Monster suffrage parade –May 3, 1914 Laramie student marches in Boston

Gladys Corthell (1890-1925) was not entirely thrilled to be bundled off to Boston in the fall of 1913 for her senior year of college. She was 23 years old. She had been attending UW, but her parents sent her off to Simmons Female College in Boston. The mission of the college, to educate women in fields “calculated to enable the scholars to acquire an independent livelihood,” likely appealed to her parents.

Her time in Boston meant separation for a while from her beau, Wilbur Hitchcock (1886-1930). The aspiring architect had graduated from UW in 1912 with a B.S. in Civil Engineering. He then taught classes at UW while designing houses in Laramie and preparing for graduate school.

A serious romance

Their romance was getting very serious. Her parents, attorney Nellis Corthell and his wife Eleanor Quackenbush Corthell, wanted her to get a broader view of life and experience being on her own before settling down.

Being away from Wilbur would give her a chance to focus on her studies. It wasn’t that her parents disapproved of Wilbur. He was a hard-working young man from South Dakota with a love of music, books and theater along with his passion for architecture.

Gladys and Wilbur had talked about the benefits of the trip. He gave her letters to read on the train, the first one not to be opened until the train reached Sidney, Nebraska. In this letter he encouraged her, saying “Now it seems best that you should have a year to develop your real self without any influence from me.” He concluded: “Be brave and happy.”

Still, it was a long separation for the young couple; they wrote letters back and forth almost every day. Most of those letters are still in the Corthell/Hitchcock/Mullens family archives.

Suffragists to march!

Gladys had been in Boston nearly a full academic year. She was living with her friend Helen in a rooming house near the campus when they learned about a major parade that was to take place on May 3 in support of women’s suffrage. Gladys had never marched for suffrage before because women in Wyoming had won the right to vote back in 1869 when Wyoming was still a Territory.

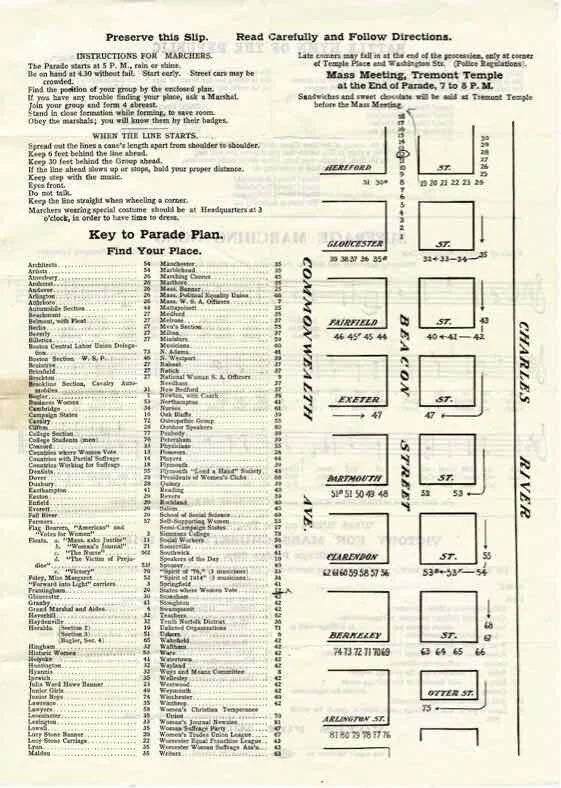

There were to be 81 units in the parade, with both male and female suffrage supporters representing everything from “Architects” to “Writers.” Delegations from other Massachusetts towns would be there, from Amesbury to Winthrop.

What’s more, there was to be a special unit given the prestigious number “12” near the front of the parade for “States where women vote.” It would have been exciting to witness the nearly 1.5 hour long parade, but even more so to be in it and proudly marching with the other westerners from states where women already had the vote.

Thousands of marchers

Her excitement and exuberance come through in the letter she wrote to Wilbur the next day, May 4:

“Well sir, I got up tireder and stiffer this AM than the morning after we climbed Snowy Range. And I’m glad they don’t have Suffrage Parades every Saturday. H[elen] and I sewed all day until 3:30 when we dressed and went down to join the Suffragists. Directions had been sent to us beforehand so we had no trouble locating our section.”

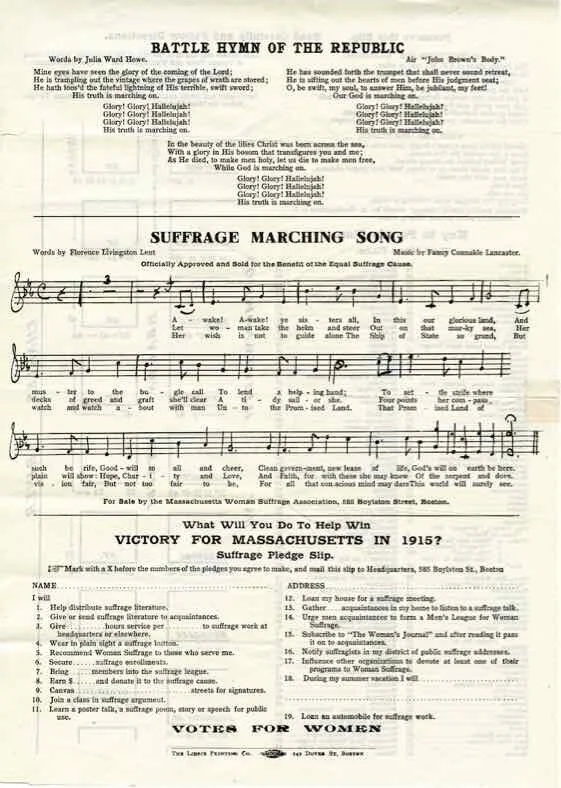

Those directions and the song for the marchers are among the mementoes of that amazing parade. Gladys brought them home to Laramie where they have also been preserved in the family archives.

Gladys continued: “We marched right behind the Wyo shield carried by a Sheridan girl who knows all the folks we know. Seven Thousand and more had pledged to march in the parade and from 12 to 15 thousand marched. Harvard had pledged 30 and 500 turned up. Men, women and children paraded. Yellow was the prevailing color among the thousands and thousands of spectators too. The anties sold over 100,000 of their red roses but even then they were scarce. We marched for an hour and a half – right past the Mayor and Governor too – who took off their hats to the States where women vote.”

A Library of Congress article titled “Suffrage Music on Parade” by Cait Miller dated March 13, 2019 noted that in the Boston parade “Women rode horses, women lawyers and doctors wore caps and gowns, ushers led the parade in red, white, and blue gowns as they carried ‘directoire canes’ in hand, suffragists executed five specially designed floats, and marchers proudly presented suffrage banners …”

“Such crowds of people!” said Gladys in writing to Wilbur. She went on to add: “Ropes were stretched along both sides of the street – and policemen were thicker than telegraph poles. The windows, fire-escapes, trees – every spot was occupied. Moving picture machines up on telegraph poles etc. It was worth the long march to hear the Scotch Bagpipes behind us and to see the people.”

She concluded: “I expected to be hit with eggs and lemons at least but didn’t even hear a slurring remark. H. and I didn’t stay to the mass meeting [large gathering at the end of the parade] – couldn’t stand the pressure (literally). We ‘held forth’ coming home on the car – to the amusement of a great many. Mass. women will soon be on the voting list. I’ll bring my ‘Equal Rights, Votes for Women’ pennant home to you as a souvenir. It was all a wonderful experience and I’m eager to see its effect.”

Results come slowly

The parade got a little notice in Wyoming. The May 26, 1914 issue of the Wyoming Semi-Weekly Tribune in Cheyenne noted:

“The women of Boston and Massachusetts who are fighting for universal suffrage held the first great suffrage parade ever seen in Massachusetts, when possibly 15,000 men and women marched through the streets, and from 300,000 to 500,000 men, women and children cheered them all along the line. This monster parade was reviewed at the state house by Governor Walsh and Mayor Curley, the former saying of it, ‘No citizen could witness this outpouring of earnest and high-minded women without appreciating the great importance of the movement. This day's events will serve to attract more thought and deeper consideration to the vital problems of equal suffrage.’”

Her prediction that women of Massachusetts would soon be able to vote did not happen as quickly as Gladys hoped. The Massachusetts Legislature became the 8th state to ratify the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution in 1919. But nationwide suffrage didn’t become legal until August 18, 1920, when Tennessee became the 36th state to ratify.

A sad postscript

Gladys returned to Laramie in late spring, her class credits were accepted at UW and she did graduate. She and Wilbur Hitchcock were married on June 30, 1914 at the Corthell farmhouse in West Laramie. By the time seven years had rolled by, they had four children: Eliot, David, Clinton, and Elinor. The happy procession of their life was interrupted way too soon when Gladys died in 1925 of complications from surgery. She was 35 years old.

My mother, Elinor, was four and the youngest of her children when Gladys died, so she had very little memory of her mother. But as Gladys’ granddaughter, I heard stories about her as I was growing up, and feel fortunate to have the letters and other tangible remembrances of her.

By Ann Mullens Boelter

Photos are all from the Hitchcock/Mullens/Boelter family archives

Gladys Corthell, ca. 1912

Caption: Marching Song and a Suffrage Pledge Slip to help win the vote for women in Massachusetts; a flier given to all 15,000 marchers in the Boston Parade, May 3, 1914.

Directions for Boston parade showing instructions for parade lineup. Gladys marched with group 12 for “States Where Women Vote.”