Sporting Houses; Did Laramie Tolerate them? Yes indeed!

Since the days of Biblical Mary Magdalene (and before), there have been women who were willing to partner temporarily with men who were not their husbands.

Starting with its founding in 1868, Laramie was well known along the Union Pacific Railroad for its active red light district. But that was extinguished abruptly in 1956. Learn why on a walking tour of Laramie that will feature the former locations of Laramie’s “bawdy houses.”

Tour guide

Leader of the tour will be former Laramie mayor Germaine St. John. She grew up during the 1940s and 50s in the final days of the bordellos. She says the women could easily be spotted in the daytime as they shopped downtown. “You could tell who they were because they were so well dressed,” she says. “The rest of us didn’t have the money for nice new clothes in those days.”

“And they were good tippers,” St. John adds, without a trace of irony, quoting a girlfriend who was a salesgirl at a women’s wear store. “Who ever heard of tipping a salesgirl in Laramie?” she asks. But her friend knew her customers by name and knew what alterations were needed. “That was when stores really gave service,” St. John recalls.

Their business escalated in the 19th century, according to Russian-born Emma Goldman, who wrote a 1917 article about the profession in America. Goldman is quoted by Carol Bowers in her 1994 UW Master’s thesis titled “Less than ladies, less than love…” There were several reasons for the rise in bordellos, among them rapid industrialization, which brought hordes of single men from the countryside into towns and cities where more anonymity was possible. In small towns, everyone knew everyone else’s business.

Poverty

Industrialization also brought a level of poverty that had been unheard of in previous times. If there were other attractive options, most women would probably not choose the path these women chose. Even if not born to poverty, societal norms forever tainted a girl who was seduced and “ruined” by a man.

Such was the case for 12-year old Bridget Gallagher of Laramie. She was essentially kidnapped and taken to mining towns by a scoundrel. Then when he dumped her back on the streets of Laramie she was unaccepted, though we know she stayed in touch with her Laramie parents by what was reported at the time of her death. The notice of her suicide at age 19 in the February 1, 1890 issue of the Laramie Sentinel is an example of scabrous writing by moralistic editor J. H. Hayford. He concluded the anonymous (but unmistakably his) story with the line: “in sympathy to her old grayheaded father and mother we make no comment on her wasted life and tragic death.” Prior to that he said Bridget was “well known to the police of Laramie and Cheyenne.”

Women’s roles

Wives and maiden ladies were to be pure, chaste, and submissive. Until the 1800s, single, widowed and married women could become domestic help, schoolteachers, missionaries, milliners, poets, writers, seamstresses, or nurses. That was about it. Custom demanded that if they were married, they were to stay home raising children and engaging in social activities with each other. If single, they could spin yarn and weave homespun cloth. This is oversimplified, but not far off the mark.

All this began to change through the 1800s when a few courageous women joined professions that had been exclusively men’s. This was easier in the frontier west than it was in the east, since often daughters had to take on men’s roles on the farm and ranch; they began entering previously all-male occupations. But they had to endure being thought of as “loose women” because they worked with men. Moreover, industrialization in the textile industry made homespun goods obsolete; “spinsters” were no longer appreciated in the home. If there weren’t a supportive relative or friend, they had nowhere to turn.

The demimonde

So what were women on the fringes of society to do? There was no social security, no widow’s benefits to sustain them. They were suspected of not being pure and sometimes earned the epithets thrown at them. “Loose” was the nicest term to describe them; among the others were “soiled dove,” “fallen angel,” “Magdalene,” “lady of the night” and “trollop.” They existed on a totally different social plane than other, more respectable women. They fell into the “demimonde,” an alternate and some thought degenerate lifestyle.

Laramie was no different than many other frontier towns in providing opportunities for both types of women, the chaste and pure but highly capable as well as those capable in a profession that was often viewed by city fathers as an evil necessity.

The “Hell on Wheels” rowdies that crowded into Laramie in 1868 included gamblers, saloonkeepers, waiter girls and dance hall girls. The women in this group were part of the demimonde. Kate Boyd and Kate Allen were identified in Laramie’s 1870 census directly with the “p” word under “occupation.” Those census takers were nothing if not thorough.

“License”

From its earliest days, Laramie City government passed ordinances forbidding “bawdy houses.” However, the punishment was minor—a fine that could be as low as $10 a month, according to Bowers. After a while it became a de facto license, with women like the notorious Susie Parker of Laramie, hauled off to court or jail if they failed to pay their monthly “fine” for belonging to the demimonde.

Bowers identifies four distinct types—even among the demimonde there was a pecking order. One group, called crib workers plied their trade independently of each other, though they tended to concentrate in one area of town, possibly to make finding them easier for their clients. If photos of Laramie’s exist, they are unknown, but police records, according to Bowers, document shacks in certain alleys near the railroad tracks where these women plied their trade.

Another group, slightly higher in the pecking order, were known as working in “cottages.” They had an actual house. Here they may have had a daytime occupation as laundress or seamstress.

Sporting houses

In Laramie, the top of the pecking order featured women who worked together in establishments, sometimes know as “sporting houses” but better described as brothels. A “madam” hired the girls and maintained order. Some were more elegant than others, with central or downstairs rooms where libations might be served and card playing indulged. Small rooms upstairs were assigned to individual girls.

The Second Story Bookstore in Laramie at 105 Ivinson Ave. is reminiscent of a place of this type. However, the eastern portion of the second floor was originally built as a dance hall, and the western portion might actually have been a legitimate hotel, at least for a time.

Laramie never really had the most prestigious type of bordello, the “parlor” house, according to Bowers. There was one in Cheyenne, called the “House of Mirrors.” Several of the girls who worked there wound up in Laramie, such as Christy Finlayson, a Scottish-born 30-something woman who was very successful, known around Laramie as “The Blonde” or “Puss Newport.”

John Grover

Madam Della Briggs also operated a Laramie bordello. John Grover owned Della’s bordello at 707 South 4th St. For a year or so in 1885, Della actually had a liquor license issued by the city of Laramie. The house, which is still standing, sports a rear second story entrance off the alley, possibly for whose clients who wanted to be discrete.

John Grover was the kingpin of the demimonde circuit in Laramie. He came to town from Maine as a grocer with a wife and child but soon they dropped out of sight. His sporting house, called the “Grover Institute,” was founded in the 1870s, though the property on the south side of Grand Ave, between 2nd and 3rd Streets was owned by Christy Finlayson. John Grover married Christy Finlayson in 1882. But the new Mrs. Grover had a short wedded life. Six months after the wedding she died of a gunshot wound to the temple, ruled as suicide by the coroner.

The value of Christy Grover’s estate upon probate is astounding. With total value of $6,245.25, it included two buildings and $3,617.53 in cash and personal property. Her diamonds, fancy piano and elegant furs indicated the level of her success.

As soon as her estate was settled in 1883, Grover married one of the other girls in the establishment, Monte Arlington, a young protégé of Christy’s. He provided a handsome tombstone for Christy in Greenhill Cemetery.

Monte Grover occasionally appeared in the newspaper with the “usual infractions” Bowers reports. However, in 1895 it was charged that she stole some money from a misdirected letter. A federal infraction, the charges were handled by a district postal inspector in May of 1895 but were dismissed by U.S. Commissioner J.H. Symons after a hearing in Laramie as reported in the Boomerang.

However, just a month later, on June 27, 1895, the Boomerang reported that Monte attempted suicide by drowning—she was rescued from the Laramie River and taken home by people who happened to be there. Her husband, interviewed in the newspaper, said she was “out of her mind” and greatly troubled by the recent charges against her. By December, she was dead. Carol Bowers discovered through a coroner’s inquest that John claimed Monte died of starvation, convinced someone was trying to poison her. The coroner’s jury accepted his explanation and ruled “starvation caused by insanity.” Apparently no one asked or investigated to see if John Grover (or anyone) had in fact poisoned her.

John Grover saw to it that his third wife was laid to rest under the tombstone of his second wife Christy, but he did not add Monte’s name to the marker. He relocated the “Institute” to 311 Front Street as shown in the Laramie City Directory of 1897. By 1900 he rented the Institute to Minnie Ford, according to Carol Bowers, and departed for California where he married a fourth time in 1904. In failing health, he committed suicide in Los Angeles in 1912.

UPRR helps out

Susie Parker, of 313 South First St. an “aged negress” as the Boomerang headline stated, died on August 28, 1922. At over age 70, she was one of the last of the pioneers of what the paper called the tenderloin district of Laramie. With her passing, the more overt days of the brothels ended in Laramie. The UPRR helped by deciding to rid Laramie of the red light district altogether.

The original depot at First St. and what is now Ivinson Ave. burned in 1917. The railroad began purchasing land between Garfield and Park Streets on the east side of the tracks along First St. Their goal was to obliterate the ramshackle bordellos there. They developed this land for the new depot and park in 1923.

However, it took more than that to shut down the operations – mostly they just stayed in the 200 and 300 blocks of First St., or moved further south. One had moved out into the county. But in 1956, Germaine St. John has learned, the city finally put the brothels out of business with raids on all of them. Thus ended an era in Laramie history.

July 20 tour

The walking tour to visit some of the sites where these businesses flourished will be at 5:30 on Friday July 20, leaving from the Wyoming Women’s History House at 317 S. 2nd Street. The tour is free and open to the public, though the subject matter may be inappropriate for youngsters.

Tour leader Germaine St. John began employment in Laramie’s downtown in 1946. At age 12 she worked after school, weekends and summers at F.W. Woolworth & Co. (now the Curiosity Shoppe) until graduation from Laramie High in 1952. Then she worked for Northern Gas Co., and after attending UW had a long career with First Interstate Bancorporation (now First Interstate Bank). She married Dale St. John, an elementary school administrator. She served on the Laramie City Council and was elected Mayor in the late 1970s. Now a widow, she has researched the red light district of Laramie, realizing that who and what she knew about the latter days of this mostly unpublished activity will be lost with her generation.

She will describe for participants several distinct eras in Laramie’s history when bordellos flourished. She’ll leave it to the audience to decide what standards should apply in judging the world’s oldest profession.

By Judy Knight

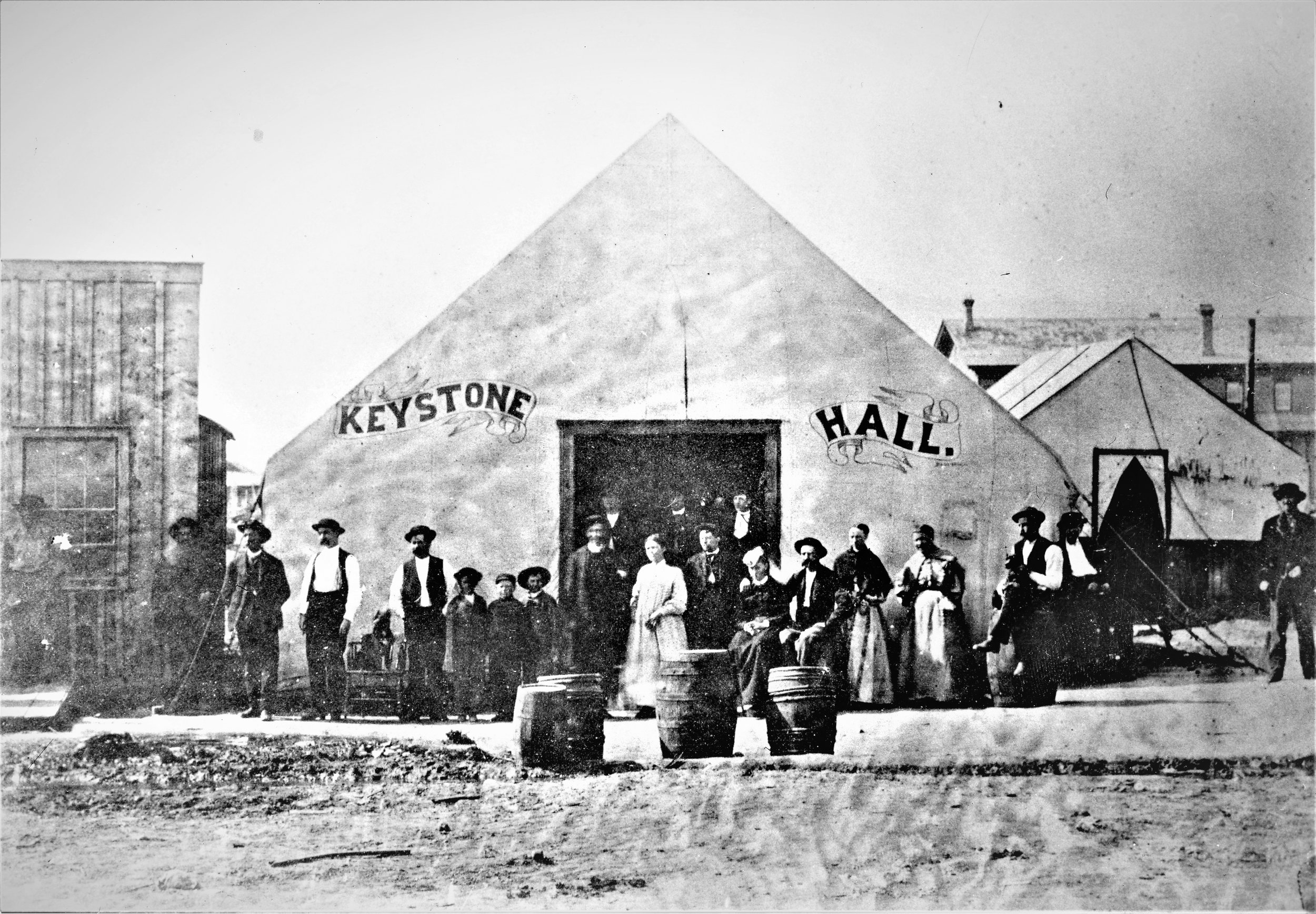

Caption: “Keystone Hall” was a bar, gambling casino, barber shop, restaurant and home for the proprietor and his family, according to Thomas Magee who arrived in Laramie in summer 1868. In his article “A Run Overland,” published in the December 1868 issue of the Overland Monthly and Out West Magazine, he commented about the proprietor’s wife: “She was surrounded by laborers, gamblers…general dirt and grease and…looked as if she had not a soul to sympathize with her in the world, and as if she had not a comfort in life. Women have a terrible life of it in these frontier towns, and I do not wonder that many of them become unsexed by their isolation among the roughest possible specimens of men.” Note the tent on the right in back, which may have been a temporary bordello. Behind it is the Laramie UPRR depot. Photo taken in 1868 by Arundel C. Hull, courtesy of the Laramie Plains Museum