Carrie Burton Overton - First African American Girl To Attend the University of Wyoming.

Early Years in Laramie

For many years a long hallway in the Laramie Plains Museum’s Ivinson mansion has displayed a 1972 newspaper article titled “Lady in the Mansion, Author Both Fascinating Women.”[1] It is a reminiscence of the childhood interaction of Carrie Burton, an African American girl, and wealthy Laramie, Wyoming, resident Mrs. Jane Ivinson.[2]

Of the 8,207 residents enumerated in the 1900 census for Laramie, Wyoming, ninety were African American. Of these, seven were girls of school age, but only two were enrolled.[3] Although not written about in any historical overview of Laramie, one, Carrie Burton, would overcome adversity and go on to be the first African American woman to attend the University of Wyoming, a well-known New Yorker and the woman profiled in the 1972 Boomerang article.[4]

Born in Laramie, Wyoming Territory, 20 July 1888, Carrie was the youngest of two children of her mother, Catherine. Katie, as she was known and whose maiden name was Clasby, was born into slavery in northwest Missouri in 1860. At an early age Katie was separated from her mother when her mother was sold by the white family (Clasbys) who owned her. Freed as a result of the Civil War, Katie nevertheless stayed with the white family for a few more years and eventually first married in her native state a man named Carroll. There, Carrie’s half-brother Bennie, some 5 years older, was born in 1883. Katie Carroll and Bennie moved to Laramie in 1887, reportedly after the death of her first husband.[5] She would marry a second time to John Burton, Carrie’s father. Although no records of the marriage or divorce have been found, the union did not last long; Katie ended the relationship for good reason.

John R. Burton was born in Missouri 26 March 1860 and he may have been reported in the Laramie census of 1880 as a single man living with his mother, Losea, who was listed as a prostitute.[6] Other available records only show his criminal activity. Burton was arrested two times. The first was in October 1890 when Carrie was only two years old. Charged with burglary and attempted rape, he was convicted and sentenced on the 21st of that month to two years in the federal penitentiary in Joliet, Illinois. Burton returned to Laramie sometime after his release and was arrested again in September 1903 for disturbing the peace. He was released and the charges were dropped.[7] He was not reported in the Laramie area again, and likely left the state.

It is not known if Carrie Burton knew of her father’s first arrest due to her young age. Moreover, she may not even have known John Burton was her father or if he was alive. A newspaper article carried in the Laramie Boomerang on 23 July 1900 stated that Burton had died at an earlier date.[8] Conversely, given Laramie’s small size and the later arrest, it is possible that gossip may have revealed the story of her absent father. In any case, Carrie would have little or no contact with her father until much later in life.

After arriving in Laramie, Katie Burton lived at 701 South 4th Street and worked as a laundress. In particular, employment in the home of pianist Mrs. Winant Oliver was arranged so Carrie could receive piano lessons for free.[9] After the marriage to Burton ended, Katie would enter into a third marriage. On 13 November 1895 Katie Burton and Thomas Price were issued a marriage license. An announcement was carried on page four of the Laramie Daily Republican which stated Thomas Price and Carrie (sic) Burton “two well-known colored residents of this city” had been granted a license by the county clerk. The paper reported exactly what the clerk had recorded. Why he confused the mother with the daughter is not clear, but young Carrie was already becoming known in the city for her musical ability and this could have tripped up the clerk

Thomas Price, who was born into slavery in Knoxville, Tennessee, in September, 1842, came to Laramie about 1876. Price was in the Union Army during the civil war, serving in Company B of the 40th Regiment U.S. Colored Troops.[10] His dates of service were from 1861 to 1866 when the regiment was mustered out. The unit was formed in Tennessee and mostly served as protection for railroads in that state.

When that unit was disbanded, Price later transferred to Company E 9th Cavalry Regiment (the famous Buffalo Soldiers). The regiment was formed in late 1866 from existing Army troops and was stationed in western Texas as part of the occupation forces following the defeat of the Confederacy. They remained at Fort Stockton, Texas, through 1875. Price left the 9th after five years, and his arrival in Laramie would coincide with the departure of the 9th from Texas and its move to New Mexico in 1876.[11]

Census records and city directories show Price was employed in and around Laramie at various times as a cook, a laborer, a saloon porter and at the Union Pacific Railroad’s rolling mill. Other than his obituary and his application for a marriage license, he appears in the local papers only sporadically. On 20 October 1893, Price was accosted by one Thomas Watkins who felt Price was giving “attentions to a colored lady acquaintance" whom Watkins had his eye on. A fight ensued and Price, who residents said was a “peaceable man” got Watkins on the ground. Watkins, however, managed to pull Price’s head toward him and disarmed Price by “grasping the upper lip between his teeth, he bit out half the lip on the right hand side.” Luckily the local doctor was able to reattach the bitten off portion.[12] Price was also listed as a “nurse” for a Union Pacific railroad conductor suffering from smallpox in 1894.[13]

Little is known from Laramie papers of the relationship Carrie had with her step-father, but she did remark on one aspect of it many years later. In 1940, in an interview with the Baltimore Afro-American, Carrie stated that her father formed one facet of her musical foundation. She noted, “My father had been a cook for cowboy camps. He knew all about life on the range and the great roundups. He roamed the great West and knew and sang its famous songs.”[14] She did not mention his service with the U.S. Army in that article but did acknowledge his service when she was interviewed for her oral history.[15]

Carrie Burton thought very highly of her mother. In that same oral history interview, she pointedly remarked that Katie was a wonderful mother (emphasis in the original transcript). Katie not only took in washing to support her daughter, but she made sure the young girl regularly attended Sunday school and was enrolled in public schools as early as possible. Katie’s husband, Thomas Price, died in 1910. Carrie, who was by then living in Washington D.C., had her mother moved to the capital city where she cared for Katie, rented a room for her and saw to all her needs.

Outside the loving environment of her home, young Carrie Burton suffered the indignities of racism. According to her oral history interview, at age five she was first asked why she was black. Her mother assured her that God made her that way. Racial epithets would be directed at her frequently, even by those she considered friends. She told the interviewer, however, that she would respond in kind and that the friendships never suffered as a result.[16]

While early Wyoming laws discriminated against African Americans with respect to marriage and education, those laws were eventually overturned.[17] However, it is evident that attitudes were slow to change and would have certainly impacted Laramie’s African American community. Perhaps the tenor of the times in Laramie was best summed up by the Laramie Boomerang in a 1908 article about Carrie. The message was clear; she succeeded despite prejudice against her race.

Most people in Laramie know Miss Carrie Burton but we undertake to say that not many appreciate what she has done for herself or the conditions under which she has worked. Born in Laramie July 20, 1888, she is now just past twenty years of age, a colored girl who has had to face the prejudice against her race, yet so careful to avoid being in anyway offensive to others, so kind and considerate of other’s rights, that whether in the classroom or on the streets she has been universally recognized as deserving of the most respectful consideration.[18]

That tenor was reinforced by an ugly incident that took place only two blocks from Carrie’s home in August, 1904. An African American prisoner in the county jail was accused of attacking a white female worker. The incident ended in a shocking manner when prisoner Joe Martin was forcibly removed from the jail by a mob and lynched from a nearby light post.[19] To make the incident even worse, the mob then shot at the body as it hung from the post. Despite the efforts of District Judge Charles Carpenter, the perpetrators were never brought to justice.[20]

Looking back in 1969, Carrie seemed to have rather mixed feelings about her treatment in Laramie. She stated that there was no real prejudice, yet also contended that she was discriminated against at times in school. On balance, it appears that she was treated well by the community. She was aided in her musical studies by the gift of a piano and she made friends with the children of the wealthy Corthell family.[21] She was mentored by members of her church and always touted for her accomplishments, both while living in Laramie and when she returned later for visits. In 1969 Carrie put it this way, “I have found there is no place like Laramie for good people. Everybody helped. Everybody in town felt we were family (emphasis in the original transcript).[22]

Carrie’s early years were not, however, without painful experiences. In March 1900, 11-year-old Carrie was molested in her home by an itinerant white “fortune teller.” Carrie was there alone with her half-brother Bennie Carroll when the stranger, identified as Cornelius Mannix,” was let into the house. Bennie then left the room after Mannix said Carrie’s fortune could only be told when the pair was alone. Bennie kept an eye out and saw the man “take the girl on his knees and soon began to make improper use of his hands.” Bennie confronted the man with a pistol and chased him from the house. [23]

Carrie’s mother immediately reported the incident to the police and Mannix was apprehended, only to escape confinement while awaiting trial. He was eventually captured in Omaha, Nebraska, and returned to Laramie where he was convicted of the crime, despite pleas for leniency by his wife.

A second tragedy struck the family only four months later. Bennie and a group of friends went swimming in the Laramie River on the west edge of town. They were apparently overcome by cramps brought on by the cold water. All managed to get out of the stream except Bennie and Paul May Jr., both of whom drowned.

May’s body was recovered almost immediately, but it took two days and much effort by community members to recover Bennie’s body. His obituary noted that he was 17 years old, had been born in St. Joseph, Missouri, and had come to Laramie with his mother after his father died. Locally, he was known as Bennie Burton, taking the name of his mother’s second husband.[24]

The drowning and its aftermath also shows the standing of the family in the community, for better or worse. At the time of Bennie’s death their small residence, owned by John Grover, was in the best part of town at the corner of 9th and Thornburgh Streets (later Ivinson Avenue).[25] Yet with both parents working, the family was still not able to afford the cost of a private burial. The community rallied around them and donated the 54 dollars needed to spare them the “humiliation” of a county burial. It is also possible that the same people paid for the granite grave marker in Laramie’s Greenhill Cemetery.[26]

Yet a third traumatic incident would befall the Price family in 1901. Carrie was arrested in Cheyenne, along with her friend Mattie Jones, for the theft of money from Jones’ father.[27] Mattie, who was two years older than 13-year-old Carrie, had met a man named Emmanuel Franklin (aka Manual Cortez), who persuaded her to steal a small amount of money from her father. He then enticed Mattie to meet him in Denver. Mattie apparently talked Carrie into going along with the escapade.

The pair managed to obtain tickets for the train to Denver. When they got to Cheyenne, they met up with Franklin, cashed in the tickets for the remaining value and gave it to Franklin. They were apprehended by the local police shortly thereafter and were sent back to Laramie. The authorities came to understand the idea was all Mattie’s and Carrie was released from custody. As the incident was extensively covered in the newspapers, it must have caused great embarrassment to Mr. and Mrs. Price. Franklin was subsequently arrested in Nebraska and returned to Laramie where he was convicted of grand larceny.

This event, and an admonishment from her Sunday school teacher, may have been the catalysts that ensured Carrie stayed on the straight and narrow. Surely she would have been disciplined by her parents and, as she noted in 1942, another major influence came from her church. She stated, “My life has been little less than phenomenal and I owe most of it to Dr. Aven Nelson who set me straight when he was superintendent of Sunday school.” [28]

Public School

In 1895 at age seven, just before her mother married Thomas Price, Carrie entered the Laramie public school system. The 1908 article cited above also noted in retrospect that in public school she gave “particular attention to music studies.” Carrie would excel in school, earning entrance into higher education which would lead to success in later life.

It is a testament to Carrie’s mother, Katie Burton Price, that she had the foresight to enroll Carrie in school. There were compulsory attendance laws on the books at the time, but they were seldom enforced and Carrie’s help at home would surely have been appreciated.[29] Even then, the 1887 law that required compulsory school attendance only required three months.[30] It would remain that way the entire time Carrie was in school even though the normal school year was divided into two four month sessions. Given her completion of eight grades in public school by age 14, it is apparent that she attended for more than the three-month minimum.

By all accounts, Carrie was a gifted student, especially in music. Numerous articles appeared in the local papers noting her recitals and participation in school musical events. She also performed for her Methodist Church and was a budding writer. Particular note was paid by the Boomerang to her entry in its October 1902 essay competition. Carrie won second prize for her story titled, “Autobiography of a Piece of Pie.” The article noted that it was absolutely original and showed “powerful imagination” as well as Carrie’s ability to express herself. The somewhat quirky tale was printed in its entirety in one column on page four of the Sunday Supplement. The first few lines give the tone of the piece.

I am a small piece of pumpkin pie and have had many adventures some of which I will tell you.

I was once a small seed baby and was planted with many other companions but at last outgrew them all and became so large that one day a boy came and cut me from the vine.

As he was carrying me along, he met a farmer who said, “Where did you get that large pumpkin?” “Papa planted it last spring,” said the boy and I was so delighted that I jumped on the ground – the result being a severe headache.

Records of what Carrie might have studied in public school are sketchy, but indications are that it was much more than the oft repeated “readin’, ritin’ and rithmatic’” curriculum prevalent in those early days. What is known is that shortly after Carrie left Laramie public schools and entered into the University of Wyoming, Superintendent of Schools in Laramie, F. W. Lee, wrote in 1906 that grammar school children were additionally required to study history, geography, grammar and composition. He went on to remark that it was noteworthy that they also studied art and music (the latter at which Carrie excelled) even though until recently Lee said they had been considered “fads.”[31]

When the Laramie Boomerang printed the August, 1908, article on Carrie’s Laramie recital, it noted that she passed through all eight grades of public school “then available” before leaving to attend the University of Wyoming in 1903. While Carrie attended public school only through grade eight, at least two further grades of high school were offered in Laramie. In fact, high school classes were offered as early as 1876 and varied in length with grades 9, 10 and 11 offered at different times. Evidently the Boomerang reporter missed this important fact.[32] Moreover, newspaper reporting indicates that grade 9 was offered in 1902 and grades 9 and 10 in 1903.

Why then would Carrie move on to the university instead of attending public high school? Carrie and her mother may have decided that the public schools were not the place for her to take high school classes. Though it is not certain, this may have been caused by the 1900 controversy in Laramie over the mere existence of high school classes in the public schools. In September 1900, Superintendent F. W. Lee stated grades 9 and 10 would be discontinued in Laramie public schools.[33] The article appeared to tie this to overcrowding in the classrooms. It went on to say that the president and faculty at the University of Wyoming had agreed to allow Laramie students who finished 8th grade to enter the university, likely for most of them in the university’s Preparatory School. That would have taken as many as 60 students out of the public schools. However, another article on the same page, "School Opened Today," clearly stated that grades 9 and 10 would still be offered and it implied that this was a result of teacher and pupil concerns. Doubts over the viability of the high school curriculum may have lingered.

Several other factors may have also influenced the decision to move on to the university. First, from the beginning of classes the year before Carrie was born, the University of Wyoming had grown markedly. The faculty, which had originally been stretched very thin, was now larger to better meet the needs of the school and its students. New buildings had been constructed and sources of funding were more adequate.[34] A quality education was assured to those who enrolled.

Second was the matter of cost. A year after Carrie was born, voters of Wyoming approved a constitution for the soon to be new state that required instruction at the university “be as nearly free as possible.”[35] When Carrie entered in 1903, the university’s official bulletin noted there was no charge; the students were only required to pay for items of personal use such as paper and pens. A third inducement was that the Wyoming State Constitution also explicitly stated that the university would be open to students “of both sexes, irrespective of race or color.”

Fourth, Carrie could take additional high school level classes in the university’s Preparatory School and vocational classes in the School of Commerce at the same time. The combination would allow her to learn a skilled occupation much faster than if she had remained in the public school. Finally, it did not hurt that Carrie and her family lived across the street from the building where most instruction took place.

University of Wyoming

When Carrie Burton entered the university in the fall of 1903, she was the first African American female ever to do so, a milestone for Wyoming history.[36] She enrolled in both the Preparatory School and the School of Commerce. The University of Wyoming at the time would not be recognized by those who are familiar with the university in 2016. The student body was very small and included not only those pursuing bachelor’s and master’s degrees, but also those who were finishing high school course work and those who were taking vocational classes to prepare for future employment. Even 20 years after its 1886 founding, on average there were 35-40 students enrolled in the Preparatory School, 80-100 studying for a bachelor’s degree or a vocational certificate and four to five taking courses in the graduate school.

The Preparatory School was established at U.W. at its inception to provide high school level classes to those students who lacked the opportunity to attend high school in their hometowns. Laramie residents like Carrie, however, were also allowed to take advantage of its opportunities. The School of Commerce (at the time called the Business College) was added to the university in 1899. President Elmer Smiley (1898-1903) set the theme for it when he stated that he hoped it would provide work opportunities for those who could not acquire them elsewhere.[37] Carrie availed herself of each opportunity. She began to attain the skills for a good job and she opted to finish her high school work in a setting that afforded better instruction.[38]

Her age of 15 at the time of enrollment, however, was not unusual as it would not be until two years later in the 1905-1906 school year when students entering the university would be required to have completed high school.[39] Rather those younger students were entered as either freshmen if they were pursuing a bachelor’s degree or as “first year” if they were pursuing a certificate in a shorter course such as stenography in the School of Commerce. Preparatory School students were not similarly classified but referred in some years as first, second or third preparatory students.

Carrie’s U.W. transcripts are missing from those retained by the U.W. American Heritage Center. However, looking at the available information, it is apparent Carrie was working to attain three goals: finish her high school course work, prepare for future employment as a stenographer and follow her dream of being an accomplished musician. Her exact course work and status is a bit difficult to sort out.

Three sources give partial details. The first is the official publication of the university, the Melange, a combined course catalog and student directory, which lists her as follows:[40]

1903/04 "First Year" in School of Commerce (studying stenography).

1904/05 "Second year" School of Commerce and as freshman School of Music.

1905/06 School of Commerce under category "Special and Irregular" [41]

1906/07 School of Commerce under category as “Special and Irregular.”

and School of Music as sophomore.

1907/08 School of Music as sophomore.

Required coursework in the School of Commerce was listed in the Melange and included commercial arithmetic, shorthand, penmanship, typewriting, bookkeeping and commercial law

Her studies in the School of Commerce would lead to the awarding of a certificate in stenography on 22 June 1905. A headline article on page one in the Laramie Boomerang detailed the 15th commencement ceremony in the university auditorium. Carrie was one of six students who received certificates from the School of Commerce, two in bookkeeping and four in stenography. Carrie would continue her studies in the School of Commerce even after receiving her certificate, taking additional classes to strengthen her future employability.

The second source of information was her 1905 Howard University “Certificate of Applicant for Admission.”[42] It recorded the classes Carrie took in the Preparatory School by annotating them with the term “high school.” They were: grammar, composition and rhetoric, classics, history of English literature, German, algebra and civil government. Combined with the classes in the School of Commerce, she clearly obtained a very well rounded education which would afford her the training for successful career.

Music was a keen focus for Carrie at the University of Wyoming. It is odd that there is no mention of music courses on the Howard University application. Even though a place for music classes was not listed separately on the form, there was a space for entering “other subjects.” Perhaps it was because the form stated that it was prepared by the “Commerce Department University of Wyoming” that the person filling out the form simply chose not to list those music courses.[43]

Her music studies were confirmed, however, by a third source. It is found in a letter sent on 20 September 1941 by U.W. registrar Ralph McWhinnie (likely to Columbia University) which noted that Carrie took two units of secondary music and one and one-third units of college music.[44] He also noted other courses taken which comported with the earlier application to Howard University. Clearly music was just as important for Carrie as her studies in the School of Commerce. She was listed as enrolled in the “Piano Department” of the School of Music as early as 1904 and much of what is known of her activities while at U.W. revolve around music.

Carrie’s main emphasis was on both music study and performance. Established in 1897, the School of Music at the time was under the direction of Mary Slavens Clark. A 1904 photo of Carrie and the other enrollees shows 17 students, but by 1906 the number had increased substantially and there were 10 in the piano department alone.[45] Of the 10, nine were women, all from Laramie, and there was one man from Wheatland.[46] The fact that almost all were from Laramie is not surprising. The university had no campus housing, so students were required to find it on their own and, of course, pay for it.

While at U.W. she excelled as a piano student. At least a dozen times she was noted in the Laramie papers giving public recitals. She was, for example, the featured pianist for the 20 April 1905 Laramie Arbor Day celebration playing a solo titled “The Rustle of Spring.” Arbor Day celebrations in Laramie in the early 20th century were significant events and at the 1905 celebration prominent Laramie citizens, attorney Nellis Corthell, businessman W. H. Holliday, and U.W. professor B. C. Buffum presented extended remarks. Students from the west and eastside public schools also gave brief recitations and the school board promised to plant 100 trees.[47]

Perhaps the best account of her talent came from a series of articles in late August and early September 1908 where the Boomerang detailed her final appearance before she departed for further studies at Howard University in Washington, D.C. The paper listed her entire program on page one of the 1 September issue. The program included works by Liszt and Mendelsohn and she was accompanied by the university orchestra.[48] Most noteworthy was the news carried in a Boomerang article by society page reporter Bessie Bailey Cook. Ms. Cook remarked on 29 August that “Miss Burton’s musical ability has won her many admirers and a record breaking audience is expected at her farewell performance. Several prominent society ladies are acting as patronesses for the event, which will inaugurate most pleasantly the fall amusement season.” The names of the patronesses were not given.

Shortly after her September 1908 recital at the University of Wyoming, Carrie Burton departed for Howard University to further her musical studies. She later stated that her interest in Howard was kindled by the faculty at U.W. When asked by Professor H.W. Quaintance of the U.W. School of Commerce whether she had heard of Booker Washington or Kelly Miller, she replied no. Then asked if she had heard of Howard University, she again replied no. Then Quaintance said, “We will try to get you to Howard.”[49]

It appears from the earlier application to Howard that she first contemplated leaving in 1905. She received letters of recommendation that year from the head of the School of Commerce, Charles D. McGregor, instructor Frances Meader, and Grace Raymond Hebard, secretary to the U.W. board of trustees. All testified that she was an excellent student and would do well at Howard. Why she did not go in 1905 is not clear. The issue may have been money due to her mother’s medical problems which required Carrie to work to help with the family finances.

Carrie’s 1908 application to Howard is not in her collection at the Reuther Library. However, the record shows that she must have decided in June, 1908, to reapply. The first solid indication was a glowing recommendation from Professor Aven Nelson of the U.W. Botany Department to Howard University President W. P. Thirkield dated 3 June 1908. Carrie viewed Nelson as an important influence on her life and excepts from his letter bear inclusion here.

I have known Miss Burton all her life and I can say most candidly that she is a young woman of particular merit. She has all her life shown such worthy motives and commendable ambitions that she has won the highest esteem of those with whom she has come in contact. Her musical ability is rare in the public recitals of the School of Music. Miss Burton never fails to receive an encore whether the other participants do or not. I trust that you may be able to find in your University a place for her in which she will be able to make a living while she is further broadening and deepening her knowledge and culture. She has the qualities that when properly developed will make her of rare value as a teacher.[50]

This letter, along with the others from Quaintance to Howard University President Thirkield and Professor Lulu Childers of the Howard music department, helped Carrie secure entrance to Howard and also as a stenographer in the Howard president’s office. Carrie departed for Washington, D.C. 10 October 1908.

Life after Wyoming

While the focus here is on Carrie Burton’s Laramie life, a recap of her successes later is in order. Carrie did secure the position as a stenographer at Howard and would attain a diploma from the Howard Conservatory of Music in 1913. In the interim she suffered illness, was joined by her mother in 1910 after the death of her step-father, Thomas Price, and for a while would be barely able to make ends meet. She detailed her experiences in a letter to an unnamed friend which was later printed in its entirety in the Boomerang.[51]

Carrie had trouble adjusting to her new life. “At first I did not find things as I had expected them. I was permitted to work for my board only and did not know how the other expenses would be paid. I therefore worried myself sick and was under the doctor’s care for three weeks.” Carrie went on to say that her situation improved rapidly as she was soon able to secure additional secretarial work and a position on the university’s telephone switchboard. Thereafter Carrie came to immensely enjoy her time at Howard and enjoying the culture of the capital city which opened a new world to her.

The same year she received her diploma she married Mr. George W. B. Overton, a former student at Howard and the principal of the “colored schools” of Cumberland, Maryland. Interestingly, in the 1920 census, the married couple are living apart, although both in the Washington, D.C. area. She was listed as a boarder in the District of Columbia and he a boarder in Annapolis, Maryland, where he was Supervisor of Colored Schools in Anne Arundel County. The reason for the separate domiciles is likely due to the need for adequate employment. In 1923 the Overtons, who had no children, moved to New York City where Carrie continued her studies and taught piano students.

After their arrival in New York City, Carrie entered the Juilliard School of Music (at the time called the Institute of Musical Art) and took classes nearly continually from 1932 to 1941.[52] She received both a “Diploma Piano” and an “Analytic Theory Certificate.” She also continued her non-musical studies by enrolling in Columbia University. There she received a bachelor’s degree (1947) and a master’s degree (1948). For the latter, she was enrolled in the faculties of political science, philosophy and pure science.[53] She also was, at one time, writing a dissertation for a PhD at Columbia but appears not to have finished it.

In addition to her studies she was employed in many interesting positions. Mrs. Overton served as a stenographer for the NAACP from 1924-28; executive secretary to Julian Rainey, head of the "Colored Division" of the National Democratic Committee for the elections of 1932, 1936 and 1940; and in secretarial positions with Howard University, Vanguard Press, and the Community Church of New York City.[54]

Carrie also made a concerted effort to study the roots of African American music. Her most notable accomplishment was her composition incorporating two African folk songs, “Dat Lonesome Stream” and” Da’s All Right Honey,” which was played at a concert of original compositions at Juilliard on 24 May 1940. The performance was hailed a success and Carrie made recordings and submitted them to Alan Lomax at the Library of Congress in November of that same year. Carrie would state that the songs were “collected by” Lomax when in fact they were not entered into the collection and he noted that he felt the tempo was wrong. Lomax’s criticism should be tempered as he admitted that he had “little understanding” of the genre.[55] Carrie also continued to teach piano students and was editor of a work on West African music. Unfortunately, no known recordings of Carrie’s compositions have been preserved.

Carrie did not forget her ties to Laramie and returned for a visit in 1921. The journey to the West was likely due to the illness of her father, John Burton. Local papers noted that she had been in Colorado Springs to “meet” her father and records in that city note that he died later that year.[56] This is probably the first time she had met him, as he does not appear in any accounts of her early life. The paper did not give any details of the meeting, how it came about, nor what Carrie did or where she stayed after she traveled on to Laramie.

Her next visit to Laramie would be nearly 40 years later. She returned to Laramie with her husband George for the 1960 University of Wyoming Homecoming festivities. Her presence was reported both in the Wyoming Alumnews and the Laramie Daily Boomerang. The Boomerang article detailed her life in New York City and noted that she had continued her musical endeavors and was involved in numerous organizations. Most noteworthy was an award from the Amsterdam News “for courageous endeavor to live above the common level of life.” While in Laramie it was reported that she would stay at the home of college classmate and childhood friend, Miriam Corthell Moreland.[57] However, records from the U.W. Alumni Association show that she and George stayed at the Circle S motel. The discrepancy is not explainable. After returning to New York City, Carrie’s husband George died on 24 October 1964.

While that was Carrie’s last visit to Laramie, she would be enlisted in 1971 by U.W. Professor Robert Burns in an effort to save Laramie’s Ivinson Mansion from demolition. The exchange began with a phone call from Carrie to Burns asking if he could find a picture of the little white, one story house she had lived in as a child at the corner of 9th Street and Ivinson Avenue (subsequently demolished). It is likely that she contacted Burns because he was involved with the Laramie Plains Museum Association and the Albany County Historical Society and was a member of the same Methodist church that Carrie attended while in Laramie. Carrie stated that she kept apprised of events in Laramie by subscribing to the local paper so she knew of the community’s effort to save the mansion. [58]

In the course of the exchange it became known to Burns that Burton Overton had been employed by the Ivinsons, first as a girl working in the mansion’s gardens and later as a stenographer and pianist for Mrs. Jane Ivinson. Burns then inquired if she would write an article about her experiences vis-à-vis the mansion and her dealings with Mrs. Ivinson. Carrie agreed and forwarded a short undated, typewritten article to Burns titled “The Lady in the Ivinson Mansion” (received by Burns on 19 January 1972).

In the letter Carrie explained how her talents moved her from the garden work into the mansion. Mrs. Ivinson enquired if Carrie could write well and upon a positive reply asked Carrie to write out from dictation some letters for her. She did so well that it led to further employment as a stenographer for Mrs. Ivinson. Carrie’s ability at the piano came to Mrs. Ivinson’s attention and likely led to the sponsorship of the 1908 fund-raising recital. It read, “One day I found myself playing on the upright piano in one end of the spacious dining room. I was auditioning for the famous pioneer dinner.” The audition proved to be satisfactory and Carrie was rewarded when “Mrs. Ivinson sponsored me in my own piano recital in the University auditorium to pay my travel expenses to Washington D.C.”

The communication with Burns also provided information on her interaction with Laramie’s wealthiest family. Mrs. Ivinson was the wife of Edward Ivinson, the most prominent banker in town. Carrie stated that “From these personal contacts with Mrs. Ivinson, I concluded that she loved the little people who could not help themselves.” She went on to say, “She was a stately looking woman who could smile more often than people thought.”

Burns and Carrie would exchange a few more letters, but she failed to respond to a letter he sent on 23 January 1972 thanking her for the article. A month later Burns received a phone call from one of Carrie’s piano students informing him she was in the hospital. In early March, Carrie’s neighbor, Mrs. Emma Peterson, wrote to Burns that Carrie was seriously ill and still in the hospital.

Over the course of the next few months, Burns unsuccessfully tried to secure an honorary U.W. degree for Carrie Burton Overton. Despite polite answers from U.W. President William Carlson and Dave True of the board of trustees, no action was ever taken. Sadly, Burns was informed by Mrs. Peterson in November that Carrie was very ill and in a “malignant condition” and was in the Hayden Manor nursing home in New York City. That would be the last Burns heard from New York City.

Carrie Burton Overton passed away in December 1975. From all accounts, she led an enormously eventful life, succeeding beyond any childhood dream. She should be remembered not only for her musical talents but also the way she persevered in the face of poverty and discrimination. It is fitting that in a 5 December 1942 Laramie Daily Bulletin article titled “Clippings Reveal Climb to Success of Former Student,” Carrie Burton Overton said, “In all these things I have tried to repay the good people of Laramie for the faith they had in me.”

By Kim Viner

Bibliography

Buffum, Burt C. papers. Collection 400055. American Heritage Center, University of Wyoming.

Burns, Robert Homer papers. Collection 400002. American Heritage Center, University of Wyoming

Clough, Wilson Ober. A History of the University of Wyoming, 1887-1937. Laramie, Wyo.: Laramie Print. Co., 1937.

Dale, Harrison Clifford. A Sketch of the History of Education in Wyoming. Cheyenne, Wyo: State of Wyoming, Dept. of Public Instruction, 1917.

Guenther, Todd. “The List of Good Negros. African American Lynchings in the Equality State.” Annals of Wyoming, Spring 2009.

Hardy, Deborah. Wyoming University: The First 100 Years, 1886-1986. Laramie: University of Wyoming, 1986.

Larson, T. A. History of Wyoming. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1965.

McWhinnie, R. E. papers. Collection 400054. University of Wyoming American Heritage Center. University of Wyoming.

Noble, Robert F. The College of Education: 72 Years of Teacher Preparation for Wyoming's Schools. Laramie, Wyo: University of Wyoming, 1986.

Overton, Carrie Burton, Interview by Philip P. Mason, LOH002299. Walter Reuther Library, Wayne State University.

Overton, Carrie Burton papers. Collection UP000340. Walter Reuther Library, Wayne State University.

University of Wyoming. The Wyoming Student. Laramie, Wyo: Students of the University of Wyoming, March 1907.

Wyoming Newspapers. Wyoming State Library. http://newspapers.wyo.gov.

Wyoming State Teachers' Association, and Wyoming State Teachers' Institute. The Wyoming School Journal. Laramie, Wyo: Wyoming State Teachers' Association, vol III, no, 3, 1907.

Carrie Burton undated. Likely circa 1913. Walter Reuther Library. Used with permission.

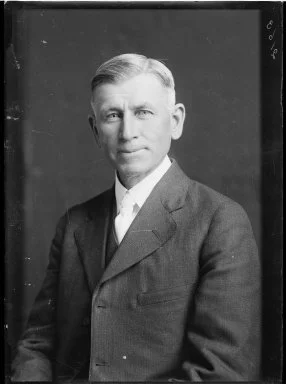

Aven Nelson. Courtesy American Heritage Center

Carrie Burton Overton and George Overton at UW 1960 Homecoming Dinner. Also shown from left: Miss Bessie Wallis, Mrs. Laura Breisch Holliday, Mrs. Evelyn Corthell Hill and Mrs Wilburta Cady. Walter Reuther Library. Used with permission.

Carrie Burton 1904 Music School Class. Mary Slavens Clark center. Courtesy U.W. American Heritage Center

[1] Alice Hardie Stevens, “Lady in the Ivinson Mansion, Author Both Fascinating Women. “Laramie Boomerang, 1 March 1972, p. 15.

[2] After consulting with Professor Ethelbert Eugene Miller of Howard University, I use the term African American throughout unless another term appears in a quotation. He felt this was best when writing for a contemporary audience, despite other terms that may be used in current and historical sources.

[3] Figures reported in “Census,” Laramie Republican 29 October 1901, p. 3, http://newspapers.wyo.gov/ accessed 25 October 2015. On the original form her “color or race” was recorded with the letter “b.” All Wyoming newspaper references though 1922 are from the Wyoming Newspapers website.

[4] The assistance of Lynne Sadler, along with Clint Black and Betsy Bress in researching Carrie’s life is greatly appreciated.

[5] Carrie’s oral history, Carrie Burton Overton Oral History, LOH002299 p. 21 held by Walter Reuther Library, says that Katie moved to Denver and then Cheyenne with her “white family” and then on to Laramie at an unknown date. Bennie Carroll’s 1900 obituary, Laramie Boomerang 18 July p. 2, states Katie arrived in 1887. I have chosen to use the published, contemporaneous account.

[6] Certainty of John R. Burton’s birth date is derived from a photo in the Carrie Burton Overton Collection UP000340 Box 1, record 6615. Walter Reuther Library, Wayne State University. Email to Kim Viner from Elizabeth Clemens 28 October 2015.

[7] Burton’s criminal records are from Mrs. Elnora Frye’s database on Wyoming Territory criminal convictions. Email Elnora Frye to Kim Viner 4 February 2016.

[8] “Both Bodies Recovered,” Semi-Weekly Laramie Boomerang 23 July 1900, p. 8. The article was the story of the drowning death of Carrie’s half-brother Benny. Benny drowned in the Laramie River while swimming with friends. It is possible that Carrie’s mother told the paper that John Burton was dead to protect the family’s reputation.

[9] Burton Overton oral history interview p. 10.

[10] Price’s U.S. Army service is documented on his application for Civil War Pension which was filed on 23 May 1892. Accessed from ancestry.com/search/db.aspx?dbid=4654 on 10 November 2015.

[11] Price’s duties with the 9th provided by Lynne Sadler. Email Lynne Sadler to Kim Viner 14 June 2016.

[12] “Chewed His Face.” Cheyenne Daily Leader 20 October 1893, p.3.

[13] Boomerang 13 April 1894 p. 3. Tracing Price’s activities is complicated as there were several Tom Prices noted in the papers during the period 1880-1910.

[14] "Composer Got Music from Father; Collection Hobby from Mother." Afro-American, 16 March 1940, p.17. https://news.google.com/newspapers accessed 13 November 2015.

[15] Carrie Burton Overton Interview by Philip P. Mason. LOH002299. Walter Reuther Library, Wayne State University. Interview conducted 22 May 1969 in the Overton home at 443 W 153rd St. New York, New York.

[16] Burton Overton interview p.1

[17] Wyoming Territory passed a law in 1869 prohibiting interracial marriages. While the law against intermarriage was repealed in 1882, it was reinstated in 1913 and was on the books until 1965. The Territorial Legislative Assembly also passed a law that year which allowed school districts to have segregated schools when 15 or more students were African American. That law, thought never applied, was superseded in 1889 by the new Wyoming State Constitution.

[18] “Miss Carrie Burton to Give Recital.” Laramie Boomerang, 29 August 1908, p.4. The article may have been written by Evelyn Corthell, the daughter of the owner of the Boomerang Nellis Corthell. Evelyn was the unnamed editor after W.E. Chaplin sold the paper to Corthell. Evelyn’s sister Miriam and Carrie were classmates and good friends.

[19] “Negro Fiend Lynched by Mob at Laramie.” Cheyenne Daily Leader, 30 August 1904 p.1. The story makes for lurid reading.

[20] Todd Guenther, “The List of Good Negros. African American Lynchings in the Equality State.” Annals of Wyoming, Spring 2009 p. 8. Guenther stated that “no efforts were made to bring the killers to justice.” In fact, Judge Carpenter convened a grand jury but it failed to return an indictment, despite clear evidence of who was involved. Carpenter’s efforts were detailed in “Judge Charles Carpenter Man of Principle” by Clint Black Laramie Boomerang, 10 October 2015.

[21] The family even invited Carrie to travel to Yellowstone with them. The invitation was declined. But it clearly shows how well Carrie was regarded by the Corthells.

[22] Carrie Burton Overton interview p. 16.

[23] “Another Brute.” Cheyenne Sun Leader 27 March 1900, p. 3.

[24] “Two Boys Drown.” Laramie Boomerang 17 July 1900, p. 2.

[25] When asked in 1969 how it was possible that they lived in that nice house, she said she had no idea. Carrie Burton Overton interview p. 11.

[26] “Both Bodies Found.” Laramie Republican 18 July 1900, p.4.

[27] “Money.” Laramie Republican 3 December 1901, p.2.

[28] “Clippings Reveal Climb to Success of Former Student.” Laramie Daily Bulletin 5 December 1942. Aven Nelson was a professor of botany (among other subjects) at the University of Wyoming from its inception and served for 55 years. He also served as the university’s 10th president (1917-1922). He was a longtime member of Laramie’s Methodist Church. In a 30 January 1911 letter to U.W. President Merica Carrie gave the equal credit to the entire university faculty. Burton Collection Box 1 Folder 4.

[29] The State Superintendent of Instruction, A. D. Cook would lament that as late as 1907 that compulsory attendance laws were seldom enforced. See Wyoming School Journal, Vol III no. 3, June 1907, p. 206

[30] Revised Statutes of Wyoming (Cheyenne, Wyo. Sun Printing, 1887), Chapter 3 article 1 section 3949.

[31] F. W. Lee, “Laramie Public Schools,” Wyoming School Journal, Vol II no 9, May 1906, p. 189.

[32] This is another disconnect in the history of Carrie Burton. She also stated that she completed the eight grades then available.

[33] “Schools Open Next Week.” Laramie Boomerang 6 September 1900, p.3. It is odd that this article and the next mentioned are in the same paper. However, it was the weekly edition of the daily paper and therefore carried articles from different dates but without stating which article ran originally on which date.

[34] For a complete description of the progress of the University in the period 1896-1904, see W. O. Clough, A History of the University of Wyoming 1887-1937 (Laramie, Wyo, Laramie Print. Co., 1937), chapter V. Available on line at babel.hathitrust.org, accessed 15 January 2016.

[35] Article VIII section 15 of the 1889 Wyoming Constitution.

[36] Letter Dr. Aven Nelson University of Wyoming to Dr. W.P. Thirkield, President Howard University 3 June 1908. Carrie Burton Overton Collection Box 1 Folder 4. NOTE: The Cheyenne Wyoming Tribune reported on 27 June 1905 in a story titled “20 Graduate” that “Miss Burton is a colored girl, the first to receive a certificate from the University of Wyoming, the only colored student so far enrolled.” The statement that she was the first African American of either gender to enrolled is not true. A photograph of the 1897 Cadet Corps of the university shows an African American (unfortunately none of the cadets are identified) in the ranks. Cadet Corps, 1897. Samuel H. Knight Collection, Box 82, Negative B1-2090. Collection 400044 University of Wyoming American Heritage Center.

[37] Clough, History of the University of Wyoming. p. 72. The names of the colleges, schools and departments of the early university were changed often and following their evolution is a bit daunting.

[38] No public school in Wyoming offered a full high school course until 1909. For details of high school offerings in the period before 1909 see Harrison Clifford Dale, A Sketch of the History of Education in Wyoming (Cheyenne, Wyo: State of Wyoming, Dept. of Public Instruction, 1917).

[39] Deborah Hardy, Wyoming University: The First 100 Years, 1886-1986. (Laramie: University of Wyoming, 1986). p. 16.

[40] Melange 1903-1908. Box 61, R. E. (Ralph Edwin) McWhinnie papers. Collection 400054. University of Wyoming American Heritage Center.

[41] It is likely that for the 1907 school year Carrie was listed in the “irregular category” because of an extended absence due to acute appendicitis as reported in the Boomerang on 29 August. Other absences were caused by the need to work when her mother was incapacitated with “rheumatism.”

[42] Carrie Burton Overton Collection UP000340 Box 1, record 6615. Walter Reuther Library, Wayne State University.

[43] Carrie was also involved in a number of activities outside of the classroom while at U.W. She was an officer in the newly established Young Women’s Christian Association, holding the ill-defined position of “inter-collegiate.” She was also a member of the “girls cadet corps,” an on and off again complementary organization to the mandatory male cadet corps. Additionally, Carrie tried her hand at short story writing. In the March, 1907, issue of the Wyoming Student she published a two-page item titled “Sella,” about a girl who finds a pair of magical white slippers. Against the advice of her mother Sella tries them on and experiences a mystical journey with a “beautiful water nymph.”

[44] Carrie Burton Overton Collection. Box 5 folder 5.

[45] Burt C. Buffum papers. Item 43, Box 11. Collection 400055. University of Wyoming American Heritage Center.

[46] Melange 1906.

[47] “Arbor Day in Laramie” Laramie Boomerang 21 April 1905, p. 1. As is often the case in high altitude Laramie, the weather did not cooperate and tree planting had to be deferred.

[48] “Miss Burton Gives a Public Recital Tonight.” Laramie Boomerang 1 September 1908, p. 1.

[49] Carrie Burton Overton interview p. 14. Professor Hadley Winfield Quaintance was head of the School of Commerce 1905-1908.

[50] Burton collection box 1 folder 4.

[51] “A Laramie Girl in Washington.” Laramie Boomerang 26 March 1909, p. 3.

[52] Email Lee Anne Tuason, Juilliard School, to Kim Viner, 28 October 2015.

[53] Email Jocelyn Wilk, Columbia University, to Jonel Wilmot, Laramie Plains Museum curator, 19 November 2001.

[54] The Carrie Burton Overton collection guide with this brief biography can be accessed online at http://reuther.wayne.edu/node/1217 .

[55] Letter Carrie Burton Overton to Alan Lomax 22 November 1940. Letter Alan Lomax to Carrie Burton Overton 2 December 1940. Email Todd Harvey, Library of Congress, to Betsy Bress, Curator Laramie Plains Museum, 21 October 2015.

[56] “Former Resident Visiting City.” Laramie Daily Republican, 19 July 1921, p. 8.

[57] “Outstanding New York Leader Will Attend U.W. Homecoming.” Laramie Daily Boomerang, 25 October 1960. Burns Collection box 3, folder 13.

[58] Robert Homer Burns papers, box 3 folder 13 collection 400002. American Heritage Center. University of Wyoming. Correspondence November 1971 through January 1972. The Laramie Plains Museum purchased the Ivinson Mansion in July 1972 and opened its doors to visitors in January 1973.