Emma Howell Knight’s legacy in education: Equals that of her husband and children.

When Emma Howell Knight (1865-1928) became a widow at age 38, she was left with four children ages 2 to 12. This was not likely the way she pictured her life unfolding. Her husband Wilbur Clinton Knight (1858-1903) was just 45. No one could have predicted that after a sudden five-day illness he would die of what the doctors said was inoperable peritonitis caused by a ruptured appendix.

Move to Laramie

Emma had been a student at the University of Nebraska when she met and married Wilbur in 1890. We don’t know how many semesters she had completed, but she interrupted her education to leave for the Keystone mining area of the Medicine Bow Mountains in Wyoming where Wilbur worked as a geologist and mining engineer for the “Florence” mine. They named their first-born (in 1891) Wilburta Florence Knight, after the mine.

By 1893 they had moved to Laramie. Wilbur accepted a position as a professor in the newly formed UW School of Mines. That “school” never really materialized though teaching geology became his specialty. By 1897 he had become the Wyoming State Geologist. They entertained other UW faculty and townspeople; Emma joined the Laramie Woman’s Club and was soon secretary and then president of the organization. In rapid succession she gave birth to two more children: Samuel Howell in 1892, Everett Lyell in 1894, and then, seven years later, Oliver was born in 1901.

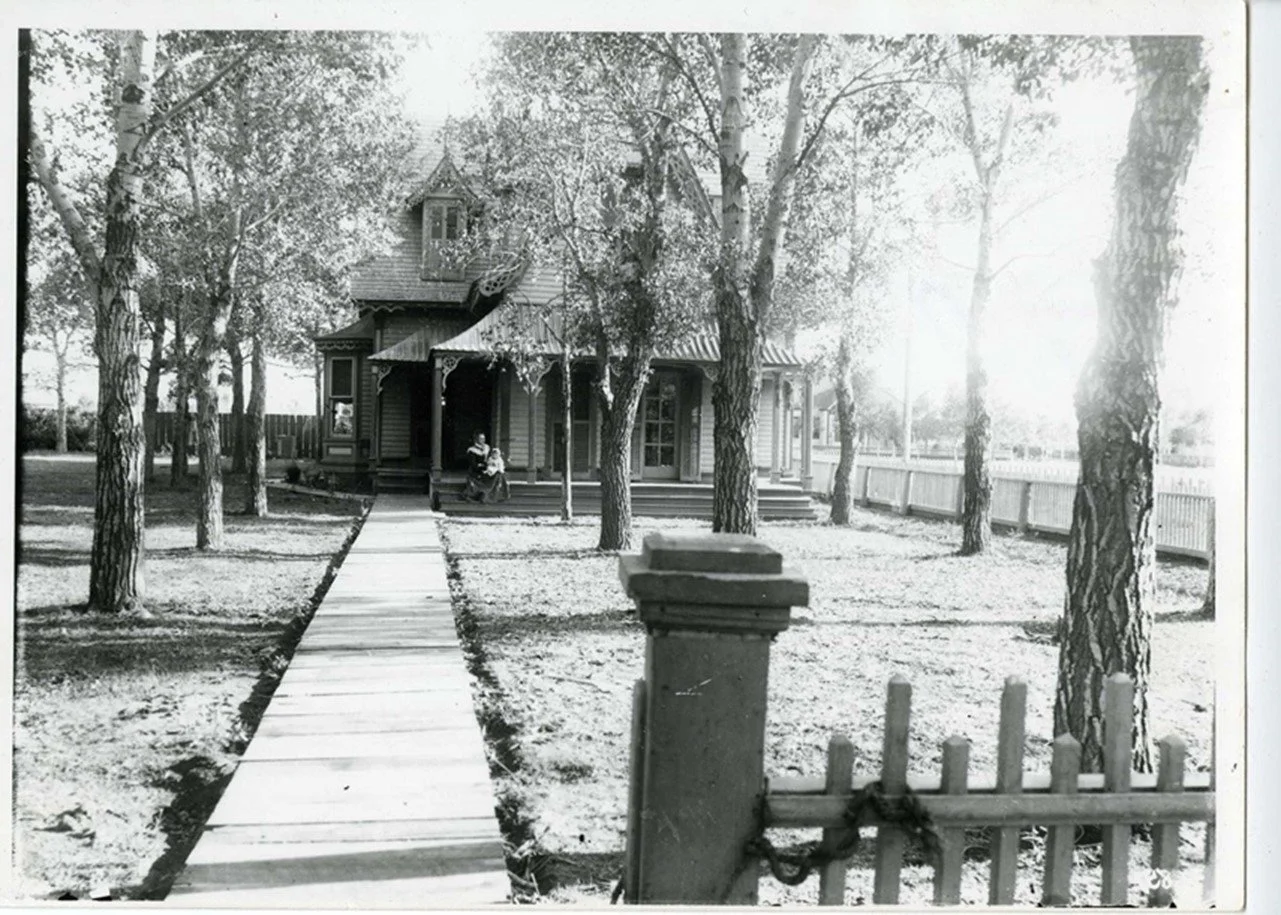

Wilbur left Emma fairly well off. In 1901 they had bought four adjacent lots on Grand Ave. including a magnificent house at 914 Grand Ave. The Gothic Revival styled house was the only one of its kind in Laramie. Some experts say that it is the only one of that style in all of Wyoming. It had (and still has) a storybook quality with tall, pointed pediments and dormers, many gables, and decorative finials. However, Wilbur died intestate.

It took over a year and a half to settle his estate through probate, with many court filings that her attorney, C.P. Arnold, saw through to successful completion. During the proceedings, the court awarded her $100 per month from the estate to care for the children and herself.

Continuing education

No doubt in those days before Social Security and widow’s benefits, Emma was concerned about how she was going to manage. She left for Lincoln, Nebraska with the children late in 1903. She was very close to her parents, the Howells, who lived there after emigrating from Canada with young Emma and their other four children. It was likely that Emma and her children became part of the Howell household, which also included Alice Howell, Emma’s younger sister, who became a professor of elocution at the University of Nebraska.

Emma enrolled at the University of Nebraska to finish the studies in domestic science (Home Economics) that she had begun and likely earned a 2-year diploma.

There must have been some speculation in Laramie that Emma would not come back. A brother, J.H. Howell, lived in Seattle at the time and passed through Laramie frequently on his way to and from his relatives in Laramie and Lincoln. He assured the Laramie Republican on Feb. 24, 1904, that “Mrs. Knight has no intention of abandoning Laramie as a place of residence but will return with the family in June.”

Superintendent and Dean

It may have been on Emma’s mind all along to enter politics, for that is what happened within four months of her return. In October 1904, she accepted the Republican party nomination to run for a two-year term as Superintendent of Schools in Albany County. She was elected that November and three more times (1906, 1908, and 1910).

Before the election of 1910 the Laramie Republican newspaper of October 19 said that Mrs. Knight had no democratic opposition for the race. The democrats had nominated someone, but that person “declared that she is not a democrat and was named without her consent or knowledge, and that she will not serve on the ticket.”

As school superintendent, it was Emma’s goal to visit all 62 rural schools in those horse and buggy days. She met that goal, though family lore says that she often piled her children into the wagon for the trip. She was also enrolled at UW during that time, working toward a bachelor’s degree.

Emma was especially concerned about developing libraries in rural schools and seeing that teachers were well-prepared. She organized a teachers’ institute, two- or three-days of in-service training for returning teachers held at the close of the school year. In at least one annual report she lamented that the frequent turnover of rural school district directors led to confusion and late reporting. At least once, the newspaper mentions that she was called upon to settle boundary disputes for the various school districts formed to educate ranch children through 8th grade.

Emma may not have finished that last term as superintendent, as in 1911 she accepted a position as “advisor to women students” at UW. Emma moved into the women’s dormitory, the newly built Merica Hall. She and the family had been living in the house at 914 Grand Ave., but the older children, Wilburta and Samuel, and a housekeeper, Arlie Mansfield, age 21, could look after the younger boys, Everett and Oliver. Most references say that she was Dean of Women at UW from 1911 to 1921, though it appears that she didn’t have that title at first.

Emma made many long trips while she was employed, giving local talks about her travels to Seattle, New Orleans, and other eastern states. She continued to be active in the Laramie Woman’s Club and was often mentioned in the newspaper as a guest at various social gatherings, particularly for luncheons in Merica Hall where students enrolled in Home Economics would plan, cook, and serve formal meals as part of their training.

Graduates with daughter

Emma Howell Knight was awarded a UW bachelor’s degree at spring commencement in 1911 and made coast-to-coast history because her children were enrolled at the same time. Daughter Wilburta also graduated with a bachelor’s degree that year. Newspapers from Delaware to California picked up the story, which said that all four of her children were enrolled at UW. Her son Oliver was only 10 at the time, but he could have been enrolled at the UW Preparatory School (Lab School) while his older siblings were attending UW.

Her second-oldest, Samuel Howell Knight (1892 - 1975), graduated from UW in 1913, following in his father’s footsteps by studying geology. In those early days, he was always referred to in the newspaper by his middle name, Howell. It may be what the family called him, but when he went on to graduate school he became “Sam” or just S.H. Knight.

He earned a doctorate in geology at Columbia University in New York City. That’s also where he met Edwina Hall and married her there in 1916. They returned to Laramie where he accepted the position his father had held as professor of geology. In 1919, his mother deeded over the splendid Gothic Revival house to Sam and Edwina.

Storybook house

Records in the county courthouse are a little unclear on just when the house was “moved” to 310 S. 10th St., very close to Grand Ave. But there is a clue in the 1928 Laramie City Directory, which gives S.H. Knight’s address as 914 Grand Ave. In 1929, three brick houses were built at the three Knight-owned lots on Grand Ave. They occupied land that previously had been the spacious front yard of the house at 914 Grand Ave. that Sam and Edwina now owned. (The three new houses have addresses of 914 and 916 Grand Ave., the third faces 10th St. so its address is 302 S. 10th St.)

Thus, the picturesque house was simply turned sideways in 1928 so that the front door faced 10th St., instead of Grand Ave. In that depression-era time when funds were short for everyone, having those three properties to sell was probably an important source of income for Sam and Edwina. Tall trees hide much of its detailing now, but it is well worth taking a look at this handsome relic of Laramie’s early days, built in 1872 when Laramie was just four years old.

Retirement

In 1921, Emma retired as UW Dean of Women. The 1920 census for Laramie shows that she had already rented a house and filled it with people, so it’s likely that she was not living in the women’s dormitory then. The location of her rental house isn’t clear from the census, but it lists 9 other lodgers with her, a widow with two children, a divorced woman with one child, a single man, and three other single women.

One retirement trip to Yellowstone ended with an embarrassing headline, “Even Women of Brains Disobey Park Rules,” as published in the Northern Wyoming Herald of Cody on July 12, 1922. Apparently, Emma was feeding a bear as tourists then were wont to do, and it bit her on the hand. “Mrs. Knight had presence of mind enough not to move” said the paper, so the wound was not serious.

Emma was only 56 when she retired and had plenty of energy to tour around with her sister Alice and other friends. However, in 1928 she had an emergency appendectomy and died a few days later from peritonitis, coincidentally, the same ailment that had taken her husband’s life 25 years earlier.

Legacy

Jane and David Love wrote a fine tribute to Emma’s son Samuel Howell Knight, when he died in 1975. They also paid a tribute to his mother, calling her a “well-educated, wise woman who encouraged her daughter and sons to develop broad interests and to receive a college education.” Geology was Sam’s passion and her other two sons followed in related fields of petroleum development. Her daughter Wilburta became a schoolteacher in Colorado, but married Laramie businessman Charles Earl Cady and remained in Laramie with him and their two children throughout her life.

When a new women’s dormitory was built on the UW campus in 1941, it was given the name Knight Hall, and dedicated to the memory of Emma Howell Knight. That provided a dilemma for the UW trustees when they wanted to name another building for her distinguished son Samuel Howell Knight.

Obviously, the trustees decided the honor was so highly deserved by both, that they would tolerate two “Knight” buildings on the campus. The full name of the Geology Building at UW is now the S.H. Knight Geology Building. In front of it stands an 18.5-foot-tall Tyrannosaurus rex copper sculpture that was a retirement project of “Doc” Knight, who taught himself sculpturing techniques to build it. In 1999 he was selected posthumously as Wyoming’s Citizen of the Century.

Another coincidence

Readers may notice that “Knight” is also my name. My husband Dennis H. Knight joined the UW Botany Department faculty in 1966 and besides courting me, around 1967 he visited with Samuel H. Knight about the possibility of their being related. They concluded that they were not.

However, in retirement about 40 years later, further genealogical research by Dennis showed that there is a relationship. Their ancestors were brothers 13 generations ago - their father was the Keeper of the Prison in Newport, RI (in the mid 1600s). There was a hint of some previous misbehavior on the part of that father, who had left New Hampshire in a hurry before anyone could bring him to account alleged theft. So, to clear their name, there is a “who done it” for the next generation of Knights to tackle.

By Judy Knight

Source: both photos Laramie Plains Museum

Caption: Emma Howell Knight, taken around 1905 when she was Superintendent of Schools for Albany County. Photographer: E.N. Rogers of Laramie.

Caption: Emma Howell Knight lived in this house at 914 Grand Ave. for 10 years, from 1901-1911. She is pictured on the front porch with her youngest child, Oliver. Then she moved to a woman’s dormitory on the UW campus for a number of years and gave the house to her son S.H. Knight in 1919--he lived in it nearly all of his life. It was built in 1872, and was turned in 1928 so that it now faces 10th St. The photo was taken on a glass plate negative by her husband, UW geology professor Wilbur C. Knight in 1901.