Where did all the real western cowgirls go? They ditched the skirts and became everyday legends

The term “cowgirls” has special meaning in Laramie, where it refers to the UW women’s athletic teams. Appropriately enough, the earliest cowgirls of renown were female athletes too, the trick riders and shooters of the Wild West shows.

The first use of the word “cowgirl,” however, referred to girls who did what was considered to be men’s work on western ranches. In 1885, the Cheyenne Democratic Leader newspaper referred to a “beautiful cowgirl” from Nebraska who was a wonder to behold doing work on the range. Of course she was beautiful, that was part of the myth.

That was the first reference I found for use of the word in a Wyoming newspaper. But the next year the Lusk Herald remarked about a certain Montana girl who actually sat “hair-pin fashion” on a cow pony to cut out cattle. Evidently it wouldn’t do to say she sat astride the horse like a man.

These girls could have been labeled as “tomboys.” However, Elizabeth King, writing in The Atlantic magazine in 2017, points out that today “tomboy” can be a sexist, racist and gender-bending term and it is “fair to wonder whether adults should refer to nontraditional girls as ‘tomboys’.” There is no such confusion with the word cowgirls. They are girls.

A problem: skirts

According to Wyoming writer Teresa Jordan, in her 1962 book “Cowgirls, Women of the West,” the first western women were portrayed as a “prairie Madonna, with long calico skirts and a babe in each arm.” This mythical ranch woman might have tended a garden along with all the household and child-rearing chores, but the men did the real ranch work. Zane Gray and other writers of western fiction sometimes perpetuated this myth, as did myriads of western movies. Frontier women could be schoolteachers or ranch wives, but cowgirls were a highly unusual plot twist.

But the fact was that unless there were plenty of hired hands, there were times when everyone on a ranch had to pitch in to move cattle, mend fences and other necessary outdoor chores, often on horseback. If there were no boys in the family old enough, the girls were pressed into service or happily volunteered. There was a problem to surmount in the early days, however—the skirts.

“I doubt that my grandmother on the Williams side ever wore pants,” remembers Laramie ranch woman Dixie Mathison, talking about her grandmother Minnie Williams of the Chimney Rock Ranch in Albany County in the early 1900s. “My mom, Gussie Norell Williams, wore pants, but that was in the 1940s,” says Mathison. “A lot of women that worked outside all the time wore men’s trousers; there are things you can do in pants that you can’t do in a dress.”

The boy’s or men’s trousers were a problem for girls, they just didn’t fit right. My girlhood friend, Claire Bame Kirsner of Toledo Ohio, remembers that the stable where she worked as a youngster demanded that she wear pants in the 1940s. “The boy’s pants got all bunched up and were so uncomfortable,” she recalled, “but there weren’t any pants to be had for girls then.”

A woman Teresa Jordan interviewed for her book remembers that the first riding outfit she had was a divided skirt, which was so loose at the hem that it flapped around as she was riding and frightened the horse. “We had to tie it down with twine or rawhide until the horse got used to it,” said Marie Bell, the author’s great aunt, from Iron Mountain, Wyoming.

Sidesaddles were the ladylike gear for women before 1900, and I am told that every western museum has a sidesaddle in perfect condition because the women never used them, preferring to sit astride. The Laramie Plains Museum has several fitting that description. The museum also holds 1890s riding outfits of heavy corduroy or velvet material with real trousers covered by a side-split skirt at front and back. Thus the woman would not be seen to be wearing trousers when dismounted. They weighed a lot and probably frightened the horse, but grandmothers would have approved, perhaps.

Pushing aside the myth

Annie Oakley, whose real name was Phoebe Ann Moses Butler, performed with Buffalo Bill’s Wild West and Congress of Rough Riders of the World” from 1885 to 1901. The first celebrity cowgirl, it was her prowess with a rifle that brought her fame as “Little Sure Shot.”

There were other young women who performed in similar Wild West shows and achieved some fame, but one of the most charming was a trick rider, Prairie Rose Henderson. She is reported to have been a Wyoming native, born as Ann Robbins at a vague time in the 1870s or 1880s, though so far I haven’t been able to verify much.

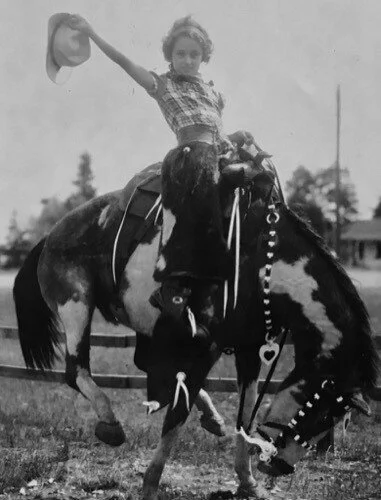

“Prairie Rose” came to fame as a winner in the first Cheyenne Frontier Days celebration of 1899. She applied to compete in bronc riding, the first female to do so, and won. In 1911 she was awarded the title World Champion Bronc Rider, and in 2008 was inducted into the Cowgirl Hall of Fame in Ft. Worth, according to Sen. John Barrasso’s blog, touting her as an example of Wyoming’s famous natives.

There weren’t good outfits for women to wear, so Prairie Rose designed and made her own, which were fairly sensational for 1899. Her tall cowboy boots, complete with spurs, covered up most of her legs, and the knee-length bloomers she designed were unique, to say the least. In 1899, nearly all women were wearing skirts only an inch or two above the floor. Annie Oakley performed in a corseted dress that ended just below the knees, but was photographed in floor length dresses when not performing.

A few years ago I showed a mystery photo of a happy cowgirl to the late Amy Lawrence of Mandel Lane west of Laramie, hoping that this genuine cowgirl and Jubilee Days Queen of 1942 might be able to identify the woman in the photo for the museum’s records. She sputtered that “no respectable western girl would be caught dead in that get-up—that’s a picture of a trick rider!” Did that mean she couldn’t be a real cowgirl? The mystery woman later turned out to be Prairie Rose Henderson.

Is the horse essential?

I asked a few other people what the word cowgirl conjures up and got some highly varied answers. My fellow octogenarian friend, Margaret, says she never considered herself a cowgirl because she was born on a farm, not a ranch, and the farm was “east of the Missouri River, not west river,” of South Dakota, where the cowgirls were from. This, despite the fact that until 2019 when her most recent horse died Margaret nearly always had a horse in her life.

I touched base with my Toledo friend, Claire, who portrayed a cowgirl in 1945 when we were pictured as five-year-olds on our first Halloween outing. I still have that snapshot of us. I moved away from Ohio in 1950, so Claire and I had not spoken in 70 years when she called to answer my emailed questions. I wondered who her role model was back then.

“I can’t remember any,” said she about the role model; it was way too early for Dale Evans, who didn’t even marry Roy Rogers, her fourth husband, until 1947. Claire doesn’t consider

herself a cowgirl either, though she was born to be a horsewoman, much to the confusion of her parents, a town-dwelling dentist and family. She says she has never actually owned a horse but worked in a stable for free riding lessons starting very early, and ended up showing horses for wealthy stable owners until very recently when knee replacement surgeries convinced her that it was time to hang up the reins. But she did small saddle Eastern Style riding or “horse jumping” as some westerners call that, which does almost disqualify you from belonging to the sisterhood of cowgirls.

Are cows essential?

One person I talked to said a cowgirl has to be comfortable around cows. The local all-around role model in that category for many is Shirley Wright Lilly. Ranch historian Dicksie Knight May quizzed a number of people about their definition of a cowgirl, and like mine, her results showed that “Shirley Lilly came up first on the list.” Shirley was Jubilee Days Queen in 1951 and became the wife of ranch manager Frank Lilly the following year.

From what people say about Shirley, it sounds like whatever Frank and the hired hands could do, Shirley could do. She told me a while back that once they were driving cattle in a blizzard from the Chimney Rock ranch to Tie Siding for shipment (a good 20 miles). She had to find a fence post to hang onto to dismount when they finally arrived, because her protective gear was frozen too stiff to bend.

After herding cows at branding time, if meals for a huge crew of neighbors and volunteers had to be prepared, Shirley could do that too. Maybe girls who grew up on sheep ranches could be called cowgirls, but I didn’t find any in my small sample to quiz on that point, or to rival the accomplishments of Shirley, who continues to be a driving force to see that Jubilee Days stays on track for next year.

So who is a cowgirl?

There are several museums with the name Cowgirl in their title—the National Cowgirl Museum and Hall of Fame in Fort Worth is one, and there is a much smaller free museum in downtown Cheyenne—the Cowgirls of the West Museum & Emporium. Run by volunteers, the latter is closed for summer 2020. There aren’t any for tomboys, but being called a real cowgirl is a great compliment.

It seems clear that today’s cowgirls don’t have to have come from a ranch or have a horse or cows. Most probably have day jobs that might be far from the ranch as waitresses, hairdressers, teachers or bankers, but they master the special attitude that marks a cowgirl.

The attitude includes a spunkiness that allows them to feel confidant about competing on an equal basis with men and proving that “gals have true grit” also. That self-assured look is on the face of Prairie Rose Henderson. Thanks to the help of Dicksie May Knight, the riddle of who she was has been partially solved, though it would be nice to know more about this spunky Wyoming gal of 100 years ago.

By Judy Knight

Source: Laramie Plains Museum

Caption: Prairie Rose Henderson, Champion Bronc rider at the first Cheyenne Frontier Days contest in 1899, and a famed trick rider. The chin strap on her cowboy hat was a clue to her identity as a performer in this undated newspaper clipping that had no caption when it was given to the Laramie Plains Museum. The brand inserted at the bottom of the photo is still a mystery

Source: Claire Bame Kirsner

Caption: Claire Bame on horseback in full cowgirl regalia, though she never considered herself one. The horse, unfortunately, was the product of taxidermy discovered at a touristy spot on a family vacation at Mackinac Island, Michigan in the mid-1950s.

Source: Judy Eddy Knight

Caption: Best friends Claire Bame (cowgirl) and the author as a Dutch girl, in Toledo, Ohio, 1945, practicing how to say “trick or treat.” It was our first Halloween, when we were five and in the first grade. Neither costume made the list of top sellers for Halloween 2019 according to one website. What will 2020 bring? Masks, for sure!