Stereographs: Victorian Popular Entertainment Important visuals in the days before television

In today’s day and age, it takes very little effort to transport ourselves somewhere else. Turn on the travel channel and you can see other countries, peoples and their cultures, hear different languages and see exotic locations. Watch a sci-fi movie and be transported to the future or a parallel universe.

Before TV

Television and the virtual world are often taken for granted. Many of us grew up with these devices as a part of our society and culture. During quarantine many indulge in these or to learn more through the news.

Before television, people had to be a bit more creative for entertainment. Of course, by 1877 the Edison Phonograph made music accessible without the need of a live musician; and conversation and group games have a long history in terms of creating enjoyment, or one could simply pick up a book.

In 1851 the Victorians discovered a way to take the viewer to a different place. It may not seem all that spectacular to us today with virtual reality and other interactive medias but for the Victorians it was truly a life changing experience. The stereograph: a device used to view a photograph in three dimensions was produced for anyone who could afford them.

History

Credit for the invention of the stereograph is often given to Sir Charles Wheatstone in 1832 though others claim that James Elliot, a mathematician of Edinburgh, conceived the idea earlier.

Wheatstone’s device used hand drawings because photography was in its infancy. This device had two mirrors at 45°angles which reflected the same image off to each side. When a picture was viewed in the device, it appeared three-dimensional.

David Brewster, Sir Wheatstone’s rival, is credited with suggesting the device use lenses in 1849. The lenses allowed the device to be much smaller (Wheatstone’s device covered an entire tabletop) and capable of being held in one hand.

Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr. created the handheld streamline device that we now associate as a stereoscope in 1861. He did not patent his design, so other companies produced similar versions. The Holmes version was much cheaper to reproduce on a large scale.

The double imaged cards or stereo cards used in the stereoscope were possibly created by Holmes, but credit is also given to Louis Jules Duboscq, French instrument maker and photographer. Duboscq is credited with the creation of the stereo card daguerreotypes used at London’s1851 World’s Fair where Queen Victoria herself expressed enthusiasm for the invention. A new market was created almost overnight.

Demand for photos

Photographers began travelling the world to capture images to sell as stereo views. According to the London Stereoscopic Company LTD website, the London Stereoscopic Company founded in 1854 is an example of an early European photographer’s studio. It produced only stereoscopic views. They created thousands of images of unusually high quality that are highly collectible today.

Subjects from European companies include famous landmarks such as castles and battle sites, but also of the wealthy who posed for portraits. Exotic landscapes such as the Egyptian pyramids and views of other cultures were popular.

Stereographs were used in America to record the Civil War but did not reach the height of popularity until the 1880s. Photographers around the country began producing the views to sell, which included landscapes and newly created frontier towns of the West. Also, historic landmarks and places and artifacts to do with our unique democratic government were popular themes.

American stereo view companies sprang up including the American Stereoscopic Company (1850s-1915), B. W. Kilburn & Co. (1865-1910), Underwood & Underwood (1881-1920), Keystone View Company (1892-1963), and many others. Famous photographers produced views of their own images including famed photographer of Yellowstone (including Colorado and Wyoming) William H. Jackson and Carleton E. Watkins who photographed Yosemite.

Mass markets

The 1902 Edition of the Sears, Roebuck Catalogue advertised stereographs priced at 24 cents. The advertisement indicates there were cheaper versions available, but “we cannot consciously recommend them to our customers,” presumably due to poor quality.

The stereo views sold for as little at 36 cents for a dozen (black and white) and the highest quality (usually in hand-painted color) sold for as much as 95 cents for a dozen. Topics include the World’s Fair series, American picturesque series, a comic series, Yellowstone National Park and Yosemite Valley series, sporting views, religious subjects, and the Spanish-American War of 1898.

It was quite expensive and cumbersome to travel during the nineteenth century. Only the wealthy could afford the luxury. The stereograph offered an alternative to mostly the middle class. These devices were often displayed and used in Victorian drawing rooms and parlors as a form of entertainment for guests as well as family members.

Historical record

Photography was a new art medium but was quickly recognized as a form of recorded history, thus lending another purpose as an educational tool. Secondly, this new record keeping was unique in that it portrayed exactly what the photographer saw rather than a written description of the writer’s perspective. This does not mean that photography is not biased, but it was an improvement to previous methods.

The emergence of the stereograph coincided with changes in education. Previously, educators used memorization, recitation and writing as methods for learning. Stereographs offered the use of sight as an additional layer with the intention of “delivering vivid and memorable object lessons by virtue of the three-dimensional images it simulated,” says Meredith A. Bak in “Democracy and discipline: Object lessons and the stereoscope in American education, 1870-1920,” published in 2012.

Educational tool

Underwood & Underwood and Keystone Views Company were able to transform the stereoscope into an educational tool rather than a leisure object. Through marketing and repackaging, the stereoscopes popularity soared in the United States.

Themed box sets with 100 related views were advertised with maps and other interpretive material (sold separately!) for use by the educator and to a smaller extent, the general consumer. In the early 1900s manuals and user guides were written by various individuals on how to receive the most benefit from these boxed sets.

Though the interpretive materials were meant to create greater versatility in an educational setting, Bak goes on to describe how the materials could be limiting in scope in that the ways the images were described offer little in terms of objectivity and cultural relativism. In some cases, the examples provided were contradictory.

Important artifacts

Despite the social implications of problematic materials, the stereo views are extremely valuable to historians and the institutions that keep them. Some views record civilizations that have since gone extinct and landscapes that have changed. They show technologies that have been replaced with newer processes and help us today understand how our predecessors viewed the world.

Bryan Ricupero of University of Wyoming’s Digital Collections along with Glory Taylor, former Library Specialist in Emmett D. Chisum Special Collections, partnered with us at the Laramie Plains Museum in a project to digitize selected stereograph views held in both collections.

We applied for a grant in 2018 and the coalition was awarded funding through the Wyoming State Historical Records Advisory Board (SHRAB).The grant provided funding for the scanning, description, creation of metadata and editing of our comprehensive collection of stereographs.

Included in the collection are photographs from well-known nineteenth century photographers William H. Jackson, Charles R. Savage (photographer of towns and landmarks along the Union Pacific RR, Central Pacific RR, and Utah Central RR) and others.

Laramie photographer George W. McFadden is also represented in the collection. Scenes of Laramie are present, primarily different views of Second Street. Most scenes represented in the collection are of Yellowstone National Park.

Bryan Ricupero says that “Work continues on the stereograph collection through a second year of [Wyoming] SHRAB funding. The project is focused on providing users augmenting viewing applications for the collection.” Sophie Miller, Library Specialist in Emmett D. Chisum Special Collections, is working with Ricupero in the second phase of the project. The objective is to be able to show these images in the way they were intended to be seen, in three-dimensions.

By Konnie Cronk

Source: Laramie Plains Museum

Caption: Jeffrey’s Bistro of Laramie currently occupies this building at 123 Ivinson Ave., shown here when it housed a drug store (and possibly a barber shop) before the building’s third story had been removed. Smoke in the distance is from the Laramie Rolling Mills, which employed about 300 men 24/7. Photo dates from 1910 when the mills burned down, or earlier. Stereographs like this can be seen at https://mountainscholar.org/handle/20.500.11919/3844

Source: Laramie Plains Museum

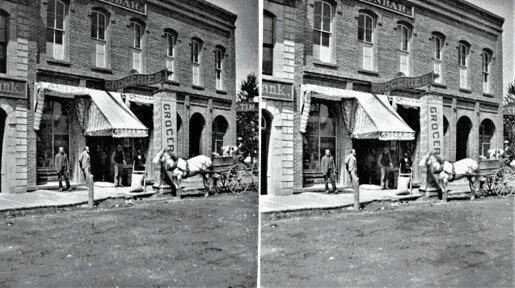

Caption: 202 S. 2nd St., Laramie when it was a grocery store operated by A.S. Peabody, image from around 1879, probably taken by Edwin Peabody of Salem, Mass. He was the brother of the store owner. The building still stands, now the Crowbar & Grill.

Source: Courtesy image.

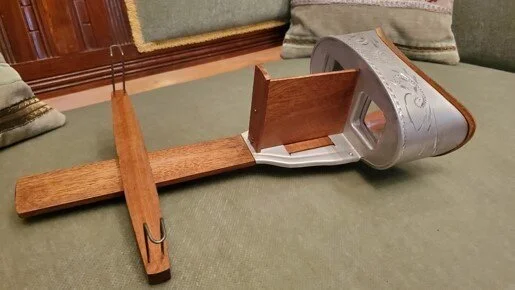

Above: Stereopticon viewer at the Laramie Plains Museum, showing the wooden slider holding the card on which the photographs are printed. Viewers move the cardholder forward or back to position it clearly for their eyesight to reveal the 3D image.

Below: Detail of engraving on the metal viewer.