Laramie’s 1889-1930s plaster industry started on a fluke: Col. Downey’s visit to UPRR in Omaha directly led to development

Gypsum mineral deposits near Laramie had been known since the early days when prospectors looked for economically viable resources to be exploited. It was part of the franchise for the Union Pacific Railroad (UPRR) from the federal government to develop economic activity in the lands granted the railroad.

Use of gypsum as an interior construction material has been known since antiquity—Egyptian pyramids and ancient Greek buildings used it; deposits near Paris yielded a sculpting material known as “plaster paris.” At Laramie’s founding in 1868, the 1840s gypsum plaster mill at Grand Rapids, Michigan was the furthest west of any in the United States but there was lots of gypsum ore elsewhere, including in Wyoming.

Incidentally, “stucco” is a similar looking material but generally uses lime as a binder, mixed with sand. It is more weather resistant than gypsum plaster, but was also used for interiors before gypsum plaster became abundant. Sometimes it is called “stucco plaster” or “lime plaster.”

Manufacturing process

Gypsum beds were abundant both north and south of Laramie, some even within the city limits, as Hollis Marriott pointed out in her story “Stink Lake in a Sink Hole & other marvels of gypsum” published February 16, 2020 in the Boomerang.

Developing gypsum beds for production of plaster and plaster paris (now called “plaster of paris”) required considerable capital and expertise that competed with other activities in early Laramie, like steel recycling and glass manufacturing.

Gypsum contains a lot of water. To become plaster, the raw ore from the quarry is crushed, then further ground into a consistency like flour. Next, the milled gypsum goes to the heated “calcinating” kettles, where a boiling milky liquid forms—all the water is driven off. At that point it becomes dusty white powdered plaster. For plaster paris, very white gypsum is ground even finer to be marketable. Chemicals are added to slow the setting time, or omitted for medical use in the past to quickly cast broken bones.

Costs include transporting the raw ore and finished product, fuel for boiling, and recognition that demand for building trade use is seasonable—dry storage capacity for the 100 lb. sacks of product is essential. Labor costs were estimated to be $7,000 monthly at one Laramie plant, though nearly all parts of the process were automated except for the quarrying.

Downey recommends Laramie

In 1887, two brothers, H.G. and F.W. Fowler, developed a plaster mill at Blue Rapids, Kansas, convenient to the building boom taking place along the western railroads. Their gypsum deposit was small but successful; the brothers began searching for other larger sites to develop.

The main criteria for the Fowlers was ready access to a railroad. They wrote to the UPRR, wondering if gypsum deposits were anywhere along its route. Railroad officials were about to respond in the negative, but Col. Stephen Downey of Laramie happened to be in their offices on other business at that time.

Downey spoke up and said that there were extensive deposits in Albany County; consequently the railroad turned the matter over to him. Upon returning to Laramie, Downey sent samples to the Fowler brothers in February of 1889. By March, the Fowlers were in Laramie, and were escorted by land owner N.K. Boswell to the gypsum beds near Red Buttes, about 10 miles south of Laramie.

Ultimately, the Fowlers were unable to achieve the freight rate and commitment from the UPRR for the necessary sidetrack needed if a factory were to be established. So the brothers moved on to Utah, where they built a gypsum mining and milling operation.

1889 Red Buttes mill established

However, N.K. Boswell got valuable information from the Fowlers about the viability of such a mill. Boswell went to work immediately on developing the land himself. His partner was J.B. Arthur from Fort Collins who had been mentioned in the newspaper twice in 1888 as visiting Laramie for unspecified business and on May 13, 1889, Arthur and Boswell announced that they were developing a plaster mill at Red Buttes.

In July of 1889, Boswell was in Omaha negotiating a better deal than the Fowlers for freight rates and the necessary sidetrack. A contract was let with an experienced plaster engineer from Grand Rapids, Michigan for the necessary machinery, received in September. On November 2, 1889, the Laramie Sentinel announced that the plaster mill had “started up and is now turning out its products.”

Often referred to as the “Red Buttes Plaster Mill,” the actual name of the company changed periodically. Boswell and Arthur’s company was probably the Consolidated Cement Company—it became the Rocky Mountain Plaster Company by 1892. In 1910 it was acquired by the Western Building Material and Manufacturing Company of Cheyenne, which manufactured wallboard.

On March 30, 1915, the Laramie Republican newspaper announced that the “Red Buttes plaster mill was sold a few days ago to the Sahara Cement and Plaster company of Denver.” By this time there were two other plaster mills operating in Laramie. Early in 1916, the Laramie Republican noted that the Denver owners were planning to put in new equipment to further refine the product into various sizes of plaster paris blocks, to set them apart from other Laramie plaster products. However, that is the last “Sahara” is heard from in the Laramie newspapers examined through 1922. There are indications that the plant ceased to operate.

1896 Standard Plaster begins

Around 1894, William McClary arrived in Laramie as manager of the Red Buttes mill. He realized that the gypsum bed at the southern edge of Laramie, now where Boswell Drive heads east from 3rd St. all the way to 9th St., was also capable of development. It was very close to the UPRR tracks and convenient for employees to walk to the mill, rather than living in company-provided housing, necessary at Red Buttes.

From newspaper accounts, McClary’s role in the development of the deposit at the south edge of Laramie is vague, but sometime in 1896 the Standard Plaster mill went into operation. It was under the direction of W.M. Reese, President, who apparently moved to Laramie from Kansas to take charge of the works, overseeing the construction of the mill and the quarry. It is likely that Reese was employed by the Standard Plaster Company of Ashland, Kansas, incorporated in 1890. By July of 1896, a Laramie tradesman stated in newspaper ads that he could plaster walls in Laramie, using “new plaster from the Standard Plaster Company.”

Acme takes over

McClary’s obituary in 1913 states that he “was instrumental in first interesting local parties in the project and organized the Standard Plaster Company which was later [1902] taken over by the Acme Cement Plaster Company of St. Louis.” McClary’s obituary states that “just west of the Acme plant” another plaster mill called the Overland was located “and Mr. McClary was again called upon to take the management of the new enterprise” which apparently he continued with until the summer of 1913 when he was about to move to Moapa, Nevada to a plaster plant there when he suddenly died of what was called sunstroke. F.A. and L.J. Holliday of Laramie were involved with the Overland Cement Company, according to the August 23,1920 issue of the Republican.

If that information is accurate, the area east of what is now the location of Corona Village Restaurant on Boswell Drive once had two thriving plaster mills with gypsum bed east of the mill locations. There was a railroad spur that brought the material from the main line to the west—servicing the quarry and the mills.

Laramie Cement Plaster Company

The fourth Laramie plaster mill began in the repurposed glass factory on North 3rd St.. That early development had looked promising, but the enterprise was only sustained for about one year before equipment failure caused a fire. That, compounded with high fuel and freight costs that hadn’t been figured into the cost of operation, doomed the enterprise, which was foreclosed upon in 1889 at a considerable loss to local investors.

In 1920, the idea of restarting plaster manufacturing in the old glass factory met with local opposition. A petition among business owners was circulated, asking the city to reject the request from investors. They feared that “dust will blow across the city” from that new operation.

However local investors did secure permission from the city, and it was announced that the latest new equipment was being installed, presumably including some kind of dust abatement measures. Originally the name was going to be “Wyoming” cement plaster, but when incorporated it became Laramie Cement Plaster Company. Local investors were named as Charles L. Patchell, President, R.H. Homer, T.H. Simpson, C.D. Spalding, and William McCune. A major public relations campaign attracted more investors; the mill was planned to employ 40 to 50 men, with a $100,000 investment in Laramie’s economy.

Thus the Laramie Cement Plaster Company began operation in 1921 with ore from a quarry north of Laramie near “W” Hill. The company is mentioned in the 1924-5 Polk City Directory for Laramie. However, by then it may have been purchased by Acme, which then ran two Laramie mills. It is also possible that Acme had produced plaster at the old glass factory much earlier or contracted to operate the mill in 1921 for the local company.

Confusion over names

Plaster companies in the west have difficult histories to trace. They changed ownership frequently, operated more than one mill and/or quarry—a single plant might have had several names and locations—or one company might operate a mill for a different owner. Some of the information presented here may be misleading because of the practice of local writers to continue using the name of the former owners.

A name that turns up in the 1931-2 Polk Directory is United State [sic] Gypsum Co. “1 mi. s. of Laramie.” Exactly which plaster mill that would have been is unknown, it might have been the Overland, which disappears from the City Directories at that time.

Another plaster company in Laramie city directories from 1924-7 is CertainTeed Products Corp, with a location at the “s. end of S. 9th St.” This means that they might have taken over the Acme operation. CertainTeed is not mentioned in Laramie Directories after 1927. However, in 1961, now owned by a French corporation, it opened a plaster mill in Cody. In April of 2020, CertainTeed closed the Cody plant after it was unable to find a buyer—with a loss of 50 jobs according to the Cody Enterprise newspaper. It was the last remaining plaster plant in Wyoming.

Gypsum is so abundant that the dollar value of a 100 lb. sack is low but transportation costs are high. Economic viability is tied to the local building industry. Although Laramie plaster factories were booming from the period of 1889 to mid-1920s, by 1934, the only firm left in the Laramie City Directory was Monolith Portland Midwest Company.

The term “cement” is accurately used to describe anything that bonds things together, though we tend to think of it as the foundation for concrete today. Now Mountain Cement Company of Laramie, successor to Monolith, claims that it has been in operation since 1927, probably tracing its corporate history from one of these “plaster cement” mills of early Laramie.

By Judy Knight

Source: Wyoming Illustrated Monthly, January 1, 1891

Caption: An early sketch of the Red Buttes Plaster mill, the first in the area to open for the manufacture of plaster from the gypsum beds about 10 miles south of Laramie.

Source: Laramie Plains Museum

Caption: A plaster mill near what is now Boswell Drive, showing some of the gypsum bed and the mill with its four smokestacks indicating four “calcining kettles” for removing the water from the gypsum. Very little trace remains of the gypsum quarry or of this large factory, which is probably the enlarged Standard plant, after purchased by the Acme company.

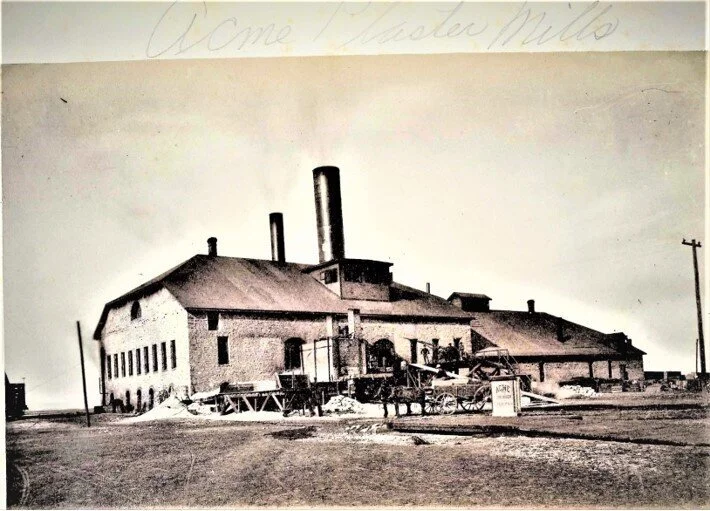

Source: Laramie Plains Museum

Caption: The 1887 glass factory (behind 960 North 3rd St.) lasted one year and the building became vacant. The sign out front indicates that it had been taken over by Acme Cement Plaster Company. Photo is undated; one estimate that it could be from around 1911, but no mention for a plaster mill at this site is in local newspapers until 1920—Laramie Cement Plaster bought the building and began production here in 1921 as noted in the City Directory. A portion still stands, but a new roof is a standard gable, not hip-on-gable as shown, and the dormer is gone.