The Great Tribulation of 1870

Suppose that on one of Laramie’s lovely June days, you’re out in the garden pulling weeds when a man (has to be a man) appears, introducing himself as Assistant Marshal with the U.S. Census Office. You’re not surprised—word spreads quickly in this town.

He proceeds to ask a seemingly interminable series of questions, required by law, for every person in the household: name, age, sex, and color; occupation; property, bonds and other valuables; and more. Finally, is anyone illiterate? insane? a pauper?

But that was 1870. The U.S. census is no longer a Great Tribulation (from Latin ‘tribulum’—a threshing board with sharp points). The 2020 census now underway is short, easy, confidential, and, if done right, safe!

Enumerating the people

Article 1, Section 2, clause 3 of the U.S. Constitution (ratified in 1788) directed Congress to count the residents of the young country in order to fairly apportion congressional representatives and direct taxes among the States. “The actual Enumeration shall be made within three Years after the first Meeting of the Congress of the United States, and within every subsequent Term of ten Years.”

Shortly before the second session ended, the Census Act of 1790 was signed into law. The first “enumeration of the inhabitants of the United States” began that August, overseen by appointed U.S. Marshals. Assistant Marshals were hired to do the actual enumeration.

An estimated 650 enumerators—better known as census-takers—visited every household in the country, making six inquiries at each: What is the full name of the head? Provide number of persons in each of five categories: free white males 16 years of age and older [to assess industrial and military might]; free white males under 16 years; free white females; other free persons noting sex and color; and slaves.

Confidentiality apparently was not an issue in 1790. Census-takers posted their results in “two of the most public places ... for the inspection of all concerned.” The “aggregate amount” was sent to the President. But when George Washington read that the population of the United States was only 3.9 million, he wasn’t happy. He was sure it was larger.

Washington wasn’t alone in his opinion. For the first century of its existence, the most common complaint fielded by the Census Office was undercounting. A growing population meant more federal representation and funding, and was a source of civic pride. Community members looked forward to the results of a census, and objected loudly when they found numbers too low.

Country grows, census evolves

For the second census, some 900 enumerators counted 5.3 million residents—a 35% increase in ten years. In addition to questions asked in 1790, they recorded number of white males and females by age: under 10, 10 to 15, 16 to 24, 25 to 44 and 45 to “the utmost boundaries of life.”

Questions about manufacturing and industry were added in 1810, but dropped twenty years later due to obvious inaccuracies. They reappeared with the Census Act of 1840, which directed the Census Office to determine "the pursuits, industry, education, and resources of the country.” That year, 28 clerks processed information collected by 2167 enumerators to produce a report 1465 pages. The nation’s residents totaled 17.1 million.

The country continued to grow rapidly in area, population and number of census-takers. In 1860, 4417 enumerators counted 31.4 million residents, asking about taxes, schools, crime, wages and property values, among other things.

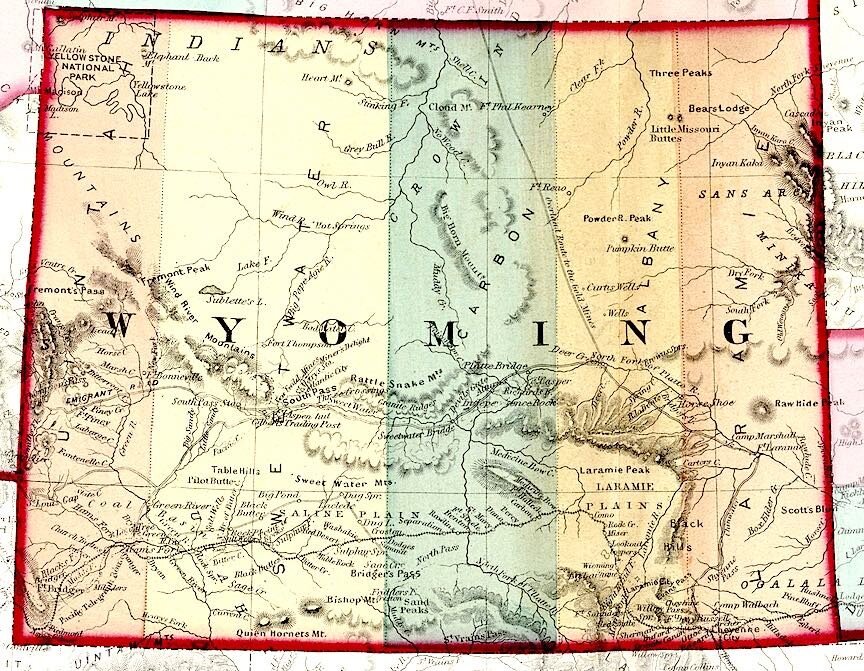

The 1870 census was a milestone. Just five years after slaves were granted freedom, it was the first to collect the usual personal information for black residents. It also was the first to include Wyoming Territory, which had been part of Dakota Territory until 1868.

Counting Albany County

In May of 1870, news of the upcoming census appeared in the Laramie Daily Sentinel. “Census-takers get two cents for every name taken, ten cents for every farm, fifteen cents for every productive establishment of industry, two cents for every deceased person, and two per cent of the whole amount for names enumerated for social statistics, and ten cents per mile for travel.” They would be paid only after they completely enumerated their area, and their forms were accepted.

The Sentinel also reported disturbing news. Even though women had the right to vote in Wyoming, they would not be not allowed to work as census-takers!

Editor James Hayford denounced the policy, using this excerpt from an Iowa newspaper: “By a recent decision of General Walker, Superintendent of the Census, the women can furnish this country with its children but are not to be permitted to count them ... The old ruling that you mustn't count your chickens before they are hatched, will take on the new form that women must not count their children even after they are born.”

True confessions

Now back to the garden, on that lovely June day 150 years ago. After the census-taker introduces himself (actually, you already know him; he’s your neighbor, Walter Sinclair), he sets up his “secure portable inkstand, good ink, and pens,” and pulls out a form and blotter supplied by the Census Office.

Sinclair makes it clear that you are required by law to answer census questions, but follows the guidance of the Instructions to Assistant Marshals: “Make as little show as possible of authority. ... approach every individual in a conciliatory manner; respect the prejudices of all; adapt inquiries to the comprehension of foreigners and persons of limited education; and strive in every way to relieve the performance of [your] duties from the appearance of obtrusiveness.”

Contrary to the 1790 practice, he emphasizes that information will “be treated as strictly confidential.” Indeed, the instructions state: “no graver offense could be committed by a census-taker than to divulge information.” Anyone suspected of such an offense will be investigated, and if found guilty, released with no pay.

There are twenty questions in all, to be asked for each member of the family. A family might be a solitary inhabitant, or the many residents of a boarding house or prison. For the purpose of the census, if people “live together under one roof, and are provided for at a common table, there is a family in the meaning of the law.”

Sinclair records name, age, sex, color, occupation, and much more, regularly drying his entries with the blotter. He uses his own judgment regarding age. “The Assistant is to obtain exact age wherever possible; otherwise, a best estimation will be made. ... Where the age is a matter of considerable doubt, the Assistant Marshal may make a note to that effect.”

The most sensitive information is addressed last. Which members of the family read? Write? Two questions are required because “Very many persons who will claim to be able to read, though they really do so in the most defective manner, will frankly admit that they cannot write.” Finally, are any members “deaf and dumb, blind, insane, or idiotic; a pauper or convict”?

Sinclair then reads back the information he recorded, correcting any errors. As you return to weeding, he moves to the next dwelling. He continues as long as weather and light allow. That evening, he transcribes (by hand) two copies of the day’s completed forms, each containing information for 40 residents. In all, Sinclair filled and submitted 52 forms.

On lines 4-6 of his third form, Sinclair entered information about his own family. He and wife Anna were both 32 years of age; son Walter Kirby was 7. All three were born in Ohio, suggesting they were relatively recent arrivals to the Territory. Sinclair gave his occupation as “Ranchman” but he was better known as Deputy Sheriff of Albany County. The Daily Sentinel characterized him as an “energetic thorough officer and a terror to evil doers.” Perhaps this encouraged residents to respond promptly and honestly.

Results? Sorry, you’ll have to wait.

For the 1870 census, 6530 enumerators were able to cover the country in five months, but it took 428 clerks two years to tabulate and analyze the information. Each form had to be manually transcribed onto a grid with columns and rows representing the various types of information collected. These were then analyzed “visually.”

The final report—3473 pages of mostly tables—was published in 1872. The U.S. population was just under 39 million, ten times that of 1790. Wyoming had 9118 residents, 2021 of which lived in Albany County. The population of Laramie was 828.

The amount of information gathered in 1880 was immense, requiring seven years to process. If this trend had continued, soon the previous census would still be underway when the next started! Fortunately, an electromechanical tabulator invented by former census employee Herman Hollerith saved the day. For the 1890 census, processing was reduced to ‘just’ six years, though the population had grown by 25% and many more questions were asked.

Hit Send and be counted

Thanks to today’s wonderful information technology, the U.S. Census Bureau conducts surveys on many topics every year, such as education, income, occupation, housing and emergency preparedness. But it remains best known for the decennial census, the 24th of which is currently underway.

Your household should have received by mail an “invitation” from the Census Bureau, asking you to respond in one of three ways: online (new this year), by phone, or on paper. The list of questions is short, and not all that different from 1790—number of residents; sex, age, race, relationship of each; and whether residents are of Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish origin. Because the census counts every resident, as it has since it was created, you are NOT asked whether you are a U.S. citizen (more information at 2020census.gov).

Those who don’t self-respond will have a census-taker knocking at their door. That would be a shame. Online, phone and mail are more efficient, more accurate, much cheaper, and in coronavirus times, much safer. If you haven’t already, please self-respond and be counted!

By Hollis Marriott

Source: Walling, Gray, Lloyd & Co. 1872, Atlas of the United States (public domain)

Caption: Wyoming Territory circa 1870 showing only five counties, Albany County second from right

Source: public domain

Caption: Census-taker, ca. 1870, original source unknown.