J.H. Brazier, superintendent of the “huge monster” Shows how rail is made in Laramie—1875

The Union Pacific Railroad (UPRR) reached Laramie in May 1868. Constant traffic caused wear and tear on the rails—worn rails could be recycled for reuse. Factories to do the job were called “rolling mills,” and in 1875 the railroad decided to build a plant for this purpose in Wyoming. Fierce competition arose among the cities of Evanston, Cheyenne and Laramie to be the site.

The mill promised good jobs for the city that won out. Laramie offered large tax offsets and was awarded the prize. The UPRR selected experienced rolling mill operator John Henry Brazier (1836-1908) to be the superintendent of the enterprise. Brazier arrived in early 1875 from Ohio and told the newspaper that he was very pleased with the community and the work that had been done to get the factory built.

Huge Monster

A great number of citizens were on hand on April 15, 1875 to see the first iron rolled from the new mill in Laramie. They all wanted to see the “huge monster” at work.

It was a big spectacle according to the account in the Laramie Daily Sentinel the next day. Brazier, the superintendent, “pulled off his coat, took the huge tongs in his hands and ordered the big engine started, and showed all in attendance how the thing was done.” Brazier told the Sentinel that he had put up at least five rolling mills in the past, and he considered Laramie’s mill the best and most perfect one he had ever seen. About 75-90 tons of iron, re-rolled, would be the average day’s work, he said. Two hundred men were to be hired to run the mill—but Brazier had expressed concern about where the new employees would live, since housing was scarce, and he preferred to hire men with families.

J.H. Brazier

John Henry Brazier, or J.H. as he was called, was born in West Bromwich, England in 1836. He immigrated to Boston, Massachusetts in 1850 with his parents and siblings. By 1859 he had relocated to Pottsville, Pennsylvania. He married Mary Ann Brown there; eventually they had three children. Their two older children were Alice and Walter, daughter Maude was born in 1872 after the family moved to Ohio. Apparently J.H. Brazier had a good singing voice as he is listed as a soloist for a “Grand Concert assisted by a galaxy of home talent” at the Sandusky Opera House in 1873.

Civil War draft registrations give occupations: J.H. Brazier as a “roller” and brother Edwin as a “heater,” showing that both were employed in some kind of iron mill in Pennsylvania. Civil War service for J.H. involved bridge building. The author’s great uncle passed down a story that after the War the Brown and the J.H. Brazier families of Pennsylvania moved to Chattanooga, Tennessee, for jobs rebuilding southern infrastructure. His previous experience with iron-working proved useful for J.H.

Chattanooga and Sandusky

During the Civil War the Confederacy found it necessary to build a mill to replace railroad rails bent and destroyed by the contending armies. Chattanooga was selected but before it could be completed Federal troops forced the Confederacy to abandon Chattanooga. General Grant gave the Union Army permission to complete the rolling mill. A few heating furnaces and a roll train were completed under the supervision of T. W. Yardley assisted by J. H. Brazier and James Duncan.

In 1865 the United States government quit the rolling mill business selling the mill and it was renamed the Southern Iron company. In 1870 the blast furnaces at Rockwood and the rolling mill at Chattanooga were merged and the rolling mill later became known as the Roane Iron Works.

J.H. Brazier was listed in the 1870 U.S. census as the superintendent of the rolling mill in Chattanooga. At the same time, J.H.’s brother Edwin was in Brookville, Virginia.

J.H. also invested in property in Chattanooga. But all was not well in his personal finances. The Chattanooga Times of August 25, 1873 noted that John Lewis was suing J.H. for debts. Later, Brazier’s assets, amounting to seven different downtown Chattanooga properties, were sold on the courthouse steps in lieu of payment.

But Brazier did not stick around for the sale; in 1872 he and his family were in Ohio. The Silicone Steel works was being built in Sandusky, and J.H. became the construction manager for the innovative new plant. When the plant began operation, in August 1873, his brother Edwin D. Brazier was hired as the superintendent. Both brothers continued to be listed as superintendents in Sandusky city directories.

There are indications that before the Sandusky plant’s construction, J.H. Brazier may have been the construction manager for another rolling mill in the area of Columbus, Ohio, where local iron deposits were being developed after the Civil War.

Laramie Rolling Mill

In early 1875, J.H. Brazier was hired to be the superintendent of the new rolling mill that the UPRR was building in Laramie—he brought his family here from Ohio. The J.H. Brazier household in the Laramie 1880 census also lists Mary’s mother, Alice Brown. By that time, Brazier had been the superintendent of the Laramie Rolling Mills for five years.

Brazier appears to have been well liked by his Laramie employees. On October 7, 1878, William Connor posted a notice in the Laramie Sentinel praising Brazier for paying him wages when he quit without the requisite two weeks’ notice.

Brazier also introduced several labor-saving and safety innovations at the rolling mill. A set of automatic rollers were installed to move the old rails to the furnaces so men did not have to handle them. Additionally, cranes were set up to move rails from the mill to freight cars, again eliminating the hazardous manual task.

Brazier also hoped to expand the enterprise when he had samples of local iron ore assayed in 1880 with an eye to opening a blast furnace. Unfortunately for the Laramie community, the proposal did not prove feasible.

The Braziers were socially prominent in Laramie, as befitting anyone who offered jobs to hundreds of local men. An elaborate party the Braziers hosted on August 15, 1878 was for their daughter Alice, who had recently returned home from school in Chicago.

A platform was erected in the yard in the front of the Brazier’s home (probably located on North Second St. but no longer standing). It was surrounded with locomotive headlights and Chinese lanterns, where, according to the Sentinel, “The happy guests, to the number of thirty to forty, tripped the light fantastic until late into the night. A superb supper was provided by the host and hostess, with no expense spared to make the occasion eclipse anything of the kind ever before given in Laramie.”

Scrymser takes over

Unfortunately, Brazier's health began to fail due to kidney problems, and he left for California in October 1880, hoping for relief. His brother Edwin was called from the rolling mill he was then managing in Topeka, Kansas, to manage the Laramie Rolling Mill in his brother’s absence.

Apparently the California sojourn was successful and J.H. returned to Laramie shortly. Both brothers went to Topeka almost as soon as J.H. returned. Mary Brazier and their children moved to Kansas too, so the move was to be permanent. It is likely that Edwin, still manager of the Topeka rolling mill, found work for his brother there.

After the Braziers left Laramie, Assistant Superintendent Frederick E. Scrymser became the Laramie rolling mill superintendent. The UPRR closed the mill for a short time but Scrymser was successful in reopening it in the spring of 1885 as “lessee” for the UPRR, and was its manager. He also became president of the Wyoming National Bank in the late 1880s before his tragic drowning in a boating accident at Hutton Lake in October of 1891.

Meanwhile, J.H. had become the superintendent of a rolling mill in Detroit—the family is listed through 1889 in Detroit City Directories. In 1893 we know that his wife lived in Pueblo, Colorado, where there was yet another rolling mill—evidence that J.H. was employed there has not yet been discovered.

J.H. returned to the Laramie area for a short time around 1900, but his family stayed behind. J.H. is listed living as a boarder without his wife in the Laramie census of 1900 and once again gives his occupation as the superintendent of the rolling mill. It is likely that Scrymser retained the lease on the Laramie Rolling Mill, but asked Brazier to return as superintendent. After Scrymser died, another businessman and a bank official, Otto Gramm of Laramie, became lessee of the mill and served as his own superintendent.

Mining misadventure

But Brazier did not immediately leave the Laramie area. In 1902, according to The Semi-Weekly Boomerang, he worked as a machinist at the stamp mill in Jelm. While there, he fell off a building and fractured his arm, which was reported in many papers at that time, even as far away as Salt Lake City.

At the end of his life J.H. lived in Detroit, where he died at the home of his daughter Maude in 1908, at the age of 72. According to his obituary in the Detroit Free Press, he had broken his leg falling down the steps the year before and that injury contributed to his death. He and his wife are buried in Woodmere Cemetery, Detroit.

He didn’t live to see a huge loss to Laramie. On November 8, 1910, the Laramie Rolling Mill was completely destroyed by fire with a total loss of $75,000. The fire started from an overheated smokestack. The mill employed about 100 men per shift and was not rebuilt because of its competitor in Pueblo, Colorado. The destruction of the mill put nearly 300 Laramie men out of work.

By Claudia O’Leary

Editor’s Note: Claudia O’Leary, of Florida, is a family genealogist and retired graphic designer for the Fort Lauderdale Sun Sentinel. J.H. Brazier’s wife, Mary Ann Brown Brazier, was the aunt of O’Leary’s great-grandfather. O’Leary also says: “J. H. Brazier’s daughter Alice married Harry Chase Safford in 1884, who, while living in Kansas, was a law partner with Charles Curtis. Mr. Curtis was the first Native American and the first person of color to hold the office of Vice President of the United States [under Herbert Hoover]. He was also the highest-ranking enrolled Native American ever to serve in the federal government.”

Source: Laramie Plains Museum, Roach Collection

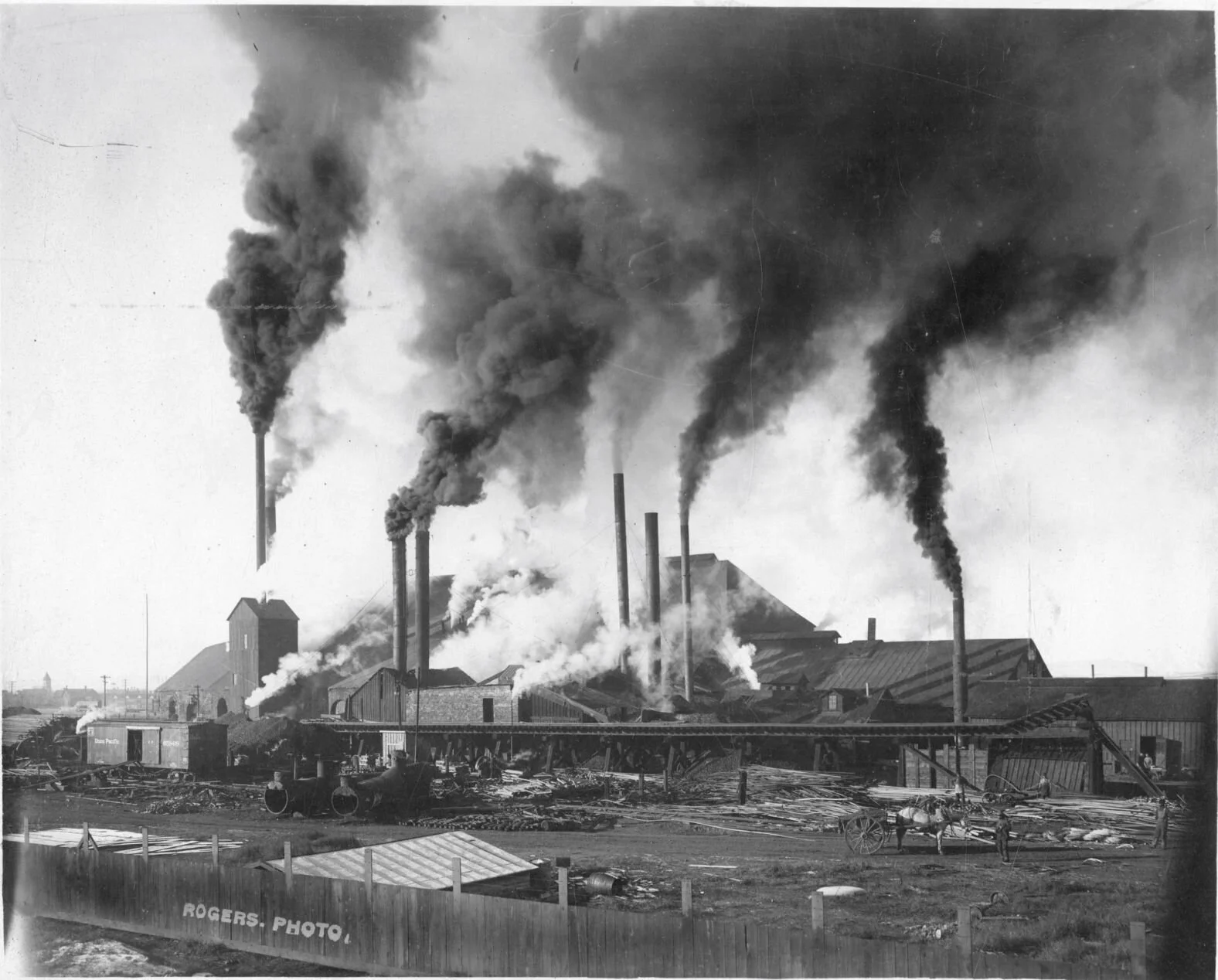

Caption: The Union Pacific Rolling Mill in Laramie, soon after it opened in April 1875, with J.H. Brazier as its first superintendent. The mill site was where the Safeway Plaza is on N. 3rd St. in Laramie today.

Source: Courtesy photo

Caption: “Rolling Mill, U.S. Mill Iron Works, Chattanooga, Tenn.” is inscribed on this photo from around 1865. It flies the U.S. flag (as opposed to Confederate) and J.H. Brazier was mill superintendent. The mill, started and abandoned during the Civil War, was put into operation 1865 after it was seized by Union forces in 1863. Chattanooga’s mayor called it the “Pittsburg of the south.”

Source: Laramie Plains Museum

Caption: Laramie rolling mill in full operation circa 1905