laramie mill promoters saw no problem in obtaining grain from farms as far away as Oregon or Iowa. They wouldn’t be dependent on local farms.

A major contributing factor in the plan feasibility was the source of power. Several of the most enthusiastic mill backers were also the officers of the Laramie Electric Light Company also under development in 1885. Laramie’s mill would not be dependent on water power.The “flouring mill” (as they called it) was touted as the first manufacturing plant in Laramie that would use electric power, and possibly the first electric flour mill in the world.

In December 1885, electric plant President M.N. Grant was quoted in the Laramie Sentinel as planning “to attach a first-class flouring mill to the establishment [the light plant], the company having ascertained that there will be a reduced rate on grain, and it can be ground here at a handsome profit.” It would give new impetus to Laramie’s infant agricultural interests, the paper claimed. Later, it was revealed that the UPRR had agreed to charge half-price” for delivering equipment in its support for the mill.

Robert M. Jones, one of the investors in the electric company, became its superintendent when it opened in 1886. At the same time, Jones was a major promoter of the flour mill. He had become familiar with the operation of dynamos--one newspaper account says that even Thomas Edison himself was pleased with how “confident and thoroughly conversant” Jones was with the machinery to be used at the electric plant and the proposed mill.

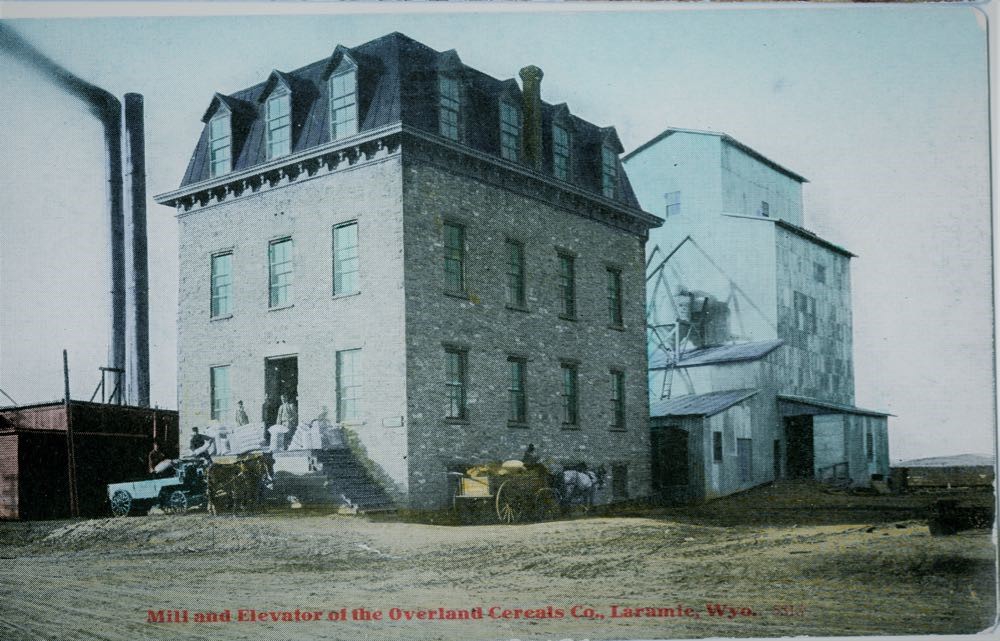

Twenty-five-thousand dollars was raised for the mill; a grand four-story white stone building was under construction throughout 1887 on land adjacent to the light plant, probably leased from the UPRR. The flouring mill could be seen all over town, something to be proud of with its fashionable mansard roof.

Editor Hayford of the Sentinel was an enthusiastic promoter. In late December 1887, he advised townspeople to inspect the facility before it began operation. The 10 carloads of equipment installed “is as pretty and as finely finished as the best parlor furniture,” he claimed.

More importantly, no flour dust and dirt had accumulated as it would later. Actual operation began on February 18, 1888, with “everything running like clockwork” to produce the first sack of flour, the Sentinel reported. Daily output was to be 250 sacks.

However, it closed in less than a year.

The UPRR revised shipping rates--raw grain now cost the same as milled flour. The mill was reorganized and opened up again in April of 1890, but closed within 6 months and was foreclosed upon.

When the Laramie Board of Trade asked for an explanation of why the mill closed in October 1890, Superintendent Smith said it was unfair competition from Colorado and Nebraska flour mills. They reduced their prices to Laramie merchants for flour, with the result that six sacks of out-of-state flour was sold in Laramie for every sack that was locally produced.

Smith claimed that when the Laramie mill closed, those out-of-state mills raised their prices to Laramie merchants, proving their unfair tactics. Smith also pointed out that though the Laramie mill did not compete with Minneapolis flour, it did “come in direct competition with Nebraska and Colorado flour which uses the same wheat as used in Laramie.”

Apparently the Minneapolis Milling Company (now General Mills), founded in 1856, had already established itself as a source of the best flour. Laramie mill operators tried an advertising campaign to get housewives to use only local flour and to demand it from local merchants, but the campaign didn’t work.

The fine building with its equipment apparently sat empty for nine years until W.W. Augspurger of Iowa provided most of the capital to reopen it in July 1909. A contest was held to name the flour produced—Mrs. R. McCarty won, with the name “Overland Flour.” Charles Merica, UW’s eighth president, urged Chamber of Commerce members in 1911 to “buy Overland flour and insist upon its use in the family.” This attitude of shaming the public into buying local continued but ads abruptly stopped in 1922.

That year, the newspaper mentions that the Overland flour mill of Laramie was to be moved and combined with what was left of a flour mill in Cheyenne that was destroyed by fire. By this time, Utah-based Hylton Flour Mill Co. Inc., owned the Laramie mill and many others. However, the plan hit a snag over who was to pay for the move, and it didn’t happen. So 1922 was the end of flour milling in Laramie.

Nothing is left of the fine building but the memory of a foolhardy enterprise that was almost worth trying as Laramie searched to expand its economic base.

By Judy Knight

Caption: Postcard showing Laramie’s flour mill that opened in 1888 and operated sporadically through 1922. It was located close to the UPRR tracks, on Second St. just north of Clark St. Next to it was the Laramie Electric Light plant, whose twin smokestacks can be seen in this photo from around 1915. At the time, the mill had been reopened by its third owner, who expanded it with a grain elevator and grain storage building behind it. Photo courtesy of the Laramie Plains Museum.