Charismatic lawman N.K. Boswell; He brought law and order to Laramie

New Hampshire native Nathaniel Kimball Boswell (1836-1921) was in the right place at the right time to make a name for himself in the raw frontier of Wyoming Territory in 1867.

A true hero

He was a man who “stood for law and order, right and justice and by his bravery did much toward developing the high standards of citizenship,” said the Laramie Republican at the time of his death in 1921 at nearly age 85.

Boswell is also remembered in Laramie as an investor in soda mining, contractor, rancher, and prison warden. But it is as a lawman on which his notoriety rests.

He was somewhere in the middle of 12 children whose parents were descended from Scottish settlers of New England. When he was about 19, he sought his fortune out west as a timber-cutter in Wisconsin.

Nearly drowns

That ended badly with a near drowning in Green Bay of Lake Superior. Before the accident, he had married Martha Salisbury (1836-1893) of Elkhorn, Wisconsin in 1857. He recuperated, probably at her parents’ home. But “lung damage” was diagnosed and he was advised to seek dry air, though predictions were that he wouldn’t survive the journey.

But he did survive the ride with a wagon train to Colorado around 1858. Martha stayed with her parents in Elkhorn, and was still there at the time of the 1860 census. As the oldest child, she was part of a close family; two of her sisters and their families joined her in Laramie when the Boswells became established in Wyoming Territory.

That took nearly 10 years before Boswell or “Boz” as he began to be known, settled down. Though he would go back to Wisconsin from time to time and reportedly became a Mason there in 1863, mostly he was in Colorado, staking claims along Cherry Creek.

He told a grandson that he was involved in a Denver lumbering business with the Holliday brothers who, after Boswell sold out to them, came to Sherman (between Laramie and Cheyenne) and then to Laramie. So between approximately 1858 and 1867, Boswell was in Colorado, where he also volunteered with a Colorado military company that was organized during the Civil War.

But in 1867 he traded mining claims for the contents of a drugstore. He headed to Wyoming Territory as the Union Pacific Railroad (UPRR) was reaching Cheyenne. A friend from Colorado, Nickolas Spicer, who later became Laramie mayor, came with him.

An unlikely druggist

Boz” began his days in Cheyenne as a druggist without any knowledge of the business. He opened a store on Eddy St. and might have hired an actual druggist. The store was known as “Boswell and Taylor” though Taylor is mentioned only briefly.

There were some unsavory people among the other Cheyenne settlers. Boswell and his friend Spicer set out to rid the town of some of the worst. They participated in or instigated a vigilante group that used a novel technique. They roped several together with signs saying they were crooks, and gave them the opportunity to leave town. That suggestion was quickly obeyed.

So Boswell demonstrated the ability to gather others around to help carry out plans. His charisma may be a large part of what allowed this lawman to survive to well past the age of 80.

By the time the dust settled in Cheyenne there were three other drug stores to compete with Boswell & Taylor, so Boswell along with Spicer decided to move on to the next major settlement along the tracks—Laramie

Laramie merchant

Boswell opened a drugstore in Laramie on Second St. in 1868. He acquired a log house between Grand and Garfield Streets on Second, and sent for Martha. He also contracted with the UPRR and with Fort Sanders to supply vegetables. Often he was out of town securing supplies.

The early days of Laramie were much like they had been in Cheyenne. Residents who had been shot by the rowdy element were taken to Boswell’s drugstore for treatment as lawlessness prevailed. The Laramie Boomerang of Feb. 22, 1913 uses material from a lengthy interview with Boswell, then age 76, in which he recalls how a vigilance committee in Laramie was formed.

Boswell steps forward

As Boswell tells it, the worst of the Laramie desperados was Sanford O.S. Duggan, who declared himself city marshal. Duggan and his cronies had seized control of what passed for government in Laramie in summer 1868 while Boswell was setting up shop.

Once when Boswell was away the “marshal” went around to businesses seeking funds for treatment of a boy who had been shot by Duggan’s own police. When he returned, Boswell learned that Duggan had gotten $80 from patrons and staff at the drug store. But Duggan kept the money; Boswell found the boy in desperate straits. An angry mob confronted Duggan, and Boswell stepped forward, demanding that Duggan produce the money collected for the wounded boy.

Boswell gave Duggan 15 minutes to produce the funds, and persuaded the crowd of “700 or 800 men” to hold off on their demand to lynch Duggan. The tactic worked; Duggan produced the funds immediately from the gambling tent. He gave the money to Boswell, who gave it to Dr. Finfrock to treat the injured fellow. Duggan left Laramie.

We can’t verify what Boswell told the reporter so many years later. However, word did get around that Boswell was a force to be reckoned with, a man who showed courage under pressure.

Appointed Sheriff

The reputation that began to cling to Boswell probably led the first Governor of Wyoming Territory, John Campbell, to appoint Boswell in 1869 as the Sheriff of Albany County. He wasn’t the governor’s first choice, but that man never came to the county. Thus the timber-cutter, merchant and vegetable contractor became a lawman.

As the first to actually serve as Albany County Sheriff, Boswell was in office for several terms though he held other positions at times, like first warden of the Territorial Prison, which opened in January, 1873. Boswell also became a deputy U.S. Marshal when he happened to be visiting Cheyenne when a miscreant needed to be apprehended.

Recruits women

As Sheriff in 1870, Boswell had special duties in a momentous event, the impaneling of newly-enfranchised women as part of juries. It was Boswell’s job in March, 1870 to make women jurors comfortable by sprucing up the makeshift courthouse. Not only did Boswell summon the women who were called to serve, he also appointed the local milliner Martha Symons-Boise, as the first woman to serve as a bailiff.

However, one job he particularly disliked was the demand of the County Commissioners that he collect property taxes from residents who had not yet paid. Since the borders of Albany County went all the way to Montana then, this would have required much time on horseback.

“Boswell is around collecting taxes” ran a short note in the Laramie Sentinel of September 6, 1872. Then he published all the names of residents who had not paid their taxes. This was not popular; Boswell, a Republican, did not even have the support of his own party in 1874 when the Republicans nominated W.S. Phillips for Sheriff.

Boswell found other work as the lessee (warden) of the new Territorial Prison in Laramie. But by 1879 he was back in office as sheriff again, and living in the basement of the new courthouse with wife Martha and their only child, daughter Minnie, age four.

His fame spreads

Boswell was not trigger-happy; his goal was to apprehend miscreants and keep them alive until they could appear before a judge or jury. He even did that with Duggan, the man he had faced down in 1868—apprehending him when Duggan returned to Laramie and escorting him back to Denver to face murder charges.

His days as sheriff ended in 1883 when he was hired as the chief detective of the Wyoming Stock Growers Association, in charge of apprehending Wyoming cattle rustlers, a job he relished and kept until 1887.

Murray L. Carroll, UW history professor, writes in Annals of Wyoming (Fall, 1987, page 18) that Boswell was the most well-known lawman of Wyoming in 1885. At that time, Governor of Wyoming Territory Francis E. Warren called upon Boswell to go with him to Rock Springs to investigate the Chinese Massacre that occurred on September 2, 1885.

Boswell’s role in the actions that resulted is mostly unrecorded, but this event in 1885 signaled Boswell’s availability as someone to turn to when the going got rough for law and order.

Ranching beckons

Around 1880, Boswell began buying ranchland south of Laramie. He placed ads announcing hay for sale.

In 1882, when Fort Sanders was decommissioned, he purchased one of the officers’ residences and had it moved to town. It was located at the corner of 5th and Grand Avenue, and still stands, though it was moved long ago to LaBonte Park. So when Boswell became a stock detective, Martha didn’t have to cook for prisoners and had a spacious home.

Boswell consolidated some of his holdings into a ranch on the Colorado border, along the Big Laramie River. William Hill was a partner in this venture but soon Boswell took over. After he resigned as chief of the stock detectives in 1887, he became a full-time rancher.

Prison warden again

Apparently Martha was not well during this period. She was 56 when she died at the Laramie house in 1893. Her obituary stated that she had been in poor health for 15 years. Therefore it is unlikely that she spent much time, if any, at the ranch. However, there was a large extended family of kin to both Boswell and Martha who stayed there with their families. Daughter Minnie and many nieces and nephews learned to ride and enjoy the great outdoors with “Uncle Kim” at the ranch.

He was persuaded to come out of retirement in 1897 to become the lessee once more at what had become the State Penitentiary in Laramie. “They will be making brooms again at the prison,“ said the Cheyenne Daily Sun-Leader on April 12, 1897 as Boswell was taking charge.

Soon after that he was appointed to a supervisory role at the new state penitentiary being built in Rawlins. Boswell was quoted in the Boomerang late in December of 1902 as saying that the new prison was in bad condition with poor heating. But he supervised the transfer of nearly all the prisoners from Laramie to Rawlins, which apparently went off without a hitch.

Rides with Roosevelt

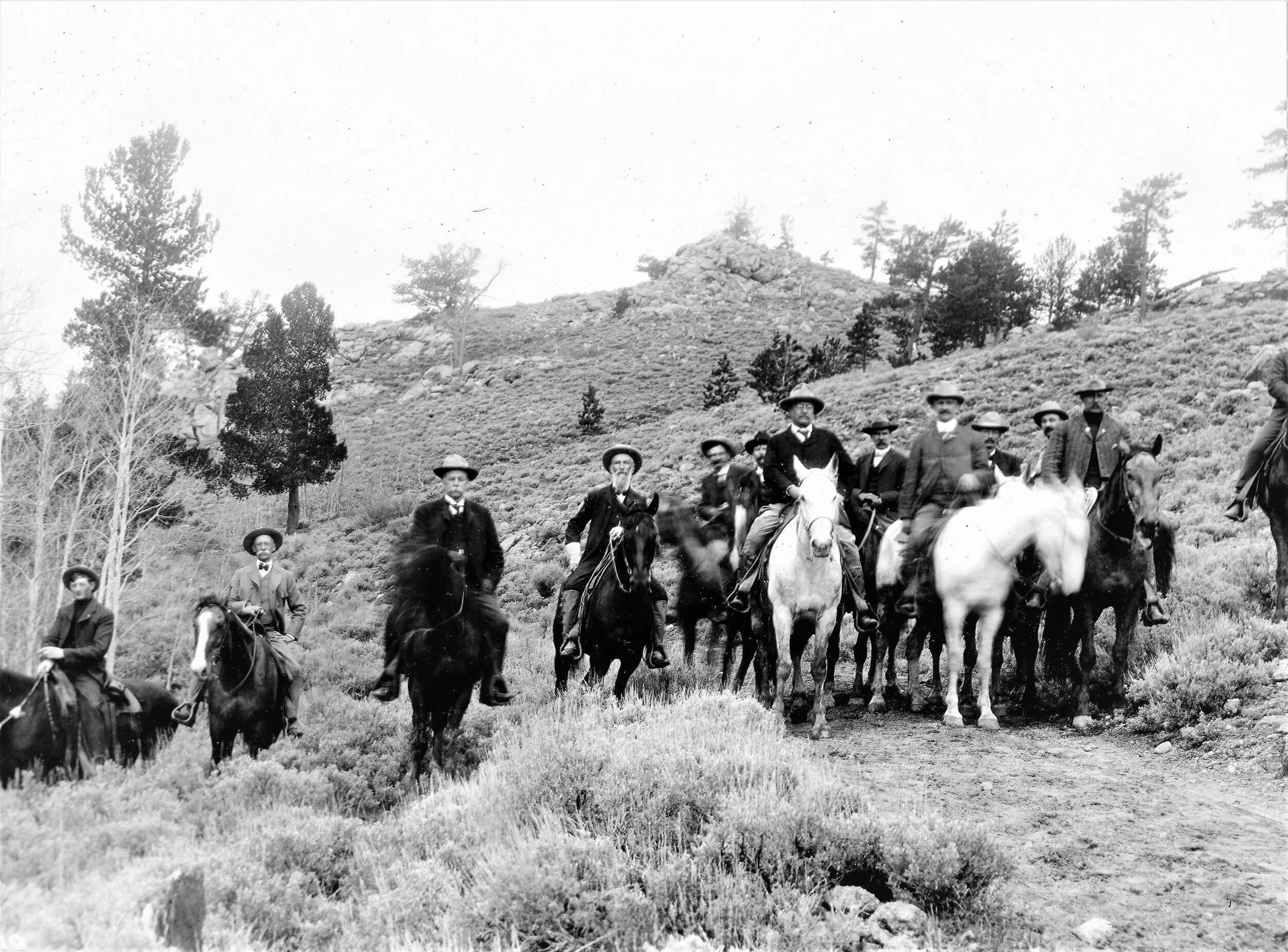

In 1903, Boswell was honored to be chosen as one of 10 riders to accompany President Theodore Roosevelt in a Memorial Day horseback ride from Laramie to Cheyenne. Pictures show that Boswell’s bushy beard was totally white, but he still sat tall in the saddle. He had a favorite mount named “George” according to a niece, Lois Butler Payson. He also said that he was the only rider in the party who went by horseback both ways.

In 1912, a news item in the Laramie Boomerang reported: “…N.K. Boswell has bought a fine new Franklin automobile that will run without horses when supplied with gasoline and his friends are laying awake nights planning for the numerous trips about town and to the country in store.” His friends were indeed angling for invitations to the popular ranch.

Mary Lou Pence of Laramie wrote a mostly accurate account of Boswell’s life, though embellished with dialogue that Boswell never spoke and accounts that make it part historical fiction and biography. Titled “Boswell; the Story of a Frontier Lawman,” it was published in 1978.

Boswell’s ranch was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1977. It is now protected with easements that restrict development.

When he died, Boswell’s entire estate went to his only heir, Minnie Boswell Oviatt (c. 1875-1932). Her spouse, Charles D. Oviatt continued to operate the ranch and served as a Wyoming Senator in the early 1900s.

Editor’s note: Mary Lou Pence’s collection at the UW American Heritage Center furnished material for this account. Other main sources are the Wyoming Newspaper Project (including hints of vigilanti activity in Nicholas Spicer’s 1907 obituary) available on line at https://newspapers.wyo.gov.

By Judy Knight

: Sheriff N.K. Boswell, undated. Laramie Plains Museum

N.K. Boswell, fourth from the left on the May 31, 1903 historic ride up Telephone Canyon to Cheyenne with President Theodore Roosevelt (on the white horse to Boswell’s left). The President’s physician, Dr. Rixey, is on the other white horse. Others in the party are from the left: W.W. Daley; Otto Gramm, F.E. Warren, Boswell, Seth Bullock from Deadwood SD, Joseph LaFors, Roosevelt, Frank Hadsell, Rixey, J.S. Atherly, W.L. Parks, and Fred Porter. Not pictured are John Ernest and R. S. Van Tassel who also made the ride. Laramie Plains Museum