Bill Nye: humor writer is beloved nationally Laramie and a mule named “Boomerang”—his road to fame

One of America’s celebrated humorists of the 19th century gathered enough material from his seven-year stay in Laramie that his “paragraphing” (as he called it) provided enough fodder for a lifetime. Edgar Wilson Nye (1850-1896), who wrote under the pen name “Bill Nye,” might have remained obscure but for Laramie and a mule named “Boomerang.”

Let’s hope that mule actually existed, but with Bill Nye you never know. One of his books is titled “Forty Liars and Other Lies,” (1882), hinting that truth-telling wasn’t a priority.

Exaggerations

What did become a hallmark of Nye’s storytelling was gross exaggeration and “warm affection for his fellow man,” as one writer put it. He usually made himself the hapless object of ridicule in his stories. “We can never be a nation of snobs so long as we are willing to poke fun at ourselves” he wrote in a piece for Century magazine. Besides, he observed, “there is less chance of being sued.”

But Bill Nye did not poke fun at women or women’s work. Even when telling anecdotes of mishaps around the house, he made himself the victim of events, not the lady of the house. No doubt his wife, Clara Frances Smith (1850-1906), known as “Fanny,” had a lot to put up with if anything he said about running a Laramie household in the 1870s were true.

Laramie Lampooned

Nye was fun to be around and could be counted on for entertainment. He began meeting with a group of men known as the “Forty Liars Club,” a name he borrowed for the title of his second book of essays. The club continued to meet upstairs in Ivinson Hall at 205 S. 2nd St. for years following Nye’s departure from Laramie in 1884.

A typical exaggeration is his description of Laramie:

“Somebody discovered a rich mine out there. A city of 8,000 inhabitants sprang up . . . . the mine proved a failure; boom collapsed; everything fell flat. Everybody who could get away left town . . . I had a weekly newspaper on my hands and had to stay. A queer lot of people staid [his spelling] with me . . . . very few of them could read and had no use for a newspaper anyway except for gun wadding. The only man in Laramie who had much to do was the coroner. He was behind in his orders most of the time. The cemetery was about the only growing thing in town.”

Editor Nye

He did invest in mining stock when he came to Laramie, everyone did, he said. However, he came to Laramie on May 1, 1876 with 35 cents in his pocket, he claimed. Distant friends provided an introduction to the Laramie Sentinel newspaper. Its editor and co-founder, J.H. Hayford, hired him for $12 a week. For a time he lived with the Hayfords, and joked that though he was overpaid for the Sentinel job, or so Hayford thought, he made up for it by taking care of the Hayford children (there were many) and “jerking the press” once in a while. That job lasted two years before he quit. “The children had measles,” he joked, and the job became too much.

However, it’s likely there were many clashes with Hayford, whose writing style was about polar opposite of Nye’s. Though critical of Nye’s journalistic ability, Hayford allowed him to write and publish mostly whatever he wanted, but without bylines. Simultaneously with his newspaper work he studied and practiced law (listing his occupation as “attorney” in the 1880 census), also, he was a Justice of the Peace, then Laramie Postmaster. He became a husband in 1877 and two daughters soon followed: Bessie Loring (1878-1952), and Winifred Louise (1879-1970).

In 1881, and not doing well as an attorney—the authorities urged him to give it up, he quipped—an opportunity came along to purchase stock in a new newspaper company organized by six Laramie businessmen. They wanted a daily Republican-leaning newspaper to out-compete the Sentinel, which by 1881 was only published on Saturdays. The owners tapped Nye as editor, and he picked the name “Boomerang.” He said it was the name of his mule, which always came back. When the paper moved to the second story of a livery stable, he inferred it had an elevator because Boomerang was always tied to the back stairway, and if you wanted to go up, just “pull his tail and he will elevate you.”

Historian T.A. Larson says the Boomerang had a paid circulation of 300 when it started as a weekday paper. But Nye began a weekend edition, the Boomerang Weekly, which featured a tongue-in-cheek summary of the events of the previous week and a humor column by Nye. Soon the paper obtained subscribers all over the country because of his columns. Nye published his first book, “Bill Nye and Boomerang” in 1881, and like most of his later books it was a collection of short humor essays and reprints of newspaper columns.

Early history

One would never get a true picture of Bill Nye’s life from reading “Bill Nye, His Own Life Story,” a book put together posthumously in 1926 by his son Frank from columns Nye had written. He was born in Maine, but grew up in Wisconsin as his farmer father moved west. The land they settled on near River Falls, Wisconsin, Nye described as “composed of a hundred and sixty acres of beautiful ferns and bright young rattlesnakes.”

A roadside sign put up in 1968 by the State of Wisconsin near the Nye family homestead has the quote above, though it also states that the “snakes are gone if they were ever there,” alluding to his tendency toward hyperbole. The marker also mentions that nearby was the country church where Bill Nye, “practiced public speaking to empty pews. He was then a student at River Falls Academy.” The possible practice in public speaking paid off, because later he gained popularity as a lecturer.

Postal wit

There is a hint that the Boomerang investors secured for Nye the job as postmaster to supplement the meager salary they were able to pay him. The “post office” was in the back of W.H. Williston’s Book and Stationery Store at 201 S. 2nd St.. He may have hired assistants to deal with the mail and customers. But he had a lot to say about cowboys who kept moving from one employer to another and complaining if their mail got forwarded to the wrong ranch.

In 1883 it became necessary for Nye to resign as Laramie Postmaster. His letter of resignation is cited by Janice Campbell in her “excellence-in-literature.com” website as a classic. It was originally published posthumously in 1906. Partially quoted below, he claims he wrote this to President Chester A. Arthur:

“To the President of the United States: Sir—I beg leave at this time to officially tender my resignation as postmaster at this place, and in due form to deliver the great seal and the key to the front door of the office . . . . You will find the key under the door-mat, and you had better turn the cat out at night when you close the office. If she does not go readily you can make it clearer to her mind by throwing the cancelling stamp at her . . . . Tears are unavailing . . . . ”

A sad turn

Such a happy-go-lucky person as Nye should not have a tragic turn of events affect him, but it is hard to see the bright side to coming down with meningitis. At the time the disease was diagnosed from inflammation of the meninges, protective coverings of the brain, but there was no cure except rest. It was November of 1882 when he was stricken.

It took a full year for him to even partially recover. Luckily his first two books had been published, bringing some income, but he had to resign from the newspaper as well as the postmaster’s job. It was clear that Laramie was not the place to fully restore his health. When he got well enough to travel in 1884, the family moved to Hudson, Wisconsin, where he got better and continued writing for two years.

While in Wisconsin he published his third book, “Baled Hay,” a title spoof inspired by Walt Whitman’s “Leaves of Grass.” As for the Nye family, two of their eventual four sons were born there, Max Edgar (1886-1907), and Frank Wilson (1887-1963).

A workaholic

Some say Bill Nye never regained his former stamina. But he soon embarked upon a whirlwind of activity. He accepted a job on the staff of the New York World in 1886. Fanny and the children may have stayed behind in Wisconsin for a while because the two sons were born there; he would have had to travel back and forth from New York, using the “Soo Line” for the last leg of that trip—another source of anecdotes for his columns.

Nye’s national reputation was established before he left Laramie. He had become a syndicated columnist even while he was ill in 1883. After he left, he continued to be published in the Laramie Boomerang with humorous letters from wherever he was. In addition to the two published in Laramie, and the one in Wisconsin, two more books came out while he was in New York in 1887, “Remarks by Bill Nye” and “Cordwood.”

In the period between 1886 and 1890, Nye accepted contracts for lecture circuit tours with others who had achieved success reading from their works. There were three such tours, each of several months duration. Train travel and stays in famous and not-so-famous hotels across the country gave him fodder for yet more anecdotes. The poet James Whitcomb Riley often was his partner on the lecture circuit, leading to “Nye and Riley’s Railway Guide,” published in 1888.

In 1889 another son was born, though Edgar Winthrop (1889-1900) died as a toddler. That, and the absences from family may have taken a toll on Bill Nye’s enthusiasm for the lecture circuit. He gave up lecturing and in 1891 the family moved to property he had purchased in the unincorporated community of Buck Shoals, a few miles from Asheville in western North Carolina.

Died too soon

He was only 41 years old, not in the best of health, but he used the time to publish more books such as “History of the United States” in 1894, a humorous take on the dry history textbooks of the time. It was republished in 2007 as “Bill Nye’s Comic History of the United States.” In 1896, the year he died, two more saw print, “Bill Nye’s Comic History of England,” and “Bill Nye’s Sparks.”

At least two more books were published posthumously, and later several compilations by others, his son Frank being one of those compilers. Frank would have been about 9 years old when Bill Nye died, but at least he knew his father, unlike the last son, Douglas. Laramie historian T.A. Larson put a compilation of Nye’s best writings in “Bill Nye’s Western Humor (1975). It focused on good times in Laramie, though it included Nye’s line that he was “out of coal half the time” because his work was not a howling success.

Nye was 45 when he died a week after suffering a stroke. A month later, his widow, Fanny, gave birth to a fourth son, Douglas Day (1896-1977). The Cheyenne Tribune reported that he left “an estate of $35,000”; hundreds of telegrams and letters of condolence from all over the world were received.

Tributes continued to pour in: “Nye was. . . . prominent among those who contributed liberally to human happiness” (Crook County Monitor); “His wit was of the droll style peculiar to the boundless west. . . ” (Asheville Daily Citizen)”;. . . one of the funniest men of the day” (Laramie Boomerang).

The cemetery where he was buried in Fletcher, NC, has not only a marker on his grave but a vine-covered unofficial historical monument to his memory located nearby. He lived in that area even less time than he did in Laramie, but long enough to be remembered fondly.

By Judy Knight

Source: Laramie Plains Museum

A serious Bill Nye, around age 30; the photo was given to Robert Marsh of Laramie, one of the Boomerang founders who hired Nye, setting him on his way to nationwide fame.

Source: Laramie Plains Museum

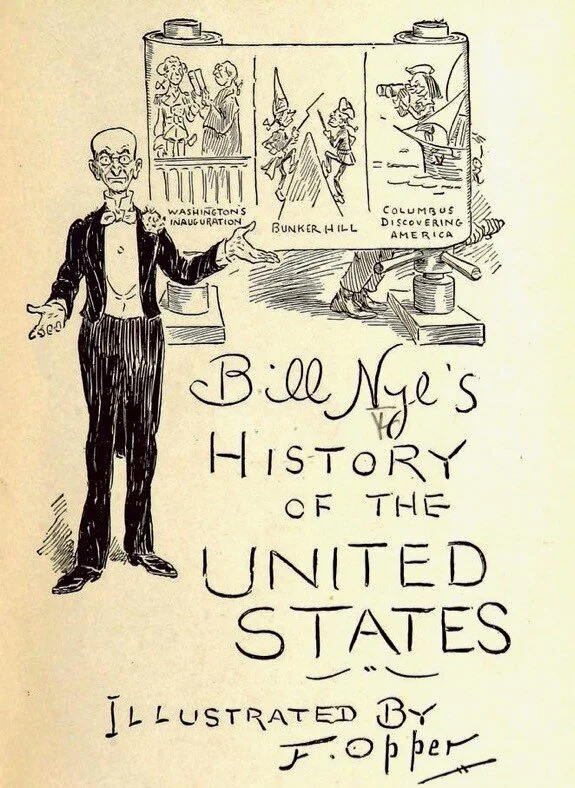

Caption: Cartoonist Fredrick Burr Opper had fun with Bill Nye’s renowned baldness; his amusing illustrations suited Nye’s books. Note the feet under the drawings and the turntable spindle, a comic reference to the way touring theatrical groups unwound different scenes in makeshift theaters

Source: Find A Grave.com

Caption: Nye Monument outside the cemetery. The inscription reads in part: “In Loving Memory of “Bill Nye” American Humorist and Friend. Born in Shirley, Maine August 25, 1850, died at “Buck Shoals” near this spot February 22, 1896. Admitted to the bar 1876; he belonged to the Masonic Fraternity; member of Calvary Episcopal Church, Fletcher, N.C. His body is interred in yonder churchyard. Erected 1925.”