Diversity on the High Plains

It is generally regarded by many that the population of the high plains were much more culturally diverse than seen in early reports and popular culture. One of the most culturally diverse groups belonged to the cowboy profession. Part of this may be due to the social stratum of the cowboy which was quite low compared to most. The pay was low (on average $1 per day), the work was long, and not everyone wanted to do it. However, this left space for those who were willing to bare the wilderness, cold and danger.

Because cowboys ranked low in the social stratum of western society it is difficult to know exactly who was a cowboy. New research using US Census records suggests that approximately 25% of cowboys were black, 15% were Latino 20% were Indigenous. These are all guestimates and probably vary by region but gives a vastly different picture than that in pop culture.

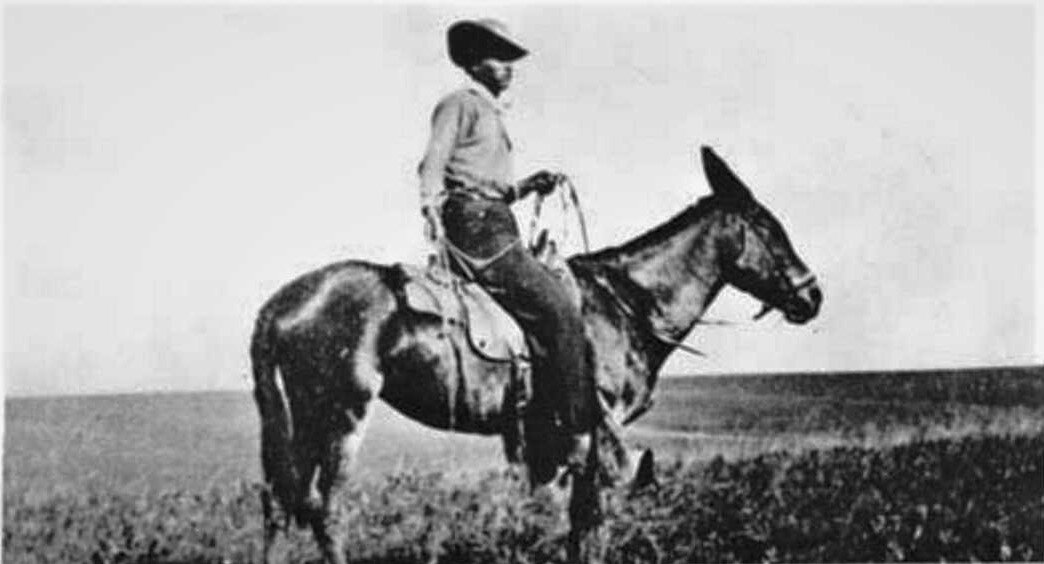

One such character was “Broncho” Sam Stewart. He was born in Mexico in 1852; Sam was part black and part Latino and fully dedicated to living his life to the fullest. His skill for wild horse breaking, bull busting and acts of feat were legendary in not just Laramie but according to early written records “from Mexico to Canada,” during his lifetime. A post about his life on Ancestry.com, states that he “grew up with the Caballeros [translates to “horseman of the southwest.”] of Mexico and Texas,” at the time of the Civil War.

Sam travelled north from Texas, ranging cattle with Charlie Goodnight to Cheyenne, Wyoming (the railroad was built to this point in 1867). Around 1877 he worked as the postman between Fort Laramie and Laramie City. He displayed his prowess for breaking wild horses, staying astride a bucking horse or bull on every occasion it warranted, usually a holiday or rodeo or just for fun.

In “Wyoming Pioneer Ranches,” by Burns, Gillespie and Richardson, Sam went to work for Tom Alsop, Albany County rancher, breaking horses and working on the round-up. Tom ran a stage stop near the Big Laramie River. In the spring, it was common for the snow melt to flood the river. One year, Tom’s 3-year-old son, John fell in the raging water. Sam immediately “came a-running and jumped off the bridge fully clothed to rescue little John.” The family never forgot Sam’s deed and regarded him highly.

In 1881, Sam married Kitty who was identified only as “a full-blooded squaw.” Rumors convinced Sam of his wife’s infidelity. In 1882, he ended up shooting his wife and then ended his own life. Court documents seen by Gladys Beery (author of many local titles including “Sinners & Saints: Tales of Old City Laramie) regarding the incident show that the rumors were unfounded.

Another black cowboy who was famous during his lifetime in Laramie is Thornton Biggs or Thorn’t, as he was often called. Thornton was born into slavery in Maryland in 1855. According to Burns, he was known for training racehorses. After the Civil War, in 1885, Thornton married Molly Workman and had a son named Fred. It is unclear why or what happened with his family, but Thornton made his way west and there is no indication that there was any contact between the them after this point.

According to Holly Hunt, Albany County rancher, he came west with Owen Hogue as a cook with the trail herd. Ora Haley, another well-known Albany County rancher, purchased part of the cattle from Owen and Thornton stayed with the herd. Thornton worked for Ora Haley and was regarded highly by the cowboys. In “The Negro Cowboys,” by Durham and Jones, Ora credited part of his success to the knowledge and hard work of Thornton. He trained “a whole generation of future range managers, wagon bosses, and all-around cowpunchers the finer points of the range cattle business,” though he was never promoted to any of these positions himself.

Thornton was said to posses an “animal sense,” which allowed him to pair a lost calf with its mother among thousands of other cattle. Legend said he had a knack in healing the sick and injured.

Thornton is mentioned in relation to a scandal around 1900 in a downtown Laramie establishment where the barman was shot. The story was made sensational by the newspapers and Thornton’s name was in almost every edition regarding the scandal even though he was not implicated in the murder.

Despite this Thornton was frequently cited in the newspapers also for his participation in local rodeos and events. He often raced horses.

Around 1920, Thornton went to work with Holly Hunt. According to Holly he “stayed with him as long as he was physically able. He was an outstanding cowman as well as being a very loyal and devoted to the Hunt family.”

It is unclear how long Thornton stayed with Holly, but the 1940 US Census shows that Thornton lived the last of his days at the Colorado State Hospital until 1940 when he died. Thornton lived to be about 90 years old.

Both Sam and Thornton are examples of Diversity on the High Plains. It is fortunate that information exists on these two characters, due in part to their fame during their lifetimes. With further research, hopefully a more detailed picture will emerge.

By Konnie Cronk

Bronco Sam on his mule. Laramie Plains Museum Collection