Martha Salisbury Boswell: a typical pioneer’s story inferred through that of her husband

Like most of the women who wound up in the new town of Laramie, Martha Salisbury Boswell didn’t do anything spectacular, she stayed in the background. But what she endured may be typical of many a young wife on the frontier.

Left with her parents

Martha Salisbury Boswell (1836-1893) was living with her parents in Elkhorn, Wisconsin at the time the census-taker found the family in 1860. She had already been married for two or three years, but her husband, Nathanial Kimball Boswell (1836-1921) had “gone west.”

Martha’s parents were Russel (sic) and Mary Salisbury, except the surname was spelled “Sailesbury” in the census. There were three siblings listed: Sarah, age 19; Barton, age 11; and Rebecca, age 7, along with Martha who was oldest, at 23. Their father was listed as a carpenter.

9-year separation

“N.K.” “Uncle Kim,” or “Boz” as her spouse was usually called, had been born in East Haverhill, New Hampshire. He was somewhere in the middle of the 12 children born to Lucinda and John Boswell, both of Scottish heritage.

At the age of 19, his father gave Nathaniel “majority” status and probably conferred his blessing for the son to go off and make something of his life. What he did was go west to Wisconsin, where his life as a timber cutter was almost the death of him.

As the story goes, N.K. and two other men set off in a boat headed for an island in Lake Michigan to cut wood. The boat capsized, one man drowned, and though the remaining two were rescued; Boswell contracted pneumonia. We know that Martha and Nathaniel were acquainted before the boating accident, and that Boswell was one of a horde of young men working in Wisconsin forests at the time.

Family lore also indicates that Martha and Nathaniel were married in her hometown of Elkhorn. Accounts vary on whether the marriage was in 1857 or in 1858. Regardless, shortly after the marriage Boswell left and the two never lived together again for at least 9 years. “Lung fever” as pneumonia was called at the time was a serious health complication, and Boswell got advice that it would be good to venture further west to regain his health.

What did Martha do?

We are left with almost no information about what Martha did for 10 years except stay close to her parents and siblings, but there is plenty of information about what her young husband did. He was busy prospecting for gold in Colorado and practicing the use of a gun. He did not sign up for the regular Army during the Civil War, but he did join a regiment of Colorado Volunteers in 1861.

One bit of action he participated in was just before the war ended, in June of 1864, when the Colorado Volunteers executed what is called now the “Sand Creek Massacre.” Over 100 unsuspecting Native American leaders, their women and children were annihilated in a vengeful military attack in southeastern Colorado. Boswell is reported to have been an early casualty of that operation, which might have meant friendly fire as the Indians lacked firearms.

Surely they exchanged letters so Boswell could tell Martha of his adventures and that in 1867, tired of soldiering and prospecting, he traded his mining claim for the contents of a drug store with a druggist who had gotten “gold fever.” With no background at all in the drug business, he saw an opportunity to be the first druggist in the new town of Cheyenne. He set up shop with a partner named Taylor, and also along for the adventure was Nick Spicer, another former Colorado miner.

Rowdies who arrived in a new town on the railroad included an element that had to be encouraged to leave town immediately. Spicer and Boswell may have been the ringleaders of a vigilante mob that successfully rid Cheyenne of undesirables. While this was going on, the railroad tracks reached Laramie. Boswell and Spicer decided to bring law and order to another new town.

In Laramie, Boswell built a more substantial drug store than the one in Cheyenne. He sent for Martha and she arrived at least by 1870, though it might have been much earlier. Finally reunited, they set up housekeeping.

Nurse and jail cook?

Wounded people were initially taken to the drug store for treatment, as there was no other medical facility in the beginning months of Laramie. Was Martha there, and was she forced into becoming a nurse? We will never know for sure. Boswell said many years later that the injured taken to his store were usually the victims of the outlaw saloonkeepers and gamblers who came along with the railroad; violence was their stock in trade.

Boswell and Spicer organized a “vigilance committee” in Laramie, and after a few hangings, the vigilantes had the town more or less cleaned up. Boswell’s leadership ability and reputation caused Territorial Governor John Campbell to appoint N.K. Boswell as the Sheriff of Albany County on June 7, 1869. (The first man appointed Sheriff of Albany County, J.W. Conner, apparently never came to the county, so Boswell was the first to actually serve, though the second man appointed to the position.)

For the next ten or so years, Boswell was usually elected Sheriff; he and Martha lived in an apartment which was in the basement of the new Albany County Courthouse, which also held the jail. Martha probably did her part as the cook for the inmates as well as for her family. During this time, the Boswell’s only child, Minnie (1876-1932) was born.

Also residing in the Sheriff’s quarters in the Courthouse was Martha Boswell’s sister Rebecca and her family. She was married to Richard Butler who became his brother-in-law’s deputy. Their granddaughter, Lois Butler Payson, a professional librarian, together with a Salisbury cousin, Charles Pope, provided family details.

Those memoires and photos of the man his niece and nephew called “Uncle Kim” are now at the UW American Heritage Center and the Laramie Plains Museum. They are mostly the result of research collected by Laramie author Mary Lou Pence, for a historical fiction book based on the life of N.K. Boswell published in 1978.

A home of their own

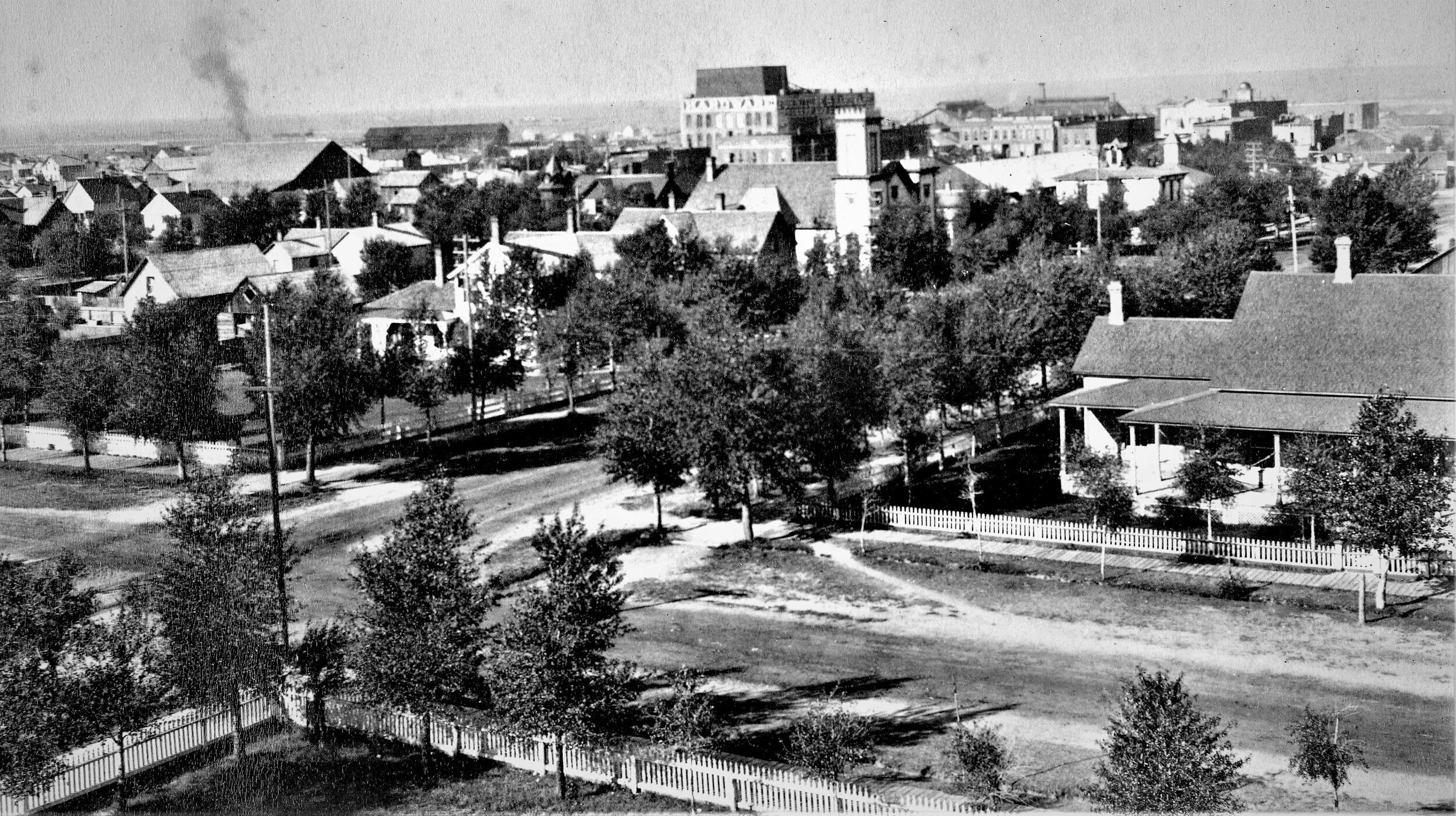

In 1882 the Boswells arranged to have an officer’s building from Ft. Sanders moved into Laramie and placed on a lot at the corner of 5th and Grand Ave. Now Martha had a regular dwelling to be “keeping house” in. The military fort three miles south of Laramie was being decommissioned and many buildings like the Boswell’s were moved to town.

By the early 1880s Boswell was fed up with being Sheriff. He didn’t like being forced by the county commissioners to be their agent to collect back taxes from residents who were delinquent in their payments. In the early days of his tenure, that could have meant a horseback ride all the way to the Montana border, as the northern limits of Albany County extended that far until 1875.

Sheriff Boswell devised a unique but probably unpopular solution by publishing in the newspaper the names of delinquent taxpayers and the amount owed. It appears that he hoped to shame them into paying up rather than being forced to ride to the four corners of the county collecting taxes in person. He didn’t run for sheriff again and in 1881 became the chief of the detective bureau of a stock growers association, with headquarters in Denver.

Newspaper accounts between 1882 and 1884 have frequent reports that “Inspector (or Stock Detective) Boswell of Cheyenne” was visiting Laramie. All of Wyoming was his territory for apprehending cattle rustlers, so a headquarters in the Territorial capitol may have been necessary, but at the same time, there are accounts of Martha entertaining ladies of the Methodist Church at her home in Laramie, so apparently they maintained two residences.

Ranch wife

About that time, Boswell started buying land in the area around what is now Wyoming State Highway 10 on the border between Colorado and Wyoming. Sometime after 1882, he acquired a half-interest in a ranch in the area on the Big Laramie River. A ranch house was already there which Boswell may have enlarged, and he and his son-in-law Charles Oviatt built the large log barn that still stands on the property.

Summers were spent on the ranch, which was a favorite destination for Laramie picnickers starting around 1885. One anecdote is that Martha Boswell was famed for her pies that were produced in abundance for summer visitors. If newspaper accounts of the visitors to the ranch report only a fraction of those who came to see “Old Boz,” there truly were hordes for Martha to feed. One could hope that at this stage in her life she had plenty of help in the kitchen.

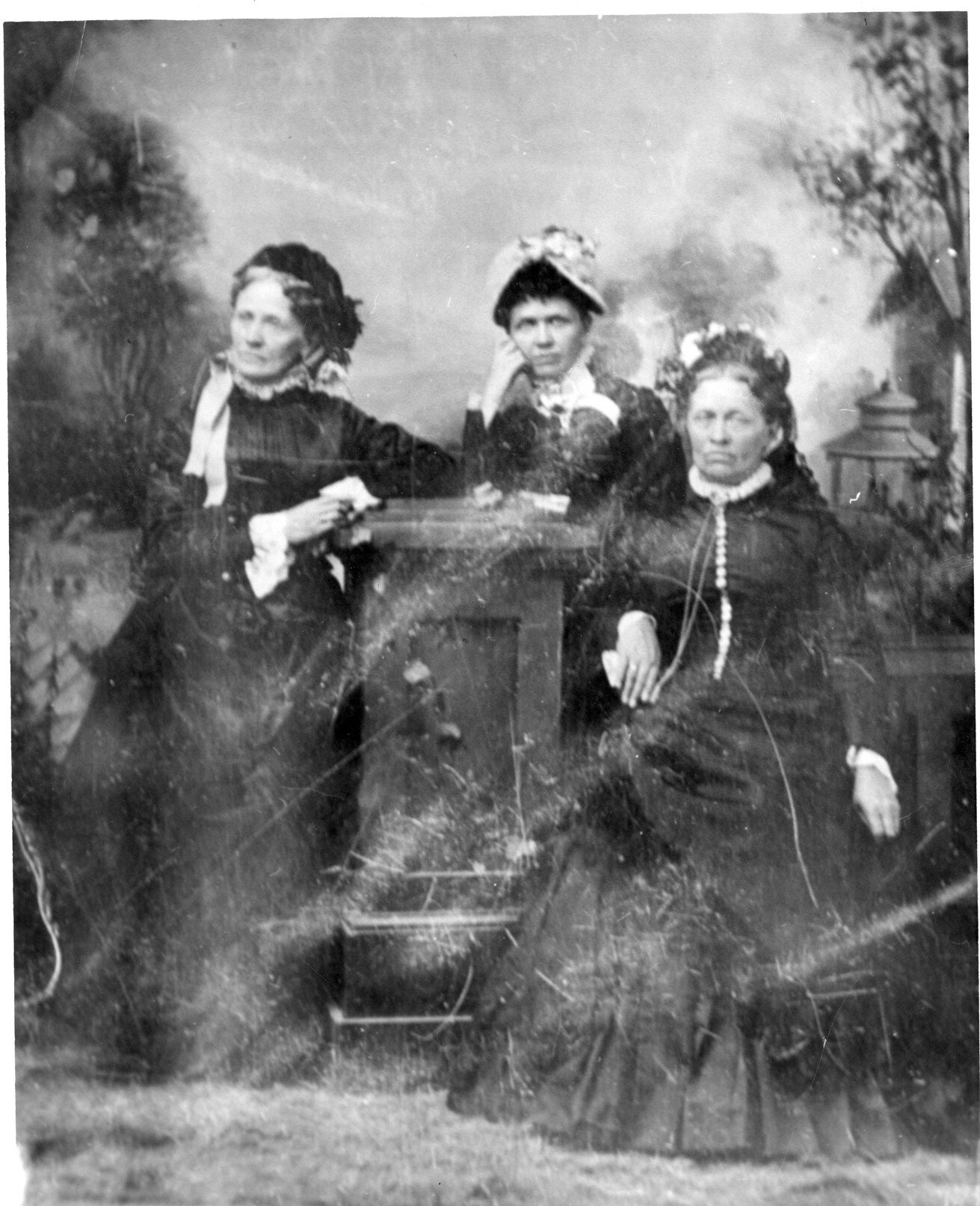

Throughout her life, Martha appears to have had support from her two sisters and their families. The only extant photo of her is a damaged print taken in Laramie of an aged-looking Martha with her two younger married sisters who, together with their husbands, answered the call to come to Laramie and help out at the jail and then at the ranch.

The three Salisbury sisters all put down roots in the Laramie area. In 1884 and again in 1885, the Boomerang reported that Mary Salisbury had been in Laramie to visit her three daughters, Mrs. Pope, Mrs. Butler and Mrs. Boswell, but was returning to her home in Stewart, Tennessee.

A quiet death

Martha did not live to see the marriage of her only child, Minnie, so she never knew her two grandchildren, Clarence and Martha Oviatt. She died on April 29, 1893 at her home at 208 S. 5th St., and was buried in Laramie’s Greenhill Cemetery. Her obituary reports that she had been on the rolls of Laramie Methodists since 1869.

The obituary notes that both of her sisters had predeceased her. If so, some of her “helpers” were absent at the ranch. It also states that she had been in poor health for 15 years. That would be the entire time she was baking pies at the ranch. Or did she mostly stay in town?

Of the many notices in the paper that “N.K. Boswell has left for his ranch,” there are none that add: “Mrs. Boswell accompanied him.” It appears that she stayed home in Laramie most of the time. After her death at age 56, N.K. Boswell continued for nearly 30 years his activities of ranch host, Republican politician, supervisor of work on building the State Penitentiary in Rawlins, and public speaking.

Boswell was acclaimed as “oldest resident of Laramie” when he died at age 85. “Bravest of Pioneers” was how he was lauded in the front-page obituary. “An Old Resident and a Good Lady gone from our midst” was Martha’s tiny headline, on page 4 of the paper many years earlier, when she was 56.

Typical of what obituary readers want to hear were the lines: “She was conscious, resigned and cheerful to the very last and suffered but little if any pain.” She may have been resigned and cheerful but the fact that she was “old” at age 56 indicates there is another story there that remains untold.

By Judy Knight

Photo source: Mary Lou Pence Collection, UW American Heritage Center

Caption: Left to right: Sarah Salisbury (Mrs. A. P.) Pope, Rebecca Salisbury (Mrs. Richard) Butler and Martha Salisbury Boswell in a damaged and undated Laramie studio pose.

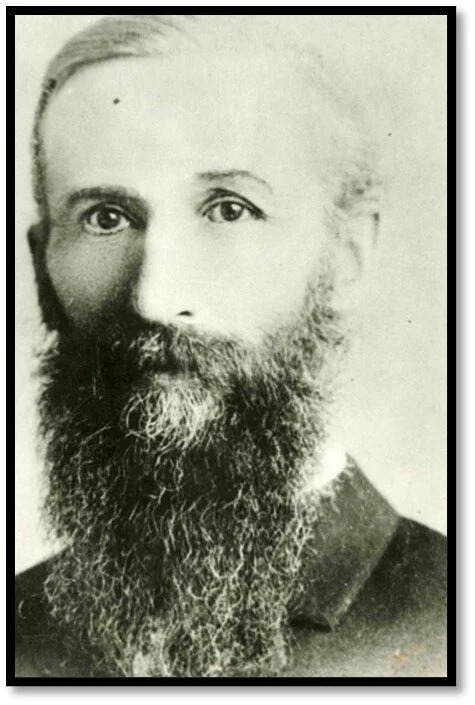

Photo Source: Pope Collection, Laramie Plains Museum

An early undated photo of N.K. Boswell shows him trying to look older with the bushy beard and mustache that he retained throughout his life.

Caption: A portion of the Boswell home is in the right foreground, at 208 S. 5th St. at the corner with Grand Ave. in Laramie. The photo was taken around 1890—it had been moved to town from Ft. Sanders around 1882. Now city-owned, it is in LaBonte Park and leased to Feeding Laramie Valley, a non-profit. The lot where the house was became a Conoco gas station for many years, and is now a city parking lot behind the City-County Detention Center that faces Ivinson Ave.