Laramie’s Glass Factory—A Doomed Enterprise

An old landmark of Laramie has come to light with the opening of the new Snowy Range Bridge over the railroad tracks. It is a large stone building, a remnant of Laramie’s original glass factory. It sits behind the Gas Light Motel on 3rd Street, especially visible when traveling east over the tracks and looking to the left.

Since the town’s founding in 1868, Laramie residents were intent on making the Gem City of the Rockies, as it was called then, into a manufacturing center. The first big coup came in 1874 when the Union Pacific Railroad built a rolling mill to melt and recast worn rails.

By 1881, the Laramie Sentinel newspaper was touting the presence west of Laramie of large deposits of “soda” which could be refined into sodium carbonate for making glass. The editor believed this could lead to the construction of a glass factory. Albany County also possessed the other two main components to make window and bottle glass, silica found in sand, and calcium oxide found in limestone.

Nothing was done at the time but the effort received a new push in 1884 when the Laramie Boomerang raised the issue anew, but again no action was taken.

Glass company founded

The newspaper talk must have planted a seed in the minds of two Laramie men, attorney and business booster Stephen W. Downey, and businessman John Donnellan. In early March 1887, they traveled to Ottawa, Illinois, to examine the requisites necessary for manufacturing glass. Upon their return, Donnellan was positively effusive in his belief that Laramie was the ideal location for glass manufacturing.

He noted that all the raw material was readily available nearby except for coal with which to fire the furnaces. He remarked, however, that it could be obtained inexpensively via the Union Pacific Railroad. At the same time Downey addressed a letter to the Boomerang urging the citizens of Laramie to overcome their differences and commence construction of a glass factory immediately.

His plea bore fruit within a month. In April 1887, Downey and Donnellan were joined by other Laramie businessmen, forming the Laramie Glass Works. Grocer A. S. Peabody was elected president of the consortium. A manager, H.L. Rochelle, was chosen and sent east to acquire the equipment needed to commence operations. He was also tasked with hiring men to run the machinery. He noted that it would take about 50 men and the city should prepare for the “boom” to come.

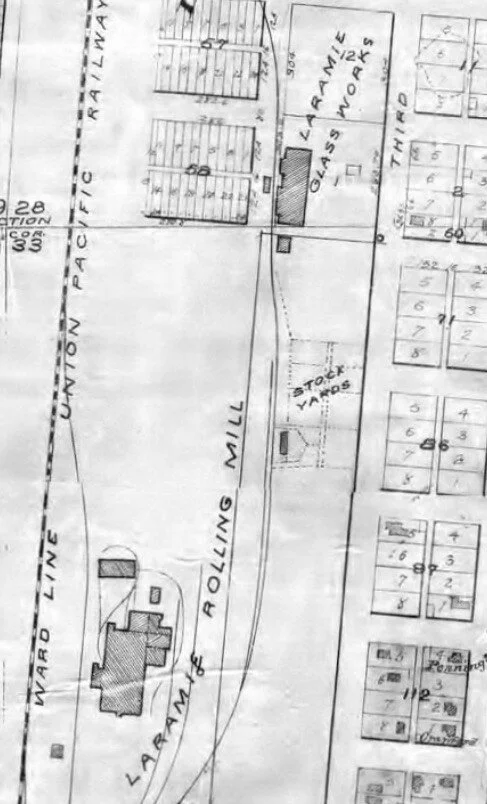

Land was acquired from the railroad on the north side of town near the old stockyards and bids were put out for construction of the building on May 11th, based on the plans of Laramie architect G. A. d’Hemecourt. Work started immediately and within 60 days the structure was completed, and the machinery installed.

Clean and pure

The trial run of production was done in mid-July with the results deemed to be excellent with the glass “clear and pure.” The workers, many immigrants from Belgium, were brought in from Illinois, likely the Ottawa glass works.

Regular production at the factory was achieved in late August. The Boomerang noted on September 22, 1887, that it had interviewed the factory manager and he said the window glass production would be at maximum operation in less than 30 days and then the factory would start production of bottles. One of the officers of company stated that there would soon be a "nest" of glass factories in Laramie.

Enthusiasm for the glass factory continued to run high in early 1888. The Boomerang reported that the factory’s success would cause the city population to swell to over 50,000 soon. Reality, however, soon replaced that wishful thinking.

Manufacturing halted

The source of the soda needed to produce the glass was the so-called “Soda Lakes” located about 13 southwest of Laramie. We now know these as the Laramie Plains Lakes a locally popular fishing spot. At the time, the Soda Lakes would dry up every summer and the soda could be mined and sent to town to be refined in the Union Pacific’s “chemical plant.” There it would be treated to extract the sodium carbonate need by the glass factory.

However, that year the Pioneer Canal seepage caused the lakes to retain water all summer. Soda could not be mined and the sodium carbonate not available to the glass factory.

New company takes over

This may have been the immediate cause of the factory ceasing operations. That in turn caused the original consortium to lose interest in the project and they leased the factory to a new group headed by Laramie banker Henry Balch retaining the name Laramie Glass Works. The transaction was completed on 18 July.

The company announced that they would restart operations on September 4th. That plan was nearly disrupted by a nationwide glass workers strike. The union insisted that operations could not resume until early October. Local workers, much to the benefit of the Laramie Glass Works, defied the union by a unanimous vote on August 22nd. Operations commenced as planned.

Despite the Boomerang stating that the factory was “besieged with orders,” soon reality struck again. Balch reported in December that the company had not made any profit since reopening. The price of glass had fallen 30 percent, mainly due to cheap imports flooding in from Europe.

There were also other issues at hand. A reporter from the Cheyenne paper looked over the operation and noted that the machinery was not suitable for larger scale operations. This was compounded by the cost of transportation of the glass to market. Competitors in Pennsylvania and Illinois talked the railroad into discounted shipping rates that were not offered to the Laramie company.

The company terminated operations completely at the end of 1888 and by March 1889, a foreclosure notice was printed in the paper with outstanding debt listed at $159,000.

Foreclosure

Others in town still saw potential in glass manufacturing. The raw materials were close at hand (the flooding problem at the Soda Lakes had been overcome) and a group raised $4,000 by August to restart operations under the name Laramie Cooperative Glass Company.

The problems detailed by the Cheyenne reporter caused an equipment failure to shut down operations in October 1889. The Belgian workers conducted cleanup operations. Almost immediately the local investors started looking for a scapegoat and pinned the failure on the workers.

Animosity soon boiled over and locals assaulted some workers. A solution to the conflict was found when the workers were eventually given free passage on the railroad back to Illinois.

Over the next 25 years there were repeated rumors that the factory would reopen and even that additional glass works would be constructed. That never happened despite efforts by locals, principally Stephen Downey.

Eventually the building was converted for the Acme Company to produce plaster. Later it was a sponge iron demonstration plant operated by the U.S. Bureau of Mines, and after that it became a warehouse.

By Kim Viner

Editors Note: At the time this article was first published the official name of the new viaduct over the Union Pacific Tracks had not been decided.

Caption: This photo taken from the top of Old Main on 9th Street looking northwest shows the original glass factory complex with its twin smokestacks off 3rd St. off in the distance on the top right. On the left side of the photo sits the Union Pacific Rolling Mills, where the Safeway shopping center is today. Exact date unknown, but would be around 1887 when Old Main was built. Photo courtesy of the Laramie Plains Museum.

Caption: Laramie City map from the time the glass factory was in operation, showing its location on 3rd St. and north of the first location of the Laramie stockyards about where the Snowy Range Bridge is now. Courtesy of Kim Viner.