Senator Warren sinks with Titanic!! (re-elected anyway) Breaking news, exclusive from Boomerang

On May 27, 1912, readers of the Laramie Daily Boomerang were shocked to learn that Wyoming’s powerful Senator F.E. Warren had gone down with the great ship Titanic. They already knew of the sinking. It had happened more than a month earlier, and the news traveled the world in less than a day. Why did it take so long for word of Warren’s spectacular demise to reach Wyoming?

Travelers from the Far North

Several years earlier, icebergs from Greenland’s coastal glaciers had fallen into Baffin Bay and started their long journey. They drifted north and then south, 4500 miles in all, melting as they went. Survivors (the largest) reached the North Atlantic in early 1912. There they drifted east with the Gulf Stream.

By mid-April, ship after ship was reporting pack ice and bergs in the westbound transatlantic shipping lane. The ocean liner Niagara suffered two punctures to her hull (quickly patched). The steamer Armenian arrived in Boston with stories of an ice field 70 by 30 miles in size. She was followed by three more steamers, two of which were crippled by ice damage to their hulls.

The liner Carmania was forced to move “dead slow” through ice so thick that individual pieces could not be seen, passing icebergs “mountain-like in size.” Many of her passengers found the experience wonderfully novel. Miss Claudia Sturm said the monstrous bergs were far more grand and inspiring than anything she had seen, though she did concede “it was mighty scary.”

Then on April 14, shortly before midnight, one of the icebergs was hit hard by the world’s largest ship.

Biggest and best no longer

True to her name, the RMS Titanic was huge. She measured 882 feet from bow to stern, had nine decks, weighed 46,329 tons, and was valued at $15 million. For first class passengers, she was a Mansion on the Sea. They slept in elegant rooms, ate seven-course meals, and availed themselves of a smoking room (for men), Turkish baths, and the first ever swimming pool on an ocean liner.

The Titanic was a steamer on a grand scale—159 furnaces heated 29 boilers, consuming 852 tons of coal every day. Smoke poured from three tall funnels (a fourth was fake, added to enhance the image of power). Able to cruise at 21 knots (24 mph), she was projected to cross the Atlantic in just five days. Because of innovative safety features—double hull, 16 watertight compartments, the latest Marconi wireless telegraph—the ship was “practically unsinkable.”

On April 10 at noon, the Titanic left Southhampton, England, on her maiden voyage, bound for New York City. The fourth day out, she met the ice pack, and just before midnight, struck an iceberg nearly head on. It ripped open the double hull, and destroyed six watertight compartments. The Titanic began to sink, the captain issued an order to abandon ship, flotation jackets were distributed, and lifeboats were lowered as passengers rushed to board them.

All the while, the radio operator repeatedly called for help. He reached Halifax, Nova Scotia, but the new technology proved less than perfect. Some messages were garbled, possibly mixed with calls from another ship. The last distress signal was received about two hours after the collision.

Ships at sea also picked up the SOS signals as well as the ship’s location, and immediately headed her way. The Carpathia was the first to arrive, about four hours after being notified. But the Titanic was gone, marked only by floating remains. After rescuing passengers from their lifeboats, the Carpathia sailed straight to New York City, docking on April 18. But the news traveled much faster, arriving just hours after the collision.

News wirelessed world-wide instantaneously

It was an exciting time for communication technology, especially at sea. Prior to the 20th century, ships beyond visual range had been very much isolated. There was no way to know if a ship was in trouble or lost unless it failed to arrive at its destination—a decision that couldn’t confidently be made for weeks in some cases. But in 1901, wireless telegraphy came to the rescue.

That year, Guglielmo Marconi successfully sent a message across the Atlantic using radio waves. In contrast to a traditional telegraph, no wires connected his transmitter and receiver, hence the name “wireless” (in 1920, “wireless” became “radio”). It wasn’t long before wireless was indispensable technology on ocean-going ships. Without it, none of the Titanic’s 2200 passengers would have survived.

Wireless was revolutionary in another way, similar to the internet almost a century later. News could now travel widely, and at unbelievable speeds! On April 15, less than half a day after the collision, the disaster began to hit front pages across the U.S. It was a dreadful story, but with a happy ending.

“Biggest Steamer Ever Afloat Crumpled Up Like Toy—Wireless Saves 2,000” declared Chicago’s Day Book. “Most Thrilling Story of the Sea, 2200 on Board, All Saved from Watery Grave” according to the Daily Gate City in Iowa. “Titanic Passengers Safe, Virginian Towing Great Disabled Liner into Halifax” reported the Baltimore Evening Sun. Laramie’s Daily Boomerang gave brief coverage to the disaster on a corner of the front page. “Most luxurious of all floating palaces may never reach end of first voyage. Collided with big iceberg. Passengers were all taken off.”

But it wasn’t long before these papers realized that they too were Titanic victims. The news may have been speedy, but it was wrong.

Faith in human accomplishment shaken

The next day, April 16, the same papers delivered a very different message—one of great tragedy. The Titanic sank to the bottom just two hours after she hit the iceberg; there was no hope of salvage. Most aboard were lost to the frigid waters of the North Atlantic, their final resting place unknown. Only 340 bodies were recovered.

Most tragic, the Titanic carried just twenty lifeboats, far less than was needed for the 2200 people aboard. And in the rush and confusion, they weren’t filled to capacity. Though all women and children were to board first, along with sailors to steer them to safety, almost half the lifeboat passengers were men (to be fair, male passengers outnumbered female 3 to 1). In the final tally, there were 705 survivors, among them Mrs. F.M. Warren.

More tragic news reaches Laramie, by way of Glasgow

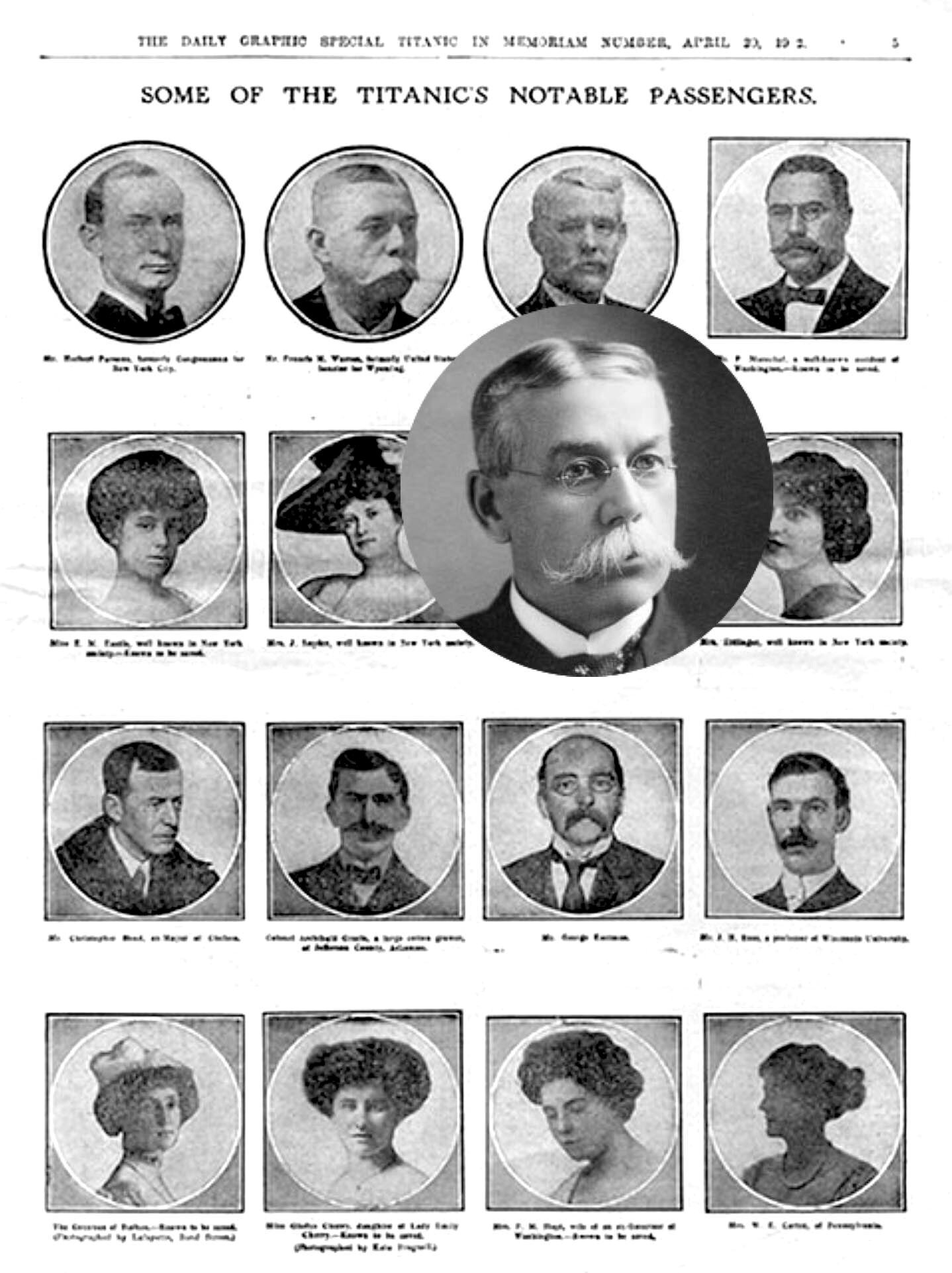

For the remainder of April, Laramie papers were rarely without Titanic news—survivors’ harrowing tales, grisly accounts from the Morgue Ship, scandalous results from official investigations on both sides of the Atlantic. But by May, content was returning to normal. Then Laramie’s Justice John Reid received a month-old newspaper from his friend Jesse Weir in Glasgow, Scotland (formerly Jesse McGill, of the Laramie McGills). It was the “Titanic In Memoriam” issue of London’s Daily Graphic, published April 20, 1912.

With twenty pages of dramatic woodcuts and line drawings, the Graphic lived up to its name. The cover featured the Titanic, her bow cutting cleanly through rough seas past an iceberg to starboard; all four funnels poured out black smoke. On page 2, a map of the North Atlantic showed the actual location of the collision, marked with drawings of the Titanic and the deadly berg. The centerfold provided a full-length view of the world’s largest ship, above illustrations of magnificent icebergs.

It was page 5 that interested Reid, and surely the reason Jesse Weir sent him the paper. Among the photographic portraits of the Titanic’s notable passengers was “Francis M. Warren, formerly United States Senator for Wyoming.”

Wyoming’s rich Republican mogul

Francis Emroy Warren arrived in Wyoming in May of 1868, age 24. Fifteen years later, through ranching and business, he had become one of Wyoming’s wealthiest men. By 1912, he could easily afford two first class tickets aboard the Titanic (for his wife and himself).

Warren also was politically powerful. A U.S. Senator since 1895, he was undisputed boss of Wyoming’s Republican party (the Warren Machine), and had solid support across the state, due to the largesse of pork he procured year after year. By 1912, a million federal dollars had been spent on public buildings and sites in Wyoming thanks to Warren.

Knowing the newsworthiness of the senator’s “demise,” Justice Reid delivered the Graphic to the office of the Boomerang, Laramie’s Democrat-leaning paper (the other side read the Laramie Republican paper). Less than a week later, the shocking news was out: “SENATOR WARREN IS NUMBERED WITH LOST.”

While the headline surely hooked many readers, few if any could take it seriously. Warren was in the news regularly, not for traveling abroad but for his accomplishments in Washington D.C. “How the senator came to be numbered among the victims of the disaster is a wonder,” declared the Boomerang.

But a look ahead suggested an explanation: Warren would be up for reelection in November. “Was it premonition?” asked the Boomerang. “One cannot help but believe that the [Graphic] merely made a mistake of a few months, meaning that Senator Warren will be a political victim instead of a Titanic victim.”

Francis E. survives politically, Frank M. lost at sea

Contrary to the Graphic’s “premonition,” Warren easily won reelection. Only after his death in 1927, at age 85, did he become “formerly United States Senator for Wyoming.” Though neither he nor Mrs. Warren were aboard the Titanic, the Graphic inexplicably substituted Wyoming’s senator for Frank Manley Warren, an Oregon millionaire returning home after vacationing in Europe with his wife. Mrs. F.M. Warren was able to board a lifeboat, and was rescued by the Carpathia. But Frank went down with the great ship Titanic.

By Hollis Marriott

Sources: The Daily Graphic, London, April 20, 1912; Wyoming State Archives

Caption: Among notable passengers: top row, second from left is “Francis M. Warren, formerly United States Senator for Wyoming.” Inset shows a younger F.M.Warren.

Source: Wyoming Newspapers (online), Wyoming State Library

Caption: Composite of headlines from front page of the Laramie Daily Boomerang, April 16, 1912.

Caption: This may be the iceberg hit by the Titanic. With its tall peak, it matches some survivors’ descriptions. Photo taken the morning after the collision by chief steward of the liner Prinz Adalbert.